What follows is an essay by Thomas E. Wartenberg (Mount Holyoke College), based on his recent book Thoughtful Images (OUP, 2023).

The first illustration of philosophy that I have been able to identify is the Roman mosaic from Pompeii made in the first century C.E. that you see here. It shows a group of men focused on a standing man who is speaking. The figures have been identified as Plato holding a stick and pointing, surrounded by other philosophers from Ancient Greece, though there is debate about who they are.

This beautiful mosaic illustrates an aspect of the Platonic practice of philosophy: it depicts a group of men having a discussion. This is an important aspect of how philosophy was done in Ancient Greece, and it accords with the famous portrait of Socrates doing philosophy with his followers. It thus represents an advance in the illustration of philosophy, for the only traces of philosophy in previous works of art were the busts of famous philosophers.

One question this lovely work poses is what other aspects of philosophy can be illustrated. After all, philosophy poses very abstract questions and its proposed answers lack the concreteness typical of works of visual art. Given these facts, it might seem paradoxical to say that philosophy itself rather than its practitioners and modes of practice can be presented in a work of visual art.

An account of how philosophical texts, concepts, and theories can be illustrated in visual art begins with the realization that philosophical texts are not as abstract as might be thought. The texts that constitute the Western history of philosophy are replete with literary images of various types, so let’s turn to these first to understand how philosophy can be illustrated.

Illustrating Thought Experiments

One common feature of philosophical texts that almost calls for visual illustration is the thought experiment. A thought experiment presents an imaginary scenario that readers of the text are supposed to imagine. Thought experiments come with instructions that help readers understand their point. The scenario and the instructions are equally important components of a philosophical thought experiment.

We can find examples in Plato’s dialogue the Republic, a text studded with thought experiments. Early in the first book, to show the inadequacy of a proposed definition of justice as giving people what they are owed, Socrates asks his interlocuters to consider a weapon that they have borrowed from a man. Suppose, Socrates continues, that the man has suffered a breakdown and now would pose a risk were the weapon returned to him. Would it still be just to do so as the proposed definition suggests?

Because Socrates’ interlocuters—as well as readers of the dialogue—have the intuition that they should not return the weapon to the person who has suffered a breakdown, it becomes apparent that the proposed definition is inadequate. Socrates has presented a counterexample to the proposed definition in the form of a thought experiment.

The Republic has a number of more elaborate thought experiments. One of them, the Parable of the Cave, is especially important to our discussion because artists have illustrated it consistently down through the ages. Plato presents this parable in order to, among other things, explain the nature of his metaphysics according to which the objects we normally take to be real—such as tables and chairs, trees and grass—are merely “appearances” of a more fundamental reality, the Forms. One reason why Plato holds that ordinary things cannot be the ultimate reality is that they are constantly changing. Tables and chairs break and fall apart; trees and grass wither and die. Because they are subject to decay, such things cannot be fully real.

In contrast, Plato holds that the Forms never change and are what they are eternally. A man who is handsome will lose that trait as he ages, but handsomeness itself—the standard by which we judge the man to be handsome in the first place—does not change. It simply applies to different things at different times.

Here is the scenario presented in the Parable of the Cave: There’s an underground cave lit only by a fire. In front of the fire is a group of people who are bound from head to toe so that they can only see the wall of the cave in front of them. On the wall of the cave a series of shadows are cast by the fire as objects are paraded in front of it. The prisoners can only see these shadows, which they take to be real things.

Although there is more to the Parable than this, what I have just summarized is sufficient for my purposes, for it is this scene that some of the illustrations of the Cave depict. This is the case with the first illustration of it that I know of it, a painting attributed to Michiel Coxcie (1499-1592), La Grotte de Platon (16th century).

How exactly does this painting illustrate the Parable of the Cave? Two concepts I introduce in Thoughtful Images will help answer this question. They are fidelity and felicity and both are central features of illustrations of texts. To exhibit fidelity, an image must be faithful to the text it aims to illustrate, that is, include visual features corresponding to the linguistic description. We can see many features of Coxcie’s painting embody fidelity. The people in the picture are chained, indicating that, as Plato specifies, they are prisoners. On the wall behind the prisoners, a central flame shines light across a few objects (atop the pillars) and casts shadows of those objects (and the pillars) down the concave wall behind the prisoners. All of these features exhibit fidelity to Plato’s text.

Some features of the painting, however, sacrifice fidelity for felicity. An illustration that is felicitous contributes to the integrity of the work in its new medium. So, although the placement of the prisoners mostly reclining on couches in a circle in states of semi-nudity departs from Plato’s description, it satisfies norms for paintings that were prevalent in the sixteenth century when the painting was created and helps make the painting a work of art in its own right.

An interesting feature of the painting is the presence of the two fully clothed figures at the top of the circle of prisoners. They stand out from the partially nude prisoners but their role is not clear. The one on the right appears to have two chains across his chest, marking him as a prisoner, though it is unclear why he is fully clothed and his calm demeanor distinguishes him from the others. The fully clothed figure on the left seems to be looking carefully at the images on the cave’s wall and thus represents the idea that the prisoners are deluded about the nature of reality by their observation of shadows rather than real things. Although the color of the robes of these two figures adds to the visual impact of the painting, the rationale for their appearance remains unclear.

La Grotte de Platon demonstrates the importance of fidelity and felicity in illustrations. These conflicting norms result in the creation of artworks that are both faithful to and different from the text they illustrate, with their departures making for a work that has more integrity in its new artistic medium.

Illustrating Wittgenstein

Thought experiments are not the only aspects of philosophical texts that have been illustrated by artists. Several well-known conceptual artists have, for example, illustrated passages from the work of Ludwig Wittgenstein. Wittgenstein’s texts are often obscure and difficult to interpret. For this reason, illustrations of them are welcome. Illustrations shed light on the works they illustrate, helping viewers understand the often difficult and abstract ideas of philosophy.

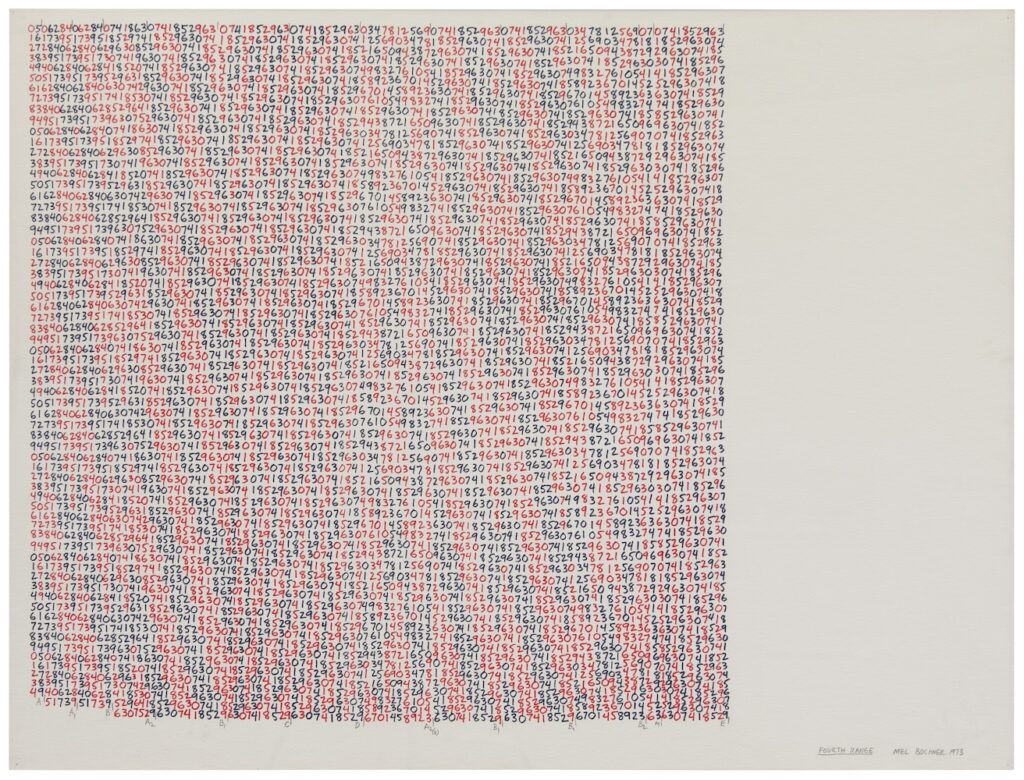

Here is a drawing by the contemporary artist Mel Bochner (1940– ), who is often characterized as a conceptual artist. Fourth Range (1973) illustrates a claim made by Wittgenstein in his posthumously published book, On Certainty (1969).

In On Certainty, Wittgenstein targets the philosophical theory of skepticism, the view that human beings do not possess knowledge, beliefs whose truth is certain or indubitable. This theory can be traced back at least to René Descartes who maintained in his Meditations on First Philosophy (1641) that it was possible to doubt the truth of every one of his beliefs, and in so doing discovering that nothing is certain. (He goes on to identify one belief that is immune to doubt in his famous Cogito ergo sum, but we can ignore that for our purposes.) This thesis of Descartes’ is the result of what is termed “hyperbolic doubt,” a doubt that extends to all of one’s beliefs.

Wittgenstein, on the contrary, maintains that hyperbolic doubt is not genuinely possible. He maintains that doubt always occurs in a specific context. More specifically, he argues that doubts—or errors which lie at their basis—can only arise when a rule has been violated. We can doubt the veracity of the statement “2+2=5” because we know that 2+2=4 according to the rules of arithmetic. We recognize that asserting “2+2=5” is a mistake because it violates those rules.

Despite this intuitive example, Wittgenstein’s argument is difficult to follow and understand. We still might be unsure why a rule is necessary to identify a mistake. Although Wittgenstein attempts to clarify the reason for this, readers may be uncertain about his reasoning. And that’s where Bochner’s illustration becomes helpful. But for it to assist readers in understanding Wittgenstein’s argument, they have to observe the drawing very carefully. (I will give a quick interpretation of it here. For a more extended analysis, see Thoughtful Images, chapter 8.)

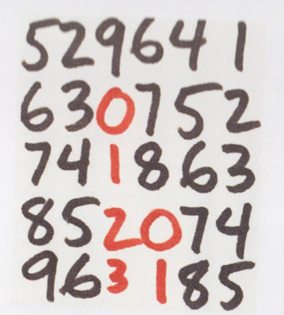

Viewers can see the patterns of ‘V’s and ‘W’s when looking at the work as a whole, but they also need to focus on its details if they are to understand how it illustrates Wittgenstein’s claim. Notice the following features of the work: It is composed of repeated sequences of the numerals ‘0’ through ‘9’ in numerical order. These numeric sequences, written vertically, alternate between red and black. At the end of each column, the sequence continues in the next column to the right without a break in the numerals, although it can start at the top or the bottom, depending, and the color of the sequence can change at this point though it need not. Each ten columns form what I call a “block.” In a block, the following rules remain constant: those that specify the length of a column, those specifying whether the sequence will continue at the bottom or top of the next column, and finally those specifying whether the color of that sequence will remain the same or change. However, these rules will vary from one block to the next, a fact indicated by letters at the bottom of the block—A, A1, B, etc.—that indicate the presence of a specific set of rules.

In following the sequences of numerals, the especially attentive viewer will notice that a mistake occurs in the fifth column of the fourth block when a black sequence ends with an ‘8’ rather than a ‘9.’ Viewers recognize this as a mistake because they realize it violates the rules by means of which the drawing has been created. Only because viewers have seen the presence of the rules are they able to identify the move from a black ‘8’ to a red ‘0’ as a mistake.

Bochner’s drawing thus illustrates Wittgenstein’s contention that it is the presence of a rule that is required to recognize that a mistake has been made. And this helps make viewers grasp the rationale for Wittgenstein’s claim. Bochner succeeds because he has invented a “numbers game,” an analogue to Wittgenstein’s notion of a language game, whose rules I have just explained. This “illustration” of Wittgenstein’s claims about language and knowledge is an innovative way to demonstrate the truth of the philosopher’s view.

Plato and Wittgenstein are among the philosophers whose works have been illustrated most often by artists. As we have seen, Plato’s theories were illustrated by artists beginning in the 16th century. But the interest did not end there. Artists have found Plato’s philosophy a suitable subject for illustration throughout the ages, even into the 20th and 21st centuries. The famous conceptual artist Joseph Kosuth produced both an installation, One and Three Chairs (1965), that illustrates and critiques Plato’s philosophy and a neon work that illustrates another one of the thought experiments in the Republic, viz the Divided line, by literally replicating a portion of Plato’s text in bright white neon tubing. The latter was included in a 2018 exhibition at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles entitled Plato in L.A. that featured works by 11 artists inspired by Plato.

The reason for artists’ interest in Plato is obvious. Because so many of his philosophical texts have come down to us in their complete form, Plato exerted a tremendous influence on Western thought, an influence that extended to art. The vividness of the literary images in his work, including not only the Allegory of the Cave but also the Divided Line, practically cry out for visual renditions. (His student Aristotle was also very influential, and many artists have illustrated his writings, as I discuss in chapter 3 of Thoughtful Images.)

Wittgenstein has also fascinated artists. Conceptual artists were particularly interested in his work and depicted his ideas in innovative ways. As he did with Plato, Kosuth created pieces such as 276. (On Color Blue) that illustrated Wittgenstein’s ideas by rendering his words in neon. Bruce Nauman also included Wittgenstein’s words in A Rose Has No Teeth which reproduces in a lead plaque a remark of Wittgenstein’s from the Philosophical Investigations (¶314). Jasper Johns included a drawing of the duck-rabbit, a famous drawing Wittgenstein included in the Investigations, in Seasons: Spring (1987), a work that includes other allusions to Wittgenstein’s discussion of aspect seeing in the Investigations. Both Eduard Paolozzi and Bochner made a series of prints that illustrated other claims made by Wittgenstein, and Maria Bussmann’s drawings included illustrations of Wittgenstein’s early book, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921). (For more on this, see Thoughtful Images, chapters 7 and 8.)

Why did Wittgenstein exert such a powerful influence on artists in the second half of the twentieth century? One factor was the importance attributed to language by both artists and philosophers in the 20th century. Wittgenstein’s views were one of the central reasons for this shift in philosophical interest away from the nature of the mind and its ideas and onto language as the vehicle for expressing those ideas. Conceptual artists shared an interest in language and therefore naturally gravitated to Wittgenstein because of this shared concern.

Wittgenstein’s aphoristic writing style also enabled artists to employ language-based illustrations of his works. It would be hard to extract a suitable quotation from, say, the writings of Kant to display in a work of art, with the possible exception of his famous statement that two things inspired him with awe, the starry heavens above and the moral law within. But with Wittgenstein, as the examples of Kosuth, Nauman, and Bochner attest, it was easy to find quotations worthy of display in an artwork.

And then there was the figure of Wittgenstein himself. His revolutionary ideas and seriousness of purpose inspired a coterie of followers who took him to be a latter-day Socrates, the only other secular figure in the history of European philosophy to exert such a personalized influence. Like Socrates, Wittgenstein attracted disciples not just for his philosophical views but also for the single-mindedness with which he pursued his philosophical investigations. Norman Malcolm’s Ludwig Wittgenstein: A Memoir presents a vivid picture of this inspirational philosopher. Paolozzi’s As Is When: A series of screenprints inspired by the life and writings of Ludwig Wittgenstein (1964-65) attests to the attraction that Wittgenstein’s life exerted on artists.

The examples of Plato and Wittgenstein show how significant philosophical theories are for many artists. There are many reasons why artists choose to illustrate philosophical texts, ideas, and theories. Among them might be a desire by artists to show that art can be the equal of written texts as a vehicle for the transmission of philosophical ideas despite the latter often being taken to be the primary source for philosophical ideas. The artists who have illustrated philosophical ideas have not done so slavishly, as if art could only be the handmaiden of philosophy. Rather, works of art that illustrate philosophy are inventive in their presentation of abstract philosophical ideas in concrete visual form even as they attest to the importance of written philosophy as a source of artistic inspiration.

Thomas E. Wartenberg is the author of Thinking on Screen: Film as Philosophy (Routledge) and Big Ideas for Little Kids: Teaching Philosophy Through Children’s Literature, among other works. He is Professor of Philosophy Emeritus at Mount Holyoke College.

September 7, 2023 at 1:38 pm

I appreciate this provocative and succinct introduction to the book, which I hope at some point to read (and look at)! The following is from the end of the Preface by Professor Wartenberg:

“The subtitle of the study, Illustrating Philosophy Through Art suggests that it will be a comprehensive examination of how philosophy has been transformed into art. This is misleading in that both the works of art and the philosophical theories that will be considered belong exclusively to the Western tradition. There are, of course, traditions of philosophy other than the Western one, including those find in China, India, and Africa. I have not included illustrations of philosophy in such traditions primarily because of my own ignorance. I do not know enough about those traditions—either philosophical or artistic—for it to make sense for me to have attempted to include them in this study. I can only hope that others more conversant in those traditions will be inspired by this book to investigate how those philosophical traditions have been illustrated.”

I very much appreciate this qualification and acknowledgment of non-Western philosophies, although the publisher might have made this more explicit to the potential reader by simply having the subtitle read “Illustrating [Western] Philosophy Through Art.” In any case, it should be pointed out there there are indeed sundry connections between non-Western philosophies and their art traditions as several works by the late Andanda K. Coomaraswamy amply attest (and Tibetan Buddhist art in particular is exemplary in this regard). Here is but a small (and not necessarily representative) sample by way off a brief taste of the available literature:

• Diagne, Souleymane Bachir (Chike Jeffers, trans.) African Art as Philosophy: Senghor, Bergson, and the Idea of Negritude (Seagull Books, 2011).

• Jullien, Franҫois (Paula M. Varsano, trans.) In Praise of Blandness: Proceeding from Chinese Thought and Aesthetics (Zone Books, 2004).

• Jullien, Franҫois (Jane Marie Todd, trans.) The Great Image Has No Form, or On the Nonobject through Painting (University of Chicago Press, 2009).

• Lippit, Yukio. Japanese Zen Buddhism and the Impossible Painting (The Getty Research Institute, 2017).

• Thompson, Robert Farris. Flash of the Spirit: African & Afro-American Art & Philosophy (Random House, 1983).

• Winfield, Paula J. Icons and Iconoclasm in Japanese Buddhism: Kūkai and Dōgen on the Art of Enlightenment (Oxford University Press, 2013).