What follows is a guest post by Nicholas Whittaker, PhD candidate in philosophy at CUNY Graduate Center.

I.

Recently, Prince Harry and Meghan Markle sat down for an interview with Oprah Winfrey, where the three discussed the racism Markle experienced from the U.K. royal family. Immediately after, screengrabs of Harry, Markle, and Winfrey exploded across social media as (frankly, really good) memes. Days later, the images of Harry and Markle had lessened in circulation, but Winfrey’s were just picking up steam. More and more memes emerged focusing solely on her dramatic facial expressions, like:

Was this uneven distribution a mere accident, or a side effect of Winfrey’s megacelebrity? Perhaps; but there’s a more sinister possibility. The Winfrey memeing has reignited a debate around the concept of digital blackface. Digital blackface is, in short, “the act of inhabiting a black persona” in virtual digital space. A prime example is memeing: white and nonblack people fervently making and sharing memes of black people. This act, Lauren Jackson argues, is only the latest of an undeniable historical tradition of blackface, where this refers not only to the literal donning of shoeshine but the various ways in which “black” performance – “black” ways of speaking, looking, or doing – is seized by nonblack performers.

I agree with Jackson, and others, that digital blackface is troubling. But I’m also troubled by certain assumptions people often make when explaining why. I want to dispel those assumptions, and hopefully make clear that we don’t need them to understand and condemn digital blackface.

II.

Frequently, the problem of digital blackface is articulated in this way: “Digital blackface is what happens when non-black people pretend to be something they’re not – black – by performing certain traits or attitudes that aren’t ‘theirs’ to perform. This is appropriation, and it’s wrong.” Examples of this way of thinking abound (even when other, better arguments are also utilized, like in Jackson’s fantastic work on the subject). I think this way of framing the problem is potentially really dangerous, and makes it hard to see what the problem actually is.

There are lots of ways of understanding appropriation, and what makes it wrong. In general, I’ve found that the way it’s articulated when it comes to digital blackface often amounts to what is called “cultural nationalism” about blackness. Cultural nationalism is the belief that there are certain aesthetic ways of presenting and behaving that are distinctly black and should remain distinctly black. In this case, then, the ways of performing and behaving these memes demonstrate should be reserved for black people.

One way that people explain cultural nationalism is by making a dichotomy between “who one really is” and “how one is presenting.” Imagine a certain cultural practice – say, wearing kente cloth. Then imagine a black person and a white person each wearing kente. What, if anything, makes it ok for the black person to do so, and very much not ok for the white person to! One way to explain it is to say that the white person is “pretending to be something they’re not”; they’re acting in a way that’s different than who they “really are.”

This sort of explanation is often used to condemn digital blackface. In sharing or making a given meme, nonblack people are “pretending to be black.” But this is, at least in the case of memes (as opposed to, say, kente), dangerous. What this argument seems to suggest is that certain people behave a certain way – talk loudly, or move a certain way – because of some intrinsic fact about them, some “essence” they have. But as many, many black theorists have argued, this claim gets dangerously close to the clearly racist belief that certain human beings act a certain way just because of “who they really are”.

This point is beautifully made by the following extended passage from bell hooks’ Art on My Mind:

Black people comprise half the population of the small midwestern town that I have lived in for the past six years, even though the neighborhood where my house is remains predominantly white. Cooking in my kitchen one recent afternoon, I was captivated by the lovely vernacular sounds of black schoolchildren walking by. When I went to the window to watch them, I saw no black children, only white children. They were not children from a materially-privileged background. They attend a public school in which black children constitute a majority. The mannerisms, the style, even the voices of these white children had come to resemble their black peers – not through any chic acts of cultural appropriation, not through any willed desire to ‘eat the other’. They were just there in the same space sharing life – becoming together, forming themselves in relation to one another, to what seemed most real. This is just one of the many everyday encounters with cultural difference, with racial identity, that remind me of how constructed this all can be, that there is really nothing inherent or ‘essential’ that allows us to claim in an absolute way any heritage.

What this moment reveals is that the dichotomy between “how one presents” and “who one really is” is not ironclad. We cannot always, or maybe even often, unglue the black performance of digital blackface from its nonblack practitioners, not for moral reasons but because it simply does not make sense to do so. These boys do not have some “core” of whiteness that they really are; the aesthetic markers we feel inclined to call “blackness” aren’t a costume covering up some truth. It simply is not useful or accurate to call memes of black people “disguises” white people use to cloak their “true selves.” We live in a global, digital economy, in which circulated aesthetic styles and performances – like memes – make us who and what we are. “Digital blackface” is no exception.

It’s very, very important that, as Paul Taylor has recently beautifully sketched, we remember that this love or embrace of black ways of life is often deeply interwoven with a disgust and fear of black people. Talking a certain way, dressing a certain way, behaving a certain way does not prove that one is not themselves contributing to or invested in antiblackness. So it might be the case there are real reasons to be suspicious of, and even condemn, nonblack people who “act black.” But that’s different than being suspicious of, and condemning, nonblack people because they’re “not being who they really are,” or they’re being “inauthentic.”

When it comes to digital blackface, it is simply misguided to build our critique off of ideas about racial and cultural essences, off of ideas about “who people really are.” And, even more importantly, we don’t even need such ideas to explain what makes this practice so wrong!

III.

A crucial concept for contemporary black studies and philosophy is the notion of fungibility. Powerfully introduced by Hortense Spillers, fungibility tries to capture the way in which black people are reduced, in an antiblack world, to commodities. In slavery, Spillers argues, black bodies were stripped of all the features we typically assume human beings have – name, culture, family, consciousness, liberty, rights, and crucially individuality. They became mere items on a ledger, reduced to how much they cost. This reduction is what made slavery possible; only by being reduced to pure, inhuman matter could these bodies be bought and sold in a way that didn’t challenge the liberal humanistic values their Enlightenment captors subscribed to. To be fungible is to be able to be bought and sold, exchanged, as though one were merely a product, exactly the same as every other product of the same kind.

Spillers and, especially forcefully, Saidiya Hartman have argued that this fungibility did not disappear when slavery did. We live in what Hartman calls “the afterlives of slavery,” and much of what was true then is true now. A prime example often pointed to is that of images of black death and the black dead. These images – of George Floyd, of Breonna Taylor, of Tony McDade – and, worse, the videos of the their murder, the brutal beating of black children, etc., are heavily circulated through social media and news reports. This repetition, these theorists argue, is an aestheticization of the spectacular violence that defines antiblackness. There’s much to say here; the point for the present is that this circulation reduces the human character of what’s portrayed into fodder for clicks, likes, and views. These images are not employed for the sake of a radical politics or emotional affiliation, but as products in service of the pursuit of profit.

The point of this complicated tangent is that digital blackface might be seen as an instance of fungibility. The circulation of Oprah throwing up her hands, or the rapper Conceited pursing his lips, reduces complex human beings into flat images; the human being disappears. The image then becomes a blank slate that can be projected upon. Take, for example, the way the recent Oprah memes transformed from representations of disgust with racism to representations of phenomena as varied as discomfort at playing baseball, characters from the Marvel Cinematic Universe, and shock upon hearing the deconstructive philosophies of Michel Foucault. Who Oprah is, as a human being, no longer matters. She has become pure matter, or a paper doll (as Frantz Fanon writes, “The Negro is a toy in the white man’s hand”), to be molded into whatever its owners desire.

I think fungibility is crucial to explaining what’s wrong with digital blackface. I’m drawn to it precisely because it sidesteps the cultural nationalism debate. The use of fungibility is not an investment in debates about authentic aesthetic performance and consumption. But to get to the crux of such a critique, we have to make a crucial clarification.

Fungibility reveals the ways in which the black persons that memes capture are being “annihilated”, so to speak; the meme is reducing away their personhood so they can be endlessly circulated and projected upon. So one might understandably say that this is the source of the evil, the antiblackness, in digital blackface. However, this is unsatisfactory: because such a reduction or annihilation is the nature of memes. All memes are fungible.

I’m not saying that nonblack images or people are fungible in the way black images or people are all the time. In most cases, I agree that black people are uniquely fungible. But I’m suggesting that memes are a bizarre special case; the meme is a particularly odd aesthetic phenomenon built on fungibility. Memes are underdetermined, by which I mean they open themselves up to a vast multiplicity of meanings. Thousands, perhaps more, versions of the popular “cheating boyfriend” meme exist, all with different emotional registers projected upon them. The gif of Jack Nicholson nodding has been used in a vast multiplicity of possible contexts. It’s this multiplicity that allows memes to be circulated to such an unprecedented extent. Memes are blank slates; they exist to be projected upon.

Sheer fungibility, then, is not enough to explain what makes digital blackface feel wrong. It misses out on what makes memes so distinct. Realizing that allows us to develop, I think, a more precise challenge (and to see that maybe there are ways, when it comes to memes, for fungibility to be ok!). Is fungibility useless (for this and only this specific case), then? Absolutely not. Fungibility isn’t, by itself, why and when digital blackface goes wrong; but it explains how it does go wrong. Leila Taylor, in her book Darkly: Black History and America’s Gothic Soul , gives us a brilliant example for seeing how.

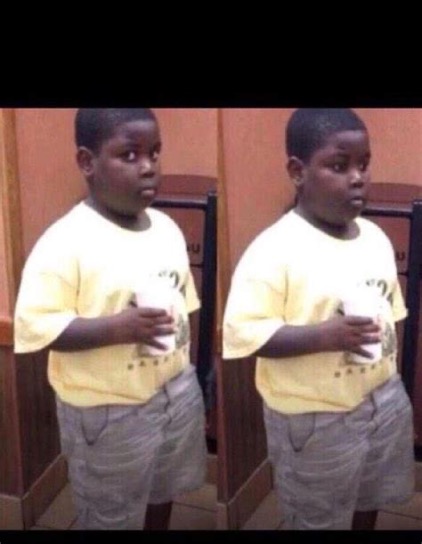

Taylor examines the following meme: a young black boy, eyes wide open (or shifting to the side, depending on the version).

Taylor argues, quite convincingly, that a certain base meaning has accrued to this image: the boy is taken to represent a kind of disaffected cool coming face to face within something decidedly weird or uncool. One might say the meme captures the sentiment “That’s none of my business.” Taylor emphasizes that this meaning is often racialized. As a prime example, she examines a popular meme in which the boy is juxtaposed with a video in which a group of white cybergoths dance under a bridge. The juxtaposition, Taylor argues, takes on a certain aesthetic character: the boy is weirded out by the bizarre, effusive dorkishness of the cybergoths. And this “weirded” out has a racial character: specifically, the boy is weirded out by what one might call “that white people shit.”

In being so constructed, Taylor argues, the meme creates a certain racial heuristic or cliche; the boy’s blackness is figured as cool, where cool is directly contrasted with a kind of excessive emotional expression, a flamboyance that Taylor spends her book arguing the cybergoths, and goths, emos, and scene kids in general, exemplify.

Taylor’s brilliant realization (my jaw dropped when I first read this) is that this is actually an explicit manipulation of the original meme of the boy. The image of the boy as circulated is a cropped image; the original photo reveals him standing behind a young girl that, Taylor suggests, he has a crush on.

When one looks at the full image, the boy’s face, his posture, what he meant, is radically changed. “That white people shit is weird” becomes juvenile nervousness, an effusiveness of awkward intimacy; pure, gushy feeling, which is precisely what the juxtaposition with the cybergoths implies the boy does not have.

A great deal of theoretical work has been done on the covering up of black male intimacy and emotion; Taylor reveals that this meme is a case of that covering up. The meme is, as Jackson puts it, a stereotype, a cliche; it is a specific way of understanding what possibilities black life holds. A certain possibility – pure, gushy feeling – is covered up, while another – disaffected cool – is highlighted. Instead of being underdetermined, the image of the boy is overdetermined; it is manipulated so that it is actively and discretely read a certain way.

This is digital blackface. The problem isn’t that nonblack people are “pretending to be us,” or that black people are being reduced to fungible. Digital blackface is actively skewing our perception of what blackness contains, and thus what possibilities are open to all of us, regardless of phenotype (if, that is, I and hooks are right). Importantly, though, this is possible because memes are underdetermined and fungible; it is because memes in general are open to this kind of manipulation and projection that a distinctly antiblack manipulation and projection can happen.

When we realize that we can condemn this manipulation without either a) buying into cultural nationalism or b) condemning fungible memes as inherently antiblack, I think we avoid some dangerous pitfalls. Crucially, we avoid the notion that the problem of digital blackface would be fixed if nonblack people “stopped doing black things,” or if black people got “ownership” of our images once more through the end of fungible memeing. I think these pitfalls are unfortunately common in conversations about not just digital blackface, but appropriation in general, and it’s important to see that they might do more harm than good.

I think avoiding those two bad starting points also sets us up for more than just critique. When we see that memeing – even memeing black people, and even when nonblack people participate in such memeing – is not inherently antiblack, we allow ourselves to ask: what would – as silly as it may sound – a generative, radical, socially connective, powerfully black memeing practice look like? I’m not quite sure, truth be told, but I’d like to find out.

Editorial note: The author prefers to leave “black” uncapitalized, in order to resist the notion that ‘blackness’ is a coherent, discrete, and sovereign Identity.

Nicholas Whittaker (@nwhittaker10) is a PhD candidate at CUNY Graduate Center. They work primarily at the intersection between continental phenomenology, philosophy of art, and black studies. Their forthcoming publications include essays on the work of Adrian Piper, aesthetic experience, “black duplicity,” and abolitionism in popular culture.

Edited by C. Thi Nguyen

April 15, 2021 at 5:19 am

Interesting post! I was totally persuaded that the problem isn’t about pretending to be someone you’re not.

It sounds like, in your view, the real objection to digital blackface is basically a consequentialist one: it causes people to have misleading impressions of what black people are like. As you put it: the use of these memes is “actively skewing our perception of what blackness contains.”

I had a few questions about this.

First, if the problem is just about the content of the memes not the person who’s posting them, wouldn’t it be equally bad for *anyone* to post them, regardless of race?

Second, how broadly does this account apply? I don’t yet see how the Oprah memes (for example) are skewing anyone’s perceptions of black people. They seem to accurately represent what Oprah is like, rather than concealing some context, as in the other meme.

Finally, I was wondering if there might still be something more to the fungibility worry. I’d be a little weirded out by a white person who only used reaction gifs with black people, even if the gifs weren’t full of stereotypes. My hunch is that it reveals a kind of racist attitude—finding black people “amusing.” Kind of like how some white people do “impressions” of black English because they think it sounds funny. That kind of thing strikes me as bad in a sort of deontological way; it shows a lack of respect, an unwillingness to take other people seriously.

April 15, 2021 at 2:37 pm

Why make a career out of finding more ways to claim to be a victim? My guess if people were NOT sharing memes of black people, you’d say that was a problem, too.

April 16, 2021 at 12:29 am

Fascinating that digital blackface is criticized, like Orientalism, and other forms of difference fetishism. But there’s one exception, isn’t there? https://nplusonemag.com/issue-30/essays/on-liking-women/

April 16, 2021 at 1:54 am

Greg: I don’t think that kind of comment is very helpful. If someone gives you a rational argument, you owe it to them to respond with reasons—not baseless guesses about their motives, or about what they might be saying in other possible worlds.

April 17, 2021 at 2:30 pm

I think what Greg was saying: The current fad in Academia and Media, of searching for more & more things to label “micro-aggressions”, will not create a harmonious society. Continually stoking racial grievances and cultivating humorlessness will have the opposite effect of what we want. It creates an environment where everyone has a chip on his shoulder, everyone is preoccupied with perceived affronts to his own dignity, and no one feels free to be at ease or natural around other people. Lighten up, Man.

And I too am “weirded out” by those “cybergoths”. Are they rehearsing for some play? Or are there really people who dress & act like that for recreation?

April 17, 2021 at 6:09 pm

If sharing a meme of a black person is racist, then watching sports with black athletes or movies with black actors is also racist. I’ll just avoid such tings. Thanks for the lesson.

April 18, 2021 at 5:24 pm

Hi Diego,

Whittaker is making a pretty careful argument explaining why sharing those memes is problematic (and when it is, which is not necessarily always!). And there’s no reason to think that, if he’s right, then the things you say follow from it. Please only engage if you’re genuinely interested to discuss the issues at hand. Comments like this aren’t productive for anyone.

April 17, 2021 at 8:58 pm

There you go with that raciss math again!

April 18, 2021 at 5:28 pm

Hi “Buck”, I know your delicate sensibilities probably brace at this, but you can say fuck here, it’s okay.

May 16, 2021 at 3:30 am

This is a wonderful piece of writing!

May 19, 2021 at 2:02 am

Ah yes, symbolic “fight” for things that are unimportant instead of focusing on actual problems that afect the poc communities

June 7, 2021 at 3:26 pm

Nicholas, you write ‘The image of the boy as circulated is a cropped image; the original photo reveals him standing behind a young girl that, Taylor suggests, he has a crush on. ‘ When you say she ‘suggests’ this – does this mean it is her guess? Is she just her projection onto the image? Or does she have some evidence that he has a crush on her and is expressing that?

Furrhermore, does it matter what the reality is? The point with symbols is they take on a life of their own. They are used for communication and aquire a certain meaning in common discourse…

Though I can see that there is something problematic about taking (any) human beings to be symbols for something, rather than the complex, vulnerable, living beings they are.

I mean, take the famous (white) girl looking evil

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/29/arts/disaster-girl-meme-nft.html

You could say it must be quite tough being a widely used symbol for evil intent. Though the celebrity can be beneficial for the individual too. (And, in this case, so is the cash).

Finally, how does this example bear upon the discussion of race. I guess if this girl had been black then you would be claiming it is racist to use her as a symbol of evil; but then why not claim it is racist given that she is white? Which would be to say that this image should not be used whatever her colour….

I

October 11, 2021 at 3:09 pm

Because she is white.

February 24, 2022 at 5:05 pm

A piece of evidence that this article is well-written is that I had an idea for one way to answer the closing question (“what would … a generative, radical, socially connective, powerfully black memeing practice look like?”) long before the end of the essay. It naturally invites the imagination to explore the implications of these ideas, long before that concluding piece of thought-provocation is asked.

I’ve been uncomfortable with using memetic images of people, especially given how race plays into the use of memes, and from this essay I was able to garner a deeper understanding of why: The lack of context and connection to those real people. Adding some text to the meme explaining why I chose it can both clarify intent and humanize the image – e.g., “Right now I feel like Serena Williams serving – I’m starting a big project at work, and feel like I’m about to do something great”. This forces me to (a) choose images whose context I understand fairly well, and (b) provide information about the images that others can use to learn more, which can boost visibility of the human behind the image and not just of the image itself.

Thank you for taking the time to write this piece, and for offering up your deep thoughts on this matter for all to read.

March 25, 2023 at 8:08 pm

Reading the article, I found it made a very convincing case that the conventional understanding of digital blackface isn’t problematic. It’s weird to see both sides of the issue both having read it differently… Almost like no one, whether you think digital blackface is or isn’t problematic, even read it…

March 26, 2023 at 9:30 am

lol i dont even use those lame ass memes anyway, nothing of value lost here.

December 29, 2023 at 10:08 am

I only came here just to download a picture LMAO