What follows is a guest post by Helen De Cruz (Saint Louis University). She is the editor and illustrator of the recent book Philosophy Illustrated, forty-two thought experiments to broaden your mind.

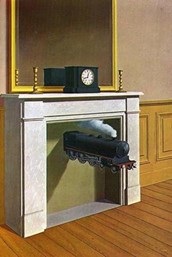

Pictures may seem like a strange way to philosophize, since people tend to think of philosophy as existing exclusively in written tomes. However, once you let go of the notion of philosophy as abstract ideas put into writing, you start to see it in lots of places. Think of René Magritte’s surrealist paintings such as his “La Durée Poignardé” (literally: Duration Stabbed, but translated more figuratively as Time Transfixed), which features a train racing out of a fireplace. To reflect on this picture requires active engagement and imagination on the part of the viewer.

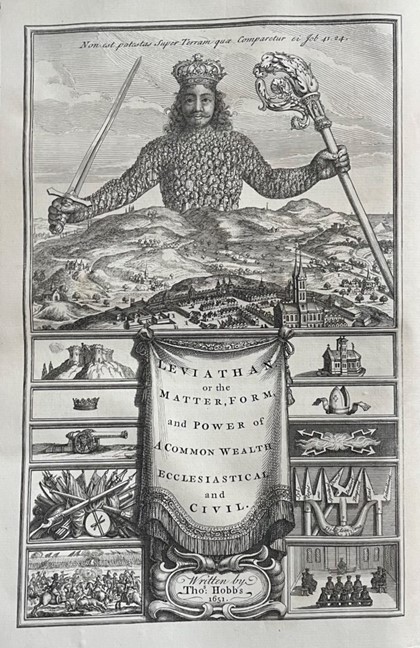

Further in the past, philosophy in the visual mode was even more common. Medieval Europeans shared a rich visual vocabulary that populated their paintings, illuminations, and sculptures. In the early modern period, philosophical pictures were an established art form (Susan Berger’s wonderful recent book offers many examples). The frontispiece for Thomas Hobbes’ 1651 magnum opus, Leviathan, was designed by Abraham Bosse in close consultation with the author. It exemplifies Hobbes’ idea that a “A multitude of men” could be made of “one person,” who “must be considered as the voice of them all.” The image of the looming monarch illustrates this perfectly. He literally gives shape to a mass of people who would otherwise be constantly at war with each other, gazing out confidently at the viewer with his crozier and sword.

Visual philosophy is cross-culturally ubiquitous. In East and Southeast Asia, scholar’s rocks are intricately shaped natural rocks reminiscent of mountains that convey abstract ideas of emptiness and fullness, inviting scholars to cultivate their minds through the contemplation of the stones. The Japanese rock and sand garden elicits mindful viewing and moral cultivation. The viewer is engaged in philosophy by active reflection on these objects. As such, philosophy in the visual mode is open-ended and interactive, putting the viewer in the role of an active participant and a fellow philosopher.

I started drawing philosophical thought experiments a few years ago, with the explicit aim of providing visual philosophical commentaries. My pictures are not standalone, but meant to be viewed in conjunction with the thought experiment. I wanted to do more than just make pretty pictures or explicatory diagrams.

Take, for instance, Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. It was one of the last pictures I added to the collection of forty-two thought experiments (which took about three years to complete in all). It was hard to conceptualize, perhaps because there are already so many visual representations of the story. It presents an unforgettable image of people shackled against a cave wall, watching reflections of various objects dart in front of their eyes which they take to be the real things. Plato invites us to ask what would happen to the prisoner who was released from their fetters. How does their perspective change? I did not want to make a diagram of the cave, but rather evoke its emotional resonance. Eventually I conceived the allegory as a hero story one might find in young adult fiction. The main character escapes the cave through education, at first seeing lights indirectly and reflected in the water before she can just barely take in the dazzle of the sun. I made her into a woman, to reflect Plato’s belief that women can be philosopher-queens, and the style is both reminiscent of the American comic and Greek Attic vases. I ask the viewer: what does it mean for you to be so personally transformed through education?

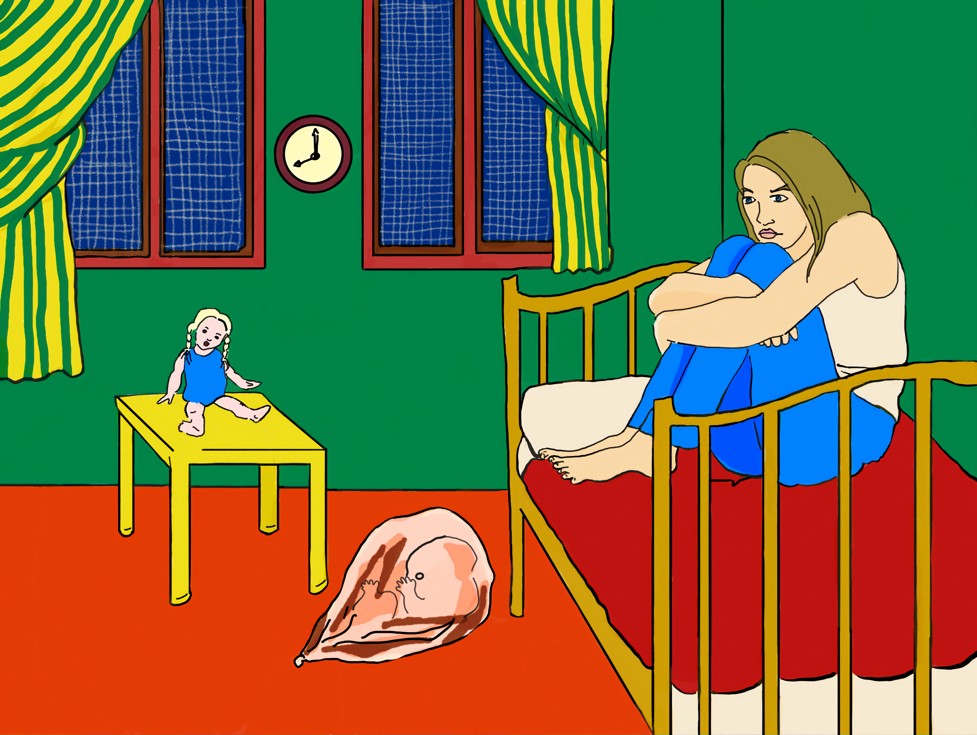

Prior historical periods enjoyed an extensive shared visual vocabulary, unlike the wide range and diversity we see today. Still, in drawing many of the thought experiments, I took advantage of the abundant references we do share. This can bring out deeper layers of meaning. Consider “People Seeds.” This thought experiment occurs in Judith Jarvis Thomson’s 1971 paper “A Defense of Abortion.” It is a disturbing little tale, a horror miniature:

People-seeds drift about in the air like pollen, and if you open your windows, one may drift in and take root in your carpets or upholstery. You don’t want children, so you fix up your windows with fine mesh screens, the very best you can buy. As can happen, however, and on very, very rare occasions does happen, one of the screens is defective; and a seed drifts in and takes root.

The story obviously does not capture all the intricacies of pregnancy, nor is it meant to, but it focuses on the horror of contraceptive failure and the lack of control one feels when this happens. Taking the horror genre as inspiration, I chose a protracted, uneasy perspective, unnatural colors, and of course a creepy doll, using the color schema and perspective of the children’s bedtime classic Goodnight Moon by Margaret Wise Brown.

Others may recognize the allusion to Vincent van Gogh’s Bedroom in Arles. The room, which depicts the artist’s own bedroom and reflects his uneasy state of mind is very narrow, and the perspective of the bed was suitable, so as to create a feeling of oppressiveness as the people seed takes root. Finally, I wanted to incorporate religious imagery, particularly given how the abortion debate in the US and other countries has been shaped by religious considerations. The obvious visual reference for this is the Annunciation, where the Virgin Mary learns from the angel Gabriel, to her shock and dismay, that she is pregnant. The parallels to unplanned pregnancy are strikingly similar. I took inspiration from paintings where Mary appears vulnerable and confused, such as Ecce Ancilla Domini! by Dante Gabriel Rosetti. Ultimately, not all readers will spot these references, but I think taking advantage of this rich, tacit visual vocabulary helps us to look at thought experiments with fresh eyes.

To take Philosophy Illustrated from a hobby project into book form, several creative ideas had to come together. I wanted the book to feel like a box of intellectual chocolates to be indulged in piecemeal or binged, using the picture and the accompanying text as a starting point for the reader’s own engagement. Each of the forty-two thought experiments features one illustration, a retelling of the thought experiment, and a brief reflection by an expert in the field on what it might mean, followed by a few questions for the reader and additional sources. I am very grateful to my editors at Oxford University Press for giving me the freedom to carry out that vision.

To accompany the illustrations, I wanted to have contributions by philosophers on each thought experiment. Each thought experiment has a brief reflection by an expert (including Aesthetics for Birds’ Alex King!), who in some cases is the original author of the thought experiment (as for Ruth Millikan’s “Accidental You” or Tamar Gendler’s “Skywalk”). In this way the book has become a massive collaborative and polyphonic project.

Second, I included thought experiments from a wide range of philosophical traditions. For example, the below image illustrates Mengzi’s Child at the Well, which has been widely debated in Chinese philosophy. It was conceived in the Warring States period (475–221 BCE) and invites us to think of the spontaneous reaction of alarm and compassion we would feel if we saw a child teetering at the edge of a well. The image focuses our attention on the central role of empathy and our spontaneous other-regard, and brings the immediacy of the moment out. According to Mengzi, there is no time for selfish deliberation and so our concern in such a situation must be purely other-regarding. Many later Chinese thinkers, such as Zhu Xi and Wang Yangming reflected on this story, and with the picture and Bryan Van Norden’s reflection, we invite the reader to do the same. The book also covers thought experiments by Avicenna, Nagasena, Asanga, Zhuangzi, Ibn Tufayl, and more.

I also wanted to the illustrations themselves to include a diverse cast of people to reflect that anyone can be a part of philosophy, a discipline that has been marred by elitism and exclusion. We know from the psychology of narratives that people tend to imagine situations using “default” representations. Unconscious imaginings often play into our stereotypes and implicit biases. In the case of philosophical thought experiments, these are heavily influenced by the prevalence of existing representations of philosophers as white and male. If a thought experiment involves two people named “Smith” and “Jones” and just a few lines, then it is easy to default to a visualization of two (rather schematic) white men in ties and suits in an indistinct setting.

I drew the pictures in Philosophy Illustrated with the aim of showing diverse people (in terms of gender, race, age, body shape, and other characteristics) in various philosophical situations. The people behind Rawls’ Veil of Ignorance are, like actual political deliberators, diverse in terms of gender, race, and ability. They reflect on how they would fare in a world where they might be in a different situation, exemplified by the figures behind the veil. John Wisdom’s Invisible Gardener shows two genderqueer people.

Philosophy Illustrated fits within my broader aims for making philosophy more collaborative, inclusive, and accessible. To this end, I have selected thought experiments from a wide range of philosophical traditions, visually depicted a wide range of people, and incorporated a wide range of media. I have a few other projects in the works, including an illustrated edition of Margaret Cavendish’s Blazing-world (1666) in collaboration with philosopher Gwendolyn Marshall. My upcoming trade book Wonderstruck (under contract with Princeton University Press), which will discuss the centrality of awe and wonder shaping our thinking and cultural engagements. It will feature black-and-white images for each chapter. My hope is that a book of illustrated thought experiments will make philosophy more accessible to a broader range of people, help us to engage with philosophy in different ways, and make a small contribution to revolutionizing the field.

Helen De Cruz holds the Danforth Chair in the Humanities at Saint Louis University. She is the author of A Natural History of Natural Theology (MIT Press, 2015, co-authored with Johan De Smedt), Religious Disagreement (Cambridge University Press, 2019), and Wonderstruck: How Awe and Wonder Shape the Way We Think (forthcoming with Princeton University Press). She tweets at @helenreflects. Website: https://helendecruz.net/

August 23, 2022 at 7:45 am

This kind of thing needs more encouragement! I’ve done varieties of this in my classes. In my Magic(al) Realism course, the students’ final project is creative, and I’ve had students visualize short stories. In my college writing class, they’ve done “infographics” that contain some text, but visuals dominate. Even the reader we use has a “Visualizing X” at the start of each topic (education, the sciences, wealth & poverty, etc.). As you point out, this a long tradition in many cultures—and I love your take on it. That “abortion” illustration is sad and chilling at once. Thanks for sharing this.