Tiki bars exist today as a result of American violence and colonialism in the South Pacific. Despite this, they are idyllic and peaceful spaces where you can sip on a tropical cocktail to escape from your everyday worries. The idealization and exotification of real places seem essential to the escapism of tiki bars, so how can we justify the revival they are experiencing today?

Tiki bars are an American creation that takes rum from the Caribbeans, imagery from the Pacific Islands, and food claiming to be from Asia to create the illusion of a tropical paradise on the continent. They are decorated with artificial waterfalls, bamboo and rattan furniture, statues vaguely depicting Polynesian deities, and lush artificial tropical plants. The word tiki itself originated in New Zealand to refer to a carving of a first man or a god. However, the word has been appropriated to describe “any Polynesian carving with a largely human form, exaggerated features, and a menacing visage,” most of which are created in the United States.

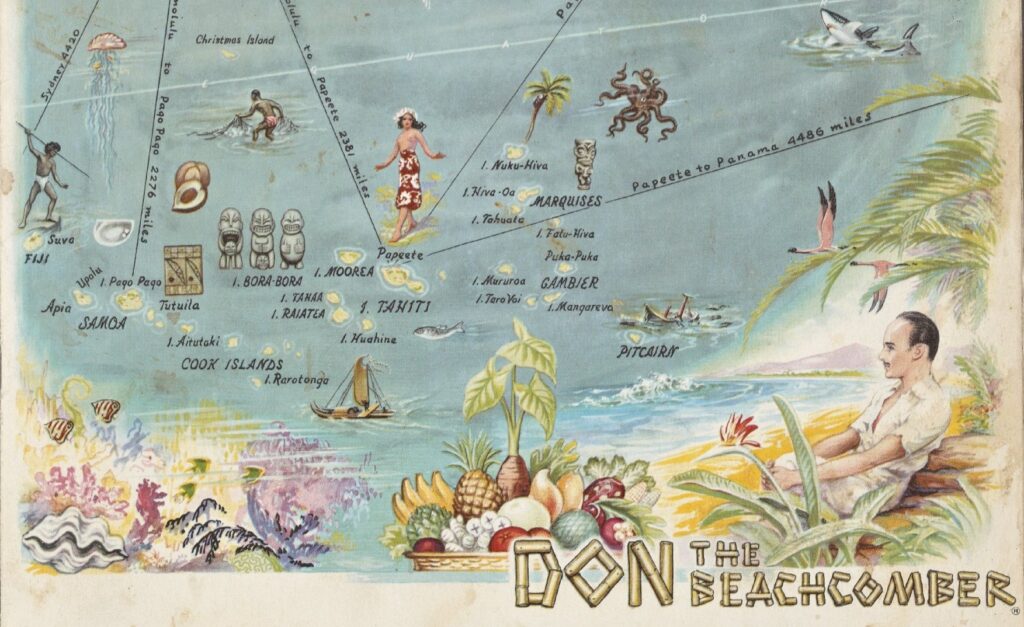

Ernest Raymond Beaumont Gantt opened the first tiki bar, Don the Beachcomber, in California in 1933. Gantt had traveled to the Caribbean and the South Pacific when he decided to “bring paradise” back to mainland America. Traveling to those islands was not common then, so Grantt was able to craft a fictional culture that mashed together various traditions and sold it as a unified vision to customers who never left the continent. He started mixing what he called Rhum Rhapsodies, which became extremely popular as Prohibition was just ending. By 1937, he had legally changed his name to Donn Beach, fully embracing the persona of the beachcomber.

The tiki craze continued to grow in the coming decades. As World War II ended, soldiers returned from the South Pacific with stories about the people they encountered while militarizing the Oceanic islands. One of those veterans, James Michener, wrote Tales of the South Pacific, a collection of short stories based on his experience in Vanuatu. The book fueled the American obsession with the tropical islands, and its success led to adaptations into a musical and a movie. Around the same time, in 1959, Hawaii became a state. The subsequent lifting of travel restrictions and the relative ease of flying there made the tropical lifestyle an attainable possibility for many Americans. From there, in addition to the quintessential tiki bar, tiki-themed motels, bowling alleys, and apartment buildings were sprouting all over the United States.

Americans created tiki culture for Americans, doing with Polynesian culture what they did to the word tiki itself: removing it from its context and using it as a prop to create an undefined exotic paradise. Yet, those problematic roots seem distant to us today as tiki experiences a revival. First, it was always just a show—the tiki bar was never meant to accurately portray the atmosphere and flavor of actual tropical islands but create a distinct fictional world where Americans could play at being on vacation. Second, tiki has also become a subculture of its own. Today, tiki revivalists try to recreate the distinctive, retro-American culture of tiki bars from the 1940s and 1950s. They are not appropriating Polynesian artifacts and practices that inspired the original movement but rather the fictionalized culture that resulted from the amalgamation of Polynesian, Caribbean, and Asian cultures.

Those two excuses do not absolve the revivalists. They are still participating in (and actively trying to revive) a movement that turned religious Polynesian imagery into mass-produced receptacles for rum concoctions. Even so, tiki revivalism need not be seen as problematic. Appropriation is not essential to it, so you can escape in the comfort of your next Mai Tai without any guilt. But understanding why takes us through a little more history.

The Comforts of Escapism: Tiki and Kitsch

Tiki bars were first popularized in Los Angeles, far from the tropical islands they claim to mimic. Transporting the customers from the busy streets of Los Angeles to a quiet Polynesian beach requires nothing short of a spectacle. Martin Cate, owner of the San Francisco tiki bar Smuggler’s Cove, writes that contrast enhances the sense of escape: dramatic shifts from innocuous exteriors to extravagant interiors or from urban settings to tropical gardens.

It is no coincidence, then, that tiki bars thrived next to Hollywood. Before opening his bar, Donn Beach worked as a technical advisor for films set in the South Pacific, where memorabilia from his travels became movie props. This air of inauthenticity is why tiki bars are sometimes considered kitsch. Kitsch is hard to define, but it is often associated with decorative objects that evoke cheap and false emotions, especially when those objects are superficial imitations of something real. For example, “Live Laugh Love” signs used as home décor are kitsch because there is something naive and sweet about being uplifted by those three words.

Literary critic Matei Călinescu characterizes kitsch as “a specifically aesthetic form of lying.” This fits tiki to a tee. The tiki bar lies about where you are and what time it is: the windows are shut because “the last thing you want on your voyage … is to look out the windows at roaring traffic,” and lighting is kept dim to keep the space “enveloped in perpetual twilight.” The tiki bar also lies about what part of the world it is trying to transport you to by mashing together knickknacks from around the globe to create exotic scenes. Tiki uses its décor and imageries not to represent a part of the world but to create an illusion. Cate actively resists calling tiki bars kitsch, and he may be right to do so—it is “serious fantasy!” Still, there are undeniable parallels between the two.

In the same way that anything can be kitsch, anything can be tiki.

Kitsch, according to philosopher Thomas Kulka, depicts subject matters that are emotionally charged in a readily recognizable way to easily trigger emotions from its audience. It relies on associations that we are expected to make: the cuteness of kittens and the sweetness of babies, for example, are common themes. Kitsch tries to provide unmediated access to its subject matter, not because it wants to familiarize its audience with the depicted object, but instead because it wants to provoke an emotional response easily.

Kitsch must satisfy our existing expectations to stir up consistent and uniform emotional responses, as philosopher Kathleen Higgins has argued. It triggers a sense of belonging to a larger world because we feel like it evokes emotions others will share. “In enjoying sweet kitsch,” she writes, “one enjoys, not the object, but one’s own state of mind.” For Higgins, kitsch is appealing because of what we bring to our experience: pleasant beliefs and desires that we carry within ourselves and a sense that the world is as wonderful as it is presented to be. The depiction of the subject matter is only a means of invoking the audience’s cultural associations to evoke a specific state of mind. That state of mind—the feeling of reassurance—is what makes kitsch appealing.

Much like kitsch, the appeal of the tiki bar does not lie in its objects (its drinks or décor) but in what it triggers in us. The tiki bar is created for Americans on the continent as a space for escapism; it deploys tropes and imagery that remind its customers of an exotic paradise without accurately depicting any real tropical island. Tiki, like kitsch, is not concerned with what it depicts or whether it depicts its subject accurately but with how we respond to it. The customer, sipping on their extravagantly garnished cocktail, reflects on how wonderful it is to live in a world where you can escape to a beautiful island and leave your worries behind. Indulging in this illusion and believing that it is attainable is what makes the tiki bar so appealing. The palm fronds, the bamboo decorations, and the rum concoctions are only there to facilitate this fantasy. We like tiki bars because we like the idea of tropical vacations, and the objects and drinks in the tiki bar invoke the customers’ associations to satisfy their escapism.

Some objects are very good at triggering those associations. Tiki bars often feature natural materials from the South Pacific: bamboo poles, sisal rope, and sea grass rugs. Nautical décor like anchors, ship’s wheels, and harpoons can adorn the walls. They also often include artificial waterfalls, fountains, or aquariums. Water features bring the customer closer to the beach and immerse the space with relaxing natural sound. Everything in the tiki bar should provoke your sense of adventure. Take the Mai Tai, the quintessential tiki drink created by Trader Vic, Donn Beach’s contemporary. A Mai Tai is traditionally decorated with a mint sprig and a lime shell (the hollowed-out half of the lime that is juiced to make the drink). The garnish should, very literally, look like a little tropical island (the shell) with a palm tree (the sprig) lost in the waves of your rum concoction.

Other objects only satisfy our escapism because of the cultural associations that we bring to the table, and those have evolved since the birth of tiki and will continue to evolve as our sensitivities change.

Tiki’s Exploitative Roots and How to Move Forward

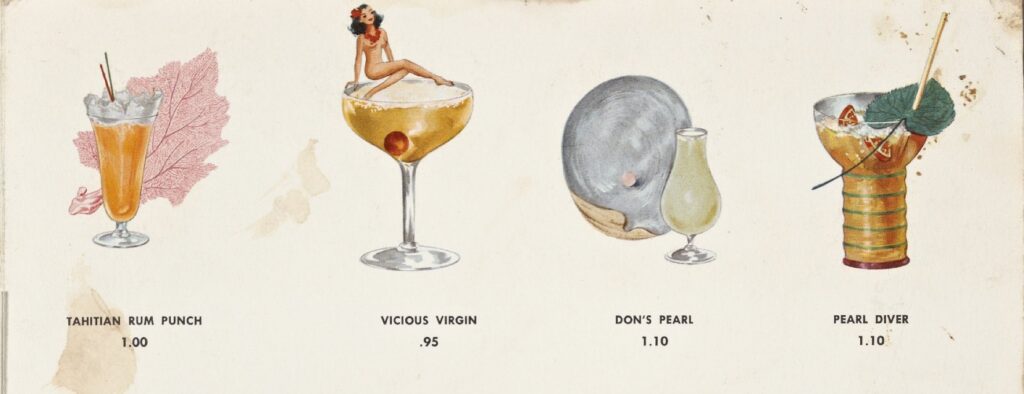

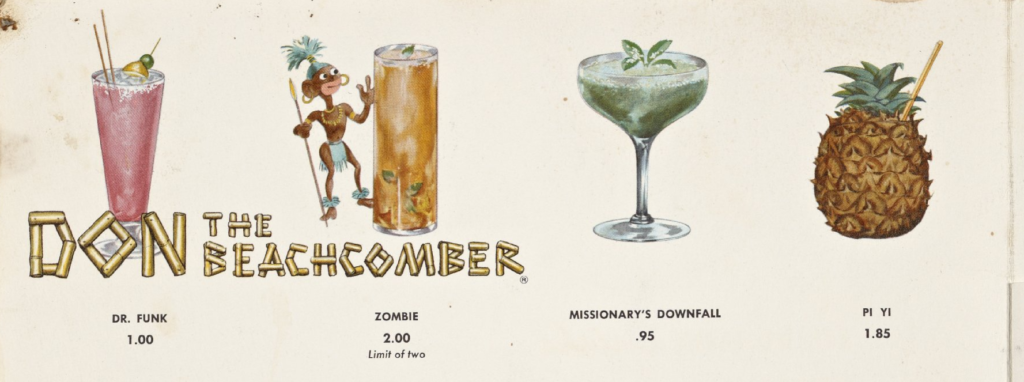

In the ’40s and ’50s, tiki bars mimicked the exotic, tropical, and dangerous based on what Americans considered foreign and fascinating at the time. We might worry that this fascination originates in dangerous entitlement that sees foreign cultures as there for the American tourist to explore and exploit. After all, Trader Vic gets his nickname from trading travel memorabilia for food and drinks. And the cover of Don the Beachcomber’s menu (above) depicts Donn Beach as a domineering figure over the islands of the Pacific.

It’s hard not to notice that the drinks menu for Don the Beachcomber also, rather unnecessarily, deploys disturbing racist and sexist depictions of native Polynesian people. But tiki’s exoticism was not limited to the South Pacific. African masks and Melanesian figures became part of tiki décor since they were unfamiliar enough to the American at the time to evoke the right emotions. They create “an atmosphere of relaxation, wonder, mystery, or even danger,” which Cate writes is key to a successful tiki bar. The fascination with exoticism and escapism in the mid-twentieth century was naive but earnest, and it was because of this uncritical attitude that tiki was able to emerge. Just like kitsch, tiki removed the complexities of its subject matter. What was offered to the customer, instead, was an idealization.

Increasing global awareness in the ’70s and ’80s led to the decline of tiki, which was seen as inauthentic and racist. Tiki flourished in the postwar context of an “uptight, conservative, conformist Eisenhower-era America” where “fear of nuclear winter, fear of blacklisting during the Red Scare, fear of missing a payment on your 30-year-old mortgage, fear of not fitting ruled the day.” It is therefore no surprise that, as tiki revivalist Jeff Beachbum Berry notes, the fantasy of escaping to a tropical paradise was a powerful one. The need for such fantasy is one explanation for why tiki is experiencing a revival today. While its comeback is often attributed to the recent craft cocktail revolution, it also seems like we especially need an escape these days.

What we associate with a tropical vacation and what triggers our sense of escape has changed over the last century. Tiki, I believe, has little to do with Polynesian culture, Hawaiian paradise, and Oceanic idols—those are just the imageries that happened to evoke escape and wonder in the ’40s and ’50s. While these imageries are important to the history of tiki culture, tiki must now find and employ the cultural associations of the current age.

This sort of updating happens all the time. We can see it in the evolution of ingredients that make up tiki drinks. Take fruits and juices. Donn started by using pineapple and passion fruit. Later, guava and lychee became more common. Today, yuzu and dragon fruit make frequent appearances on the menu. In the same way, the imageries that we can use evolve as well: we can remove appropriative religious symbols and racist and sexist depictions of native people without losing what makes tiki tiki.

Just as there is no object that is inherently kitsch, there is no object that is inherently tiki: its status and our enjoyment depend on our own states of mind. Nautical and tropical themes that do not misrepresent important cultural symbols can evoke our sense of escapism, maybe better than the outdated imagery of the tiki bars of the previous century. Or we could organize tiki bars around yet other principles. Robert Adamson, co-owner of the California tiki bar Strong Water Anaheim, explains that the décor of his bar consists simply of “things that my wife didn’t want in the house.” In drawing the parallels between kitsch and tiki, we can see that there are ways forward for the movement.

Even so, some level of idealization seems necessary for both kitsch and tiki. Kitsch triggers a uniform emotional response in its audience. This sentimentality requires that the subject matter is oversimplified and sometimes misrepresented. As Higgins puts it, kitsch must exclude what is intolerable from its subject matter, and our enjoyment of it must be unreflective. Similarly, tiki requires that we put our worries aside and allow ourselves to be transported to tropical paradise. To reflect on the history of tiki imageries and the exploitative nature of the culture would go against everything that tiki is about.

But the business of creating paradise requires that we look for it. While Donn Beach explored the South Seas to create his own piece of heaven, tiki revivalists seem less interested in Polynesia and more interested in the fictionalized American version of it. They are hunting for tiki artifacts from the past century in Los Angeles instead of riding the high seas in search of treasure. And maybe that’s the right place to be looking: paradise is not found but created with carefully selected movie props. Sven Kirsten, maybe the most influential tiki revivalist, puts it this way: “Nowadays—through the Internet, television, and documentaries—we’ve become very aware that paradise on earth does not exist. Even these South Seas islands have their own complex problems and set of rules and were not as idyllic as the Western World wanted them to be. But the human being created this illusion because it has an innate need to believe in paradise on Earth.” Tiki is about indulging in the belief that paradise can exist with a Mai Tai in a windowless bar between a parking lot and a bus station.

Karim Nader is a postdoctoral associate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His research is on technology, aesthetics, and ethics generally, and on virtual reality, video games, and fiction specifically.

July 21, 2024 at 8:29 pm

And thus essay has no mention of Tiki Ti, the 4 boys or the Philippino diaspora who was vital in getting Tiki off the ground.