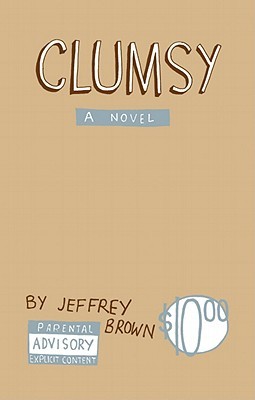

Jeffrey Brown (photo by Jill Liebhaber)

Comic Artist Jeffrey Brown interviewed by Christy Mag Uidhir

Jeffrey Brown was born in 1975 in Grand Rapids, Michigan. While earning his studio MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Brown abandoned painting and began drawing comics with his first autobiographical book Clumsy in 2001. Since then, he’s drawn nearly two dozen books for publishers including TopShelf, Chronicle Books, Simon & Schuster, and Scholastic. Brown has also directed an animated video for the band Death Cab For Cutie, had his work featured on NPR’s ‘This American Life,’ and co-wrote the screenplay of the film Save The Date. His book Darth Vader and Son was a NYTimes #1 bestseller, and its sequels Vader’s Little Princess, Goodnight Darth Vader, and Darth Vader and Friends, along with his middle grade series Jedi Academy, were also NYTimes bestsellers. His art has been shown at galleries in New York, Los Angeles, Paris, and the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. Now teaching comics at SAIC, he lives in Chicago with his wife Jennifer and two sons.

A rather significant portion of what many would consider to be the best comics of the last 25 years have been (broadly construed) autobiographical.

- Chester Brown, Paying For It

- Harvey Pekar, Joyce Brabner, & Frank Stack, Our Cancer Year

- Eddie Campbell, Grafitti Kitchen

- Marjane Satrapi, Persepolis

- David B., Epileptic

- Art Spiegelman, Maus

- Alison Bechdel, Fun Home

- Craig Thompson, Blankets

- Jeffrey Brown, Clumsy

Do you find there to be something unique about the medium of comics that lends itself to autobiographical narrative—especially when compared to its purely textual or purely pictorial kin?

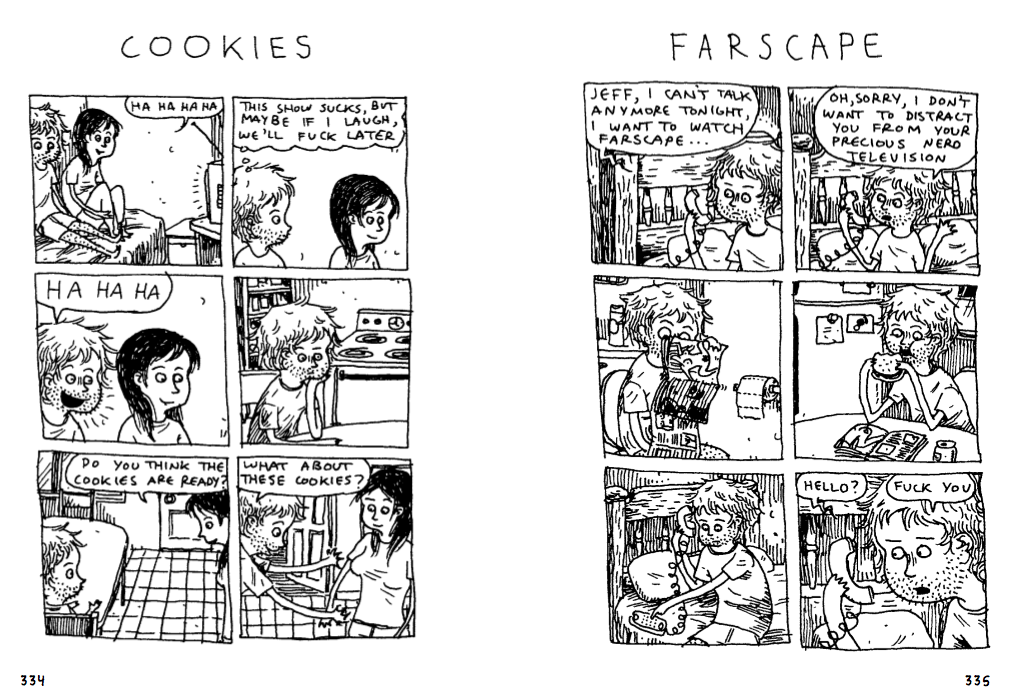

I think with comics, the author’s voice can become pervasive throughout the form in a way that can’t be repeated in almost any other form. The style of drawing in comics can be as much an element of voice as handwriting, and the nature of self-depiction – coupled with the ability of comics to use exaggeration within a realistic depiction – can give comics a sense of emotional immediacy that creates a sense of physical manifestation of the author’s interior life. For readers, the effect of reading an autobiographical comic can be one of intense closeness to the author, breaking down the separation that naturally comes with interpreting a work of art. This is also helped by the tendency of these autobiographical comics to be the work of a single creator who is not only writing the story, but drawing, lettering, coloring, and even completing the production and design of the book. Contrast that, for example, with film where there are so many people involved you’ll rarely, if ever, see something as a finished piece that could be classified as autobiographical.

Of course, few of these autobiographical works would strike anyone as being especially challenging or innovative with respect to either narrative and depictive/stylistic convention or to the comic medium itself. Do you find there to be something about the nature of autobiography that might discourage comic artists from undertaking substantial departures from standard narrative and depictive conventions?

Personally, I try to not worry about whether I’m following conventions or being formally innovative, in comics specifically or even within art in general. I think that experimentation for the sake of experimentation can lead to interesting work, but the best work is that which focuses on the ideas it attempts to express, and letting the form be defined by that, rather than vice versa. I also think there isn’t enough perspective on comics or autobiographical comics to determine exactly where things will fall – simply not enough time has passed to know what will be considered innovative or conventional, and the history of what follows these works will shed more light on them. That is, any of these works alone may be completely conventional, but within a continuity of works, some may be important parts of chronologically later work that is deemed innovative by whatever standards are used. That said, I don’t know how much innovation or stylistically challenging any work in any medium is currently, certainly nothing that isn’t overlooked or marginalized, except maybe the comics of Chris Ware. I also would argue that Maus is innovative, and Justin Green’s Binky Brown is another autobiographical book that at the time was challenging within the comics medium and in terms of autobiographical work. As an artist, my interest has always been first aligned with content, and I would rather rely on current conventions to get the most effective expression of my ideas than concentrate on coming up with new formal innovations.

What do you consider to be the limits, aims, and obligations of autobiography to be for your own work and how might these be (best) served by the scratchy, minimal style and heavily fragmented narrative most evident within your earlier works?

The limit, as with any autobiography, is viewpoint. Unless you want to make it into something that’s not autobiography, it’ll always be the author’s own viewpoint, even if they try to tell the story from someone else’s viewpoint. With my autobiographical comics, I’ve tried to present things almost as documentary, by removing things like narration and interior thoughts, but it’s still very much my story, or at least, part of my story as told by me. I don’t think there are any obligations, necessarily, but I try to be sincere in my work. I try to present life as flawed and everyday moments as important, and the scratchy, seemingly unedited style of those early autobiographical books is something that signals the reader that the story is something personal and vulnerable, which is an emotional entry point for them to let their own guard down. As for fragmentation, one thing I was interested in was memory, specifically how our memories reconstruct events to give meaning. The story of boy meets girls in reality may be chronologically boy meets girl, boy dates girl, boy and girl fight, girl leaves boy. That isn’t how someone remembers a relationship, though, instead it comes in bits and pieces, remixed by the brain so that one event connects across time and space to another event that, on the surface, is completely unrelated, but within the context of what those events mean to the person, and how those experiences achieve and maintain significance, these events need to be reordered to properly reflect the truth of the boy meets girl story for that person. I also like the idea of a narrative being constructed as much by the reader putting these parts together as they read, so that missing details are sometimes inferred, or even informed by the reader’s own history and personality.

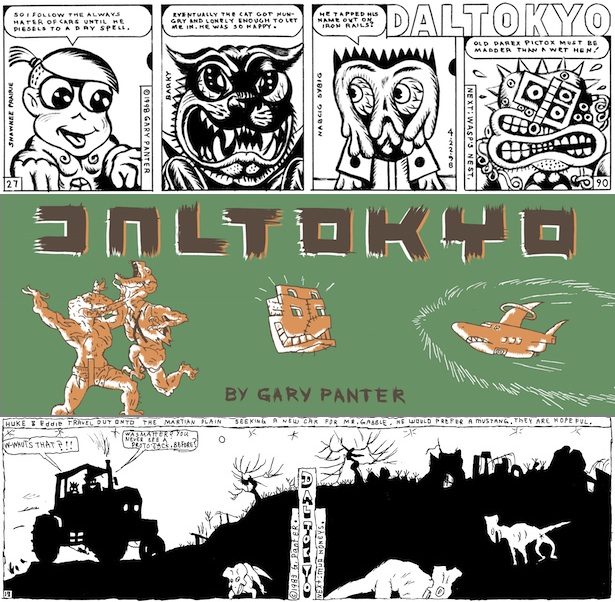

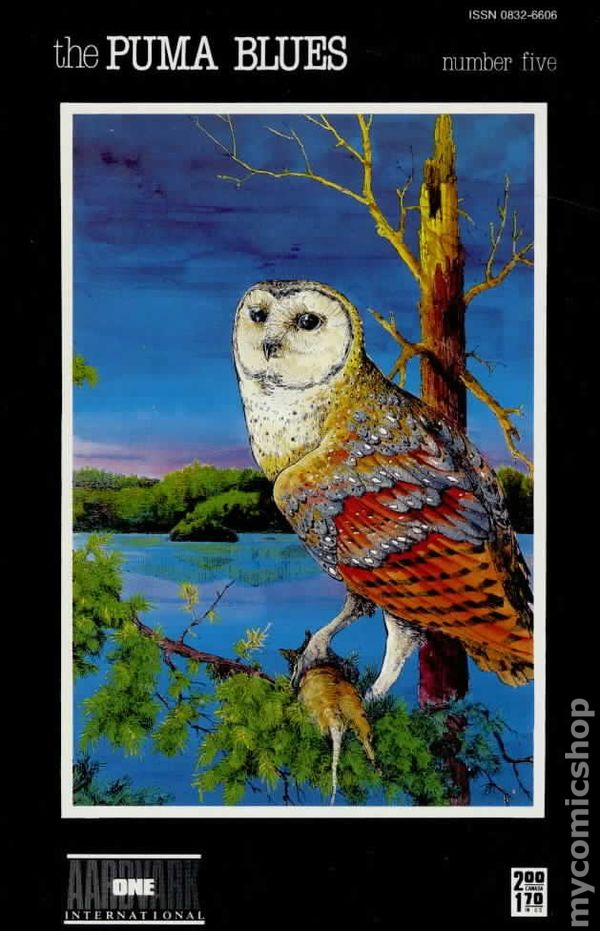

While the literary world has certainly taken notice of comics (e.g., Watchmen routinely ranks amongst the top 100 novels), the world of fine art has shown comparatively little interest in comics—and perhaps unsurprisingly there are comparatively few comics with characteristically fine-art miens (e.g., Gary Panter’s Dal Tokyo, Stephen Murphy & Michael Zulli’s The Puma Blues). How has the artworld reception of comics changed since you began your career a decade ago?

There’s definitely was more interest, though it’s perhaps a backwards entry – it’s the art world coming around to realize that people are interested in comics, and so attempting to capitalize on that, rather than the art world having made some judgment about the aesthetic value of comics that the general population will then catch up to. So the art world is a little behind, much in the way that rock and roll or hip-hop were not taken seriously at first as musical genres. When I was attending The School of the Art institute of Chicago, there were only a handful of other people making comics in the whole school, and now I’m one of a dozen faculty teaching comics classes, and the classes are consistently full. I think where comics fit in the art world is something else that will be detrmined over time, so it’s hard to say where it is now, where it’s going, where it should be. Which is why I always return to the basic premise of what am I trying to express, and am I doing that effectively. Whether Clumsy is in a comic shop, a bookstore, or in a gallery is secondary to the question of whether someone looking at and reading it is engaged in a meaningful aesthetic experience. If they’re not getting any benefit on some intellectual or emotional level, then it doesn’t really matter what definitions are assigned to the work, or where the work is categorized.

On the view that contemporary fine art aims to maximize (rewarding) public meaning, understandably one might find the traditionally and comparatively strict and overt intentional aspects (both narrative and figurative) of comics to be excessively limiting. When it comes to work meaning, do you take your relationship with the audience to be more conversational (i.e., the artist intends her work to communicate such-and-such meaning to the audience, which if properly informed, should be able to read that intended meaning off of that work) or merely facilitative (i.e., the artist intends to provide the audience a broadly interpretable work facilitative of multiple rewarding meanings, intended or otherwise)?

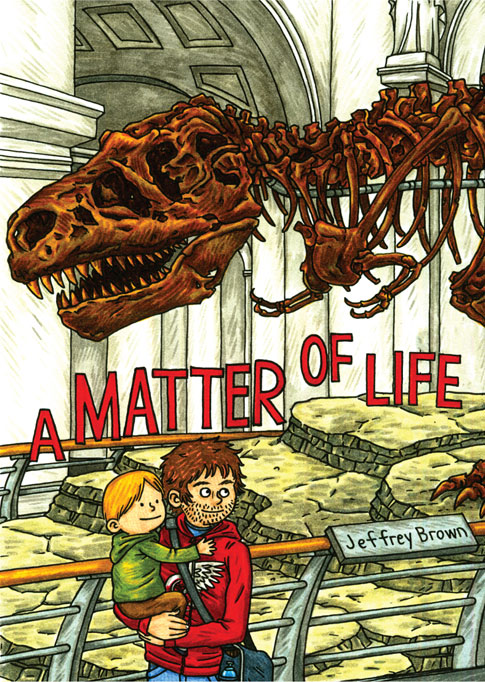

I try to make work that is more broadly interpretable, and judging from the response to my autobiographical work, I think I’ve been somewhat successful. The range of responses seems to vary according to individual tastes, personalities, and experiences. With my book Clumsy, I’ve heard people say I make myself out to be the hero and I’ve heard others say Theresa is the hero. What’s important to me about the book isn’t my story – it’s not about what happened to me, it’s about relationships and how they are in real life, not fairy tales and not tragedies but something both completely mundane and yet world ending, something beautiful and worthwhile even when they tear you apart. It’s also not just that I want people to get that, though, but I want them to think about their own relationships and lives, to reflect, to find their own meanings and clarify their own understanding of the world. It was meant as a criticism, I think, but one reviewer talked about how my most recent autobiographical book A Matter Of Life raised more questions than it provided answers, but that’s exactly what I wanted it to do. For me, creating art is also an attempt to understand the world better, and part of that understanding comes from the response of the audience to it, and their interpretations.

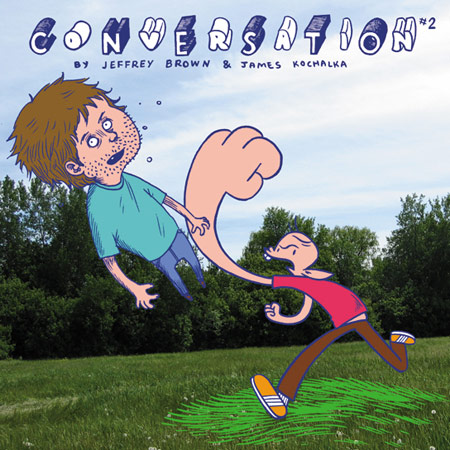

Do you find that you differ in this regard from that of your fellow comic artists (e.g., the perhaps aptly titled Conversation #2 shows you and James Kochalka to occupy very different art-theoretical space).

I’m not sure, as I think most cartoonists tend to either not think about these things, or at least, not talk about them. I think there’s a wide range of views, and it’s probably wildly inconsistent, though I think there’s more and more artists who are well informed about what art-theoretical spaces they want their work to live in. I think there are a good number of artists whose ideas would line up fairly close to mine.

Given your extensive background in painting, and recent foray into film, having co-written the screenplay for the film Save the Date (2012), do you see the comic medium as aligning more with the Literary Arts rather than the Visual Arts or existing somewhere in between (and in that sense perhaps not wholly unlike screenwriting)?

When I think about comics, good writing can often overcome bad artwork, but great artwork rarely compensates well for bad writing. On the other hand, the art and writing are so interdependent I don’t know that it’s enough for me to fully endorse it as more literary. I really think it is its own thing, and even phrasing it as existing ‘between’ may be misleading. Perhaps it would be more accurate to describe it as existing outside both visual and literary arts. For me, my interest in other mediums is once again a return to the focus on ideas – Save The Date is a film because it’s a story I either couldn’t or didn’t want to make as a comic, and there were emotional moments that could be shown on screen in a way that couldn’t be repeated in comics. At the same time, I’ve only become less and less interested in the idea of adapting Clumsy into any other form such as film.

Ultimately, what if any personal or philosophical importance do you assign to the admission of your own work into the world of fine art? For example, A Matter of Life (2013) has been called “hilarious” and “profound” and a “joy to read” but is that enough (i.e., does answering the further question as to its art status tells us something (non-trivial) about the work)?

If the goal of the artist is to communicate ideas to people, and the inclusion of comics in galleries or museums, or seeing graphic novels receive higher literary esteem, can bring the work to a wider audience, I feel that is important. Categories change, the importance of this or that designation changes, and so it’s something that I don’t feel is of huge philosophical importance to the artist, unless that artist is specifically interested in those questions of definition. Personally, though, the reception of my work is something that becomes rewarding and encouraging, even inspiring, and would be important if only for the impact it has on how proud it makes my parents.

Some criticized Clumsy (2003) as being too darling and overly sensitive. You answered back with the devastatingly biting reply: Be A Man (2005), in which you recreate seminal scenes from Clumsy that replace you with your hyper-masculine dude-bro doppelganger. Be a Man is a possible Clumsy, retold from the imagined perspective of a possible Jeffrey Brown, namely one who is a ultra-macho, insensitive oaf. Understood that way, Be a Man strikes me as being in a meaningful sense no less revelatory than Clumsy. It also hints as other possible retellings: Clumsy retold from the (as imagined by Jeffrey Brown) perspective of Theresa, Unlikely from the (as imagined by Jeffrey Brown) perspective of Allisyn, AEIOU from the (as imagined by Jeffrey Brown) perspective of Sophia. Just like Be a Man, such retellings might plausibly thought to remain at least obliquely autobiographical in nature, and in some cases involve no more or less distortion of time and memory than their more straightfowardly autobiographical counterparts.

At its base, Be A Man is really just a joke – the title comes from an actual line in a review telling me that I needed to just “be a man”. This was really interesting to me on multiple levels. First, that there was a lot of response to Clumsy that was not about criticism of the book, but of the characters in the book, to the point where the only thing they were commenting on was my character, when really all the book shows is one particular period of my life, and really a limited view of myself as a person, and although the book used my life to construct its story, my life wasn’t really the point. Second, the idea of what a “man” is or should be seemed like a very silly thing to be talking about with absolutely zero indication of what they actually meant, any supporting evidence as to why their viewpoint was valid, or why their particular idea of manhood was better than any other idea of it (and better how – better to continue the spread of their socio-political ideals over those of someone else? better for the survival of the human species?). After I wrote Be A Man I realized there were a couple things in the book that I had done at one point or another. Clearly, if I could think those things, they’re part of me on some level, no matter how civilized I manage to be, or how much I’m able to suppress those thoughts in favor of more socially acceptable ones.

Do you think there to be a moral dimension to autobiography, especially with respect to the portrayal of those whose lives intertwine with your own?

I don’t think it’s inherent to the medium – exposing someone else’s story (or secrets) isn’t inherently immoral, and doesn’t necessarily make the author a jerk. That said, I have a host of self-imposed rules when I work with autobiography. I try to not make anyone else look any worse than I do – I really try to show that I’m just as, if not more, flawed. There are certain things that I won’t right about out of respect, although where crossing that line occurs changes from person to person, I suppose. I very much avoid ever writing something for another purpose – trying to win a girl back, trying to apologize through a story, trying to assassinate someone’s character just because I was angry, or to intentionally hurt feelings with something I write about, or more accurately, how I write it.. I try to write things in a way that the people I’m writing about understand that in the end, the work isn’t about them, or ‘us’, but about relationships and young love and life, and hopefully I’m not sacrificing their stories too much or that the potential benefit to a wide audience seeing these comics outweighs any hurt I may have caused.

How might this moral dimension of autobiography potentially conflict with its artistic dimension (both more generally and specifically with respect to your own work)?

It’s a fine line to walk, trying to put everything in that the story needs without stepping over a line that could destroy someone emotionally, especially someone I cared so much about. I try not to compromise, but there are certainly times I could’ve included things that would change a reader’s view of someone in the autobiographical comics. Whenever it’s something I start to feel I might regret later, or something that would feel really wrong, I question how necessary it is, what purpose does it serve, is there another way to get the idea across. It’s not an exact science. It’s a lot of time just thinking about things, and trying my best to be fair to everyone involved.

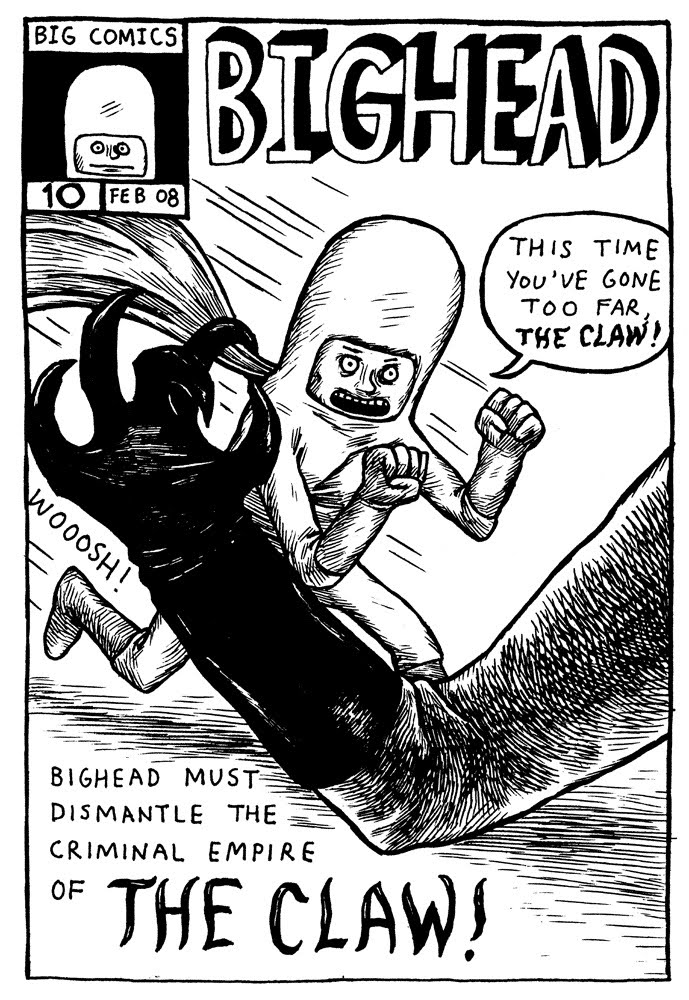

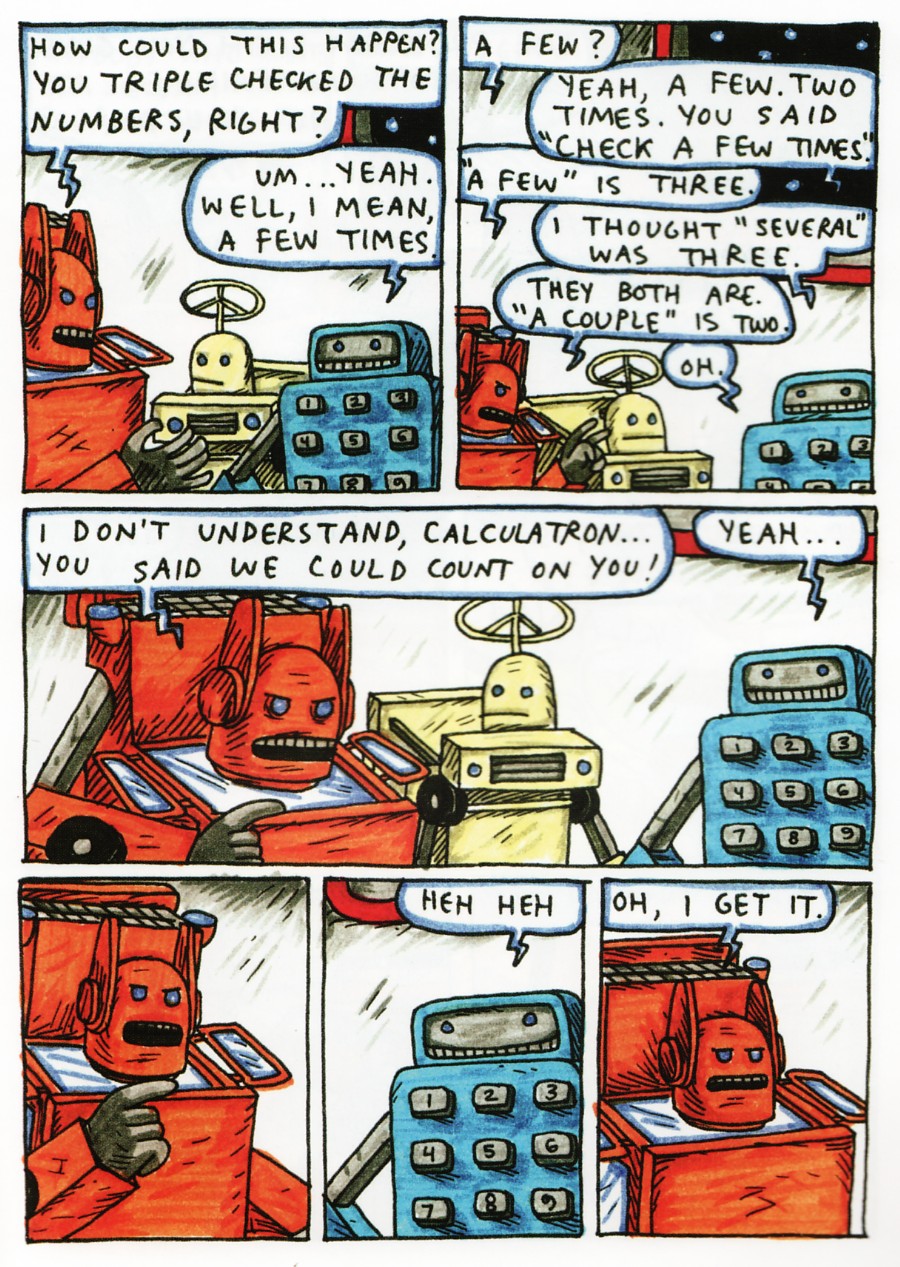

Your parody work, especially Bighead and The Incredible Change Bots, skewers to hilarious effect those superhero comics and toy-shilling cartoons many of us devoured in our youth by sending up their exceedingly tired and hacky tropes with an impressive (and surprising) level of sophistication. For these works, what do you take your relationship with the audience to be? That is, in order for an audience to fully/properly appreciate either Bighead or The Incredible Change Bots must that audience stand in much the same nostalgic/realistic relationship to the source material as do you?

I like my comics to work at multiple levels; I think with the Change-Bots books there are a lot of specific jokes or extras that add to the reading experience if you grew up watching the Transformers cartoons, but you don’t need those to appreciate them, or to find them funny. In the same way, there’s a decent amount of innuendos or more adult jokes that kids won’t necessarily get the subtext of, but can still find funny on the surface. I think the nostalgic relationship helps me in making those books, because there’s a familiarity and fondness that allows for a close reimagining without resorting too much to cliché or obvious, easy jokes. So hopefully if the reader has the same relationship to the source material they’ll get more out of it, but it’s not a requirement for a reader to enjoy them.

Does the notion of a proper or target audience play a role for your parody work in a way it might not for your autobiographical work, especially given the radical tonal shifts between them: e.g., Bighead (2004) follows Clumsy (2002) & Unlikely (2003), Incredible Change Bots (2007) follows AEIOU or Any Easy Intimacy (2005) & Every Girl is the End of the World for Me (2006)?

I think it’s important to consider audience, and it’s even okay to have an ideal audience in mind, but I’m very wary of the limits that come with a target audience. I prefer to make the work fit my vision and then let it find its audience, or figure out the audience as I develop things. In a way I’m ultimately just writing for myself, and I’ve just been lucky that these books have struck various chords with readers the way they have. It’s also an ongoing process, the more books I write, and the more I see how people respond to them, and the wider the audience they reach, the better sense I have for who will be reading things I’m working on and how they’ll respond. As for tonal shifts, I think they seem more radical than they are in reality. The autobiographical comics are much goofier than the heartbreak subject matter leads people to read them as, and there are plenty of emotional moments packed away in the robot stories, that would fit right in the autobiographical comics with just a little reworking. Like taking away the robots.

What about for your recent best-selling work set in the Star Wars universe: Darth Vader and Son (2012), Vader’s Little Princess (2013), Goodnight Darth Vader (2014), Darth Vader and Friends (2015)?

I think the Star Wars books – both the Vader series and my middle grade Jedi Academy series – are actually a pretty integrated combination of my more humorous parodies and my autobiographical comics. Aside from the fact that I grew up with Star Wars, Vader and Son is basically about my life as a parent of a four year old. Luke is even drawn just like I draw my son Oscar, except Luke gets the 1970’s haircut. Likewise, Jedi Academy borrows directly from my middle school years, both in general emotional terms of being awkward, and in specific events. The Jedi Academy series is specifically targeted toward readers ages 8-12, but I write it pretty much the same as I write any of my autobiographical comics, and the only difference (aside from the Star Wars aspect) is changing the language for that age group, and occasionally removing a concept that might be a little advanced for kids, or something they wouldn’t appreciate, though it might be within their understanding. I did have a fairly specific audience in mind when I wrote my first Star Wars book, Darth Vader and Son – people like me who had grown up with Star Wars and were now having kids of their own. I still tried to make it not so specific, so that parents could still enjoy it even if they weren’t Star Wars fans, and if you were a Star Wars fan you didn’t have to be a parent to enjoy it, and if you were a really hardcore Star Wars fan, there’d be lots of little jokes and things that would add even more to the reading. That worked well, and the one thing I didn’t anticipate for audience was how much kids have liked the books. I did also try to make the books kid-friendly, so there’s no joke that’s too adult and it’s naturally visually appealing, but I don’t think I could have reached a wider audience with the Vader books if I tried.

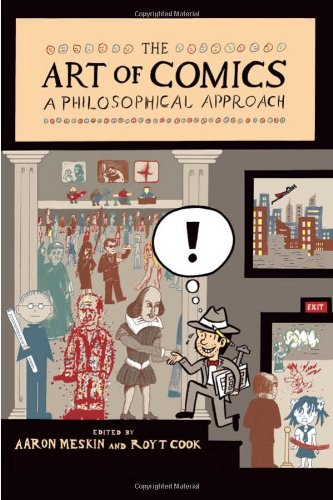

Finally, in the last 10 years or so, comics have received increasing amounts of philosophical attention, most recently in the Roy T. Cook & Aaron Meskin volume The Art of Comics: A Philosophical Approach (Wiley-Blackwell, 2012). There is of course a sense in which being a target of philosophical enquiry validates the artistic merit of the medium. However, some might see this validation as coming with price, signaling the end of the medium, artists, and the practices therein being driven by an organically developed and fully internalized theory of comics and the beginning of the medium, artists, and their practices instead being shaped by a synthetic, externalized, and fine-art modeled theory of comics imported by philosophers (analogous to having the significance of your city-state validated by its being sacked by the Visigoths). How do you, and how do you think other comic artists, view increased scrutiny by Philosophers of Art?

Personally, I’m not worried at all, although I do feel like some cartoonists may be a little bothered, as if removal of low-brow status and DIY ethos will somehow dilute and ultimately negate the potential of comics to be truly expressive. At the same time, I don’t think most artists, myself included, feel that our work needs any kind of validation to be considered successful. I certainly have never felt that I needed mainstream culture to accept geekdom to justify my love of Star Wars, and the fact that Star Wars can be co-opted by such a wide range of people, companies, and products doesn’t adversely affect my love for the movies. So as a cartoonist, I don’t feel that increased philosophical attention to the medium should necessarily have any negative effect on the creation, as my focus will remain pointed at the ideas I want to express and finding the best way to communicate those ideas. Even if I feel like, at this point in time, the framework for the criticism of comics is something that is maybe being applied to the work rather than becoming a structure upon which new comics work can be built in interesting or different ways, I think overall that the more people looking at comics, and the wider variety of viewpoints, experiences, and agendas people are bringing to their readings of comics, the better off comics will be. Ultimately, if comics are going to continue to move past their basic origin as fluff entertainment (or, if not origin, the common perception for the majority of the medium’s existence), they will need people like philosophers taking a closer look at their mechanics and nature.