What follows is a guest post by Rebecca Victoria Millsop. Rebecca is a fifth year PhD student at MIT writing her dissertation in the philosophy of art. In the not-so-distant past she worked on issues in philosophy of logic and mathematics and, while she found this incredibly fun, she believes that working on issues in the philosophy of art will make more of an impact on the world. She also lives on a sailboat in Boston Harbor, paints, and volunteers for a non-profit art organization in Boston, HarborArts.

It’s been a while since painting was first proclaimed dead (apparently it was French painter Paul Delaroche in 1835), and ever since then there’s been a lot of ink spilled (and words typed) about whether or not it is dead, is dying, or never died in the first place. The consensus has shifted throughout the years, and, at least recently, the jury seems to be out (okay, the jury, at this time, thinks that painting is dead, but just by a little!):

Regardless of what the critics and headlines say, paintings are still created, put on display in museums and galleries, bought and sold… so there are folks that still care about painting. When asked about the supposed problem of painting, painter Amy Sillman responded “What’s the problem? Painters don’t see any problem!”[1] Painters are still painting and people are still buying paintings, so painting isn’t dead, but a lot of folks certainly think that they need to justify painting regardless of its capacity to breathe. This need-to-justify really caught my attention when I went to visit a show at the Institute of Contemporary Art here in Boston called Expanding the Field of Painting last year. The show consisted of 25 works by contemporary artists who, according to the assistant curator Anna Stothart, “through their varied investigations into the history, present, and future of painting, acknowledge and often exaggerate its contradictions to proclaim that painting still is, and will likely remain, very much alive.”[2]Not dead!screams the show, SO not dead! The idea behind the show, from what I gather, was a demonstration of how contemporary painting is important, relevant, and valuable because it goes beyond painting. I, perturbed by this message, warily went around the gallery rooms and pointed at different works “This is a work of video art,” I said pointing at Alex Hubbard’s 2011 The Border, The Ship,

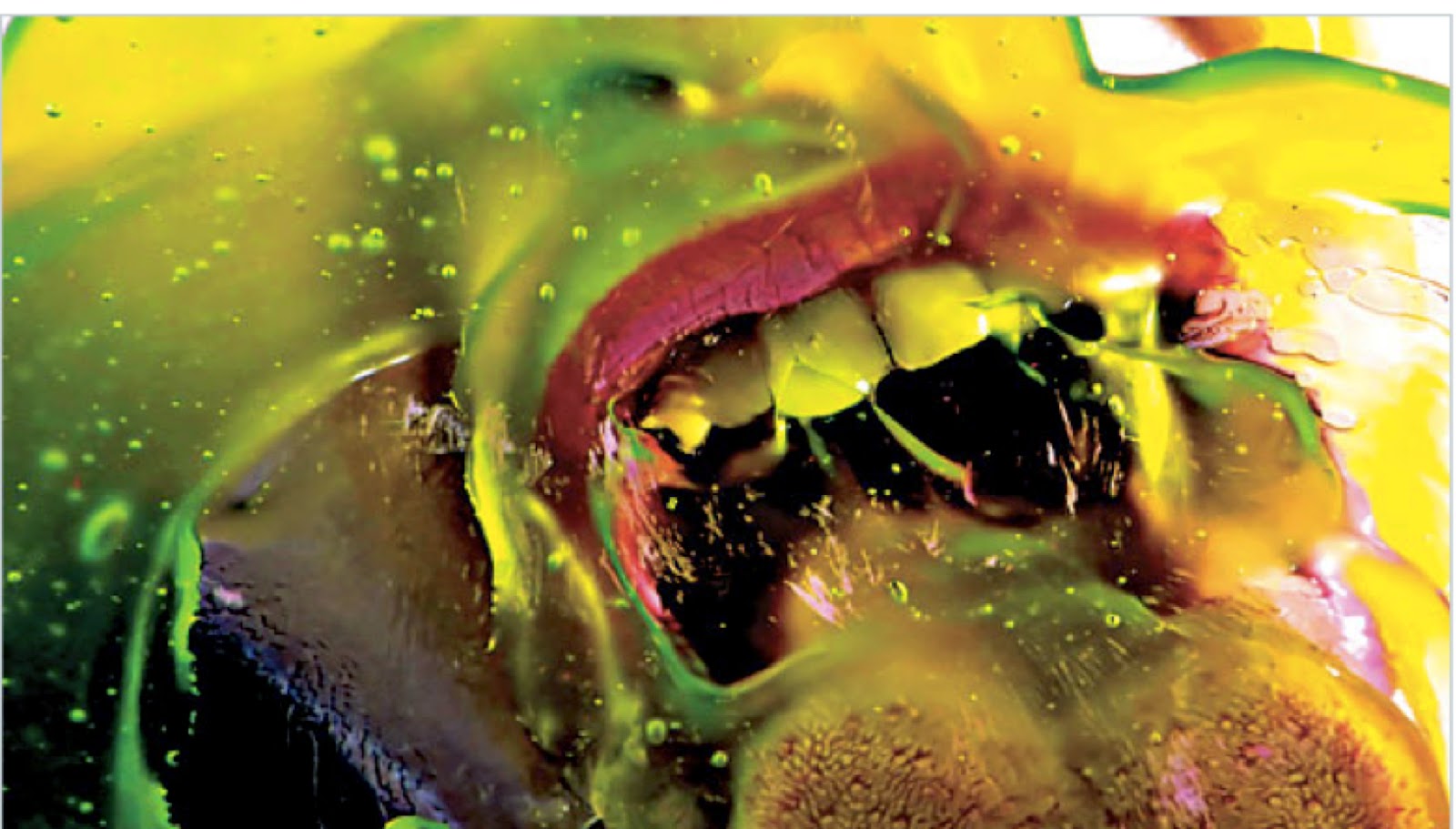

and then again when pointing at Marylin Minter’s 2009 Green Pink Caviar,

and “This is just plain old sculpture,” I said pointing at Nicole Cherubini’s 2003 Gempot #3 with Fur,

“This is photography,” I said pointing at prints from Pipilotti Rist’s 1998 Remake of the Weekend,

… and so on.

The problem with the show stems from the fact that a considerable amount of the work just isn’t painting. The works might be playing with or touching on aesthetic properties that are central to the nature of painting… but that doesn’t make them paintings! If I am getting the right message from the show, the conclusion I draw is that for a painting to have value, it has to be more than just painting.

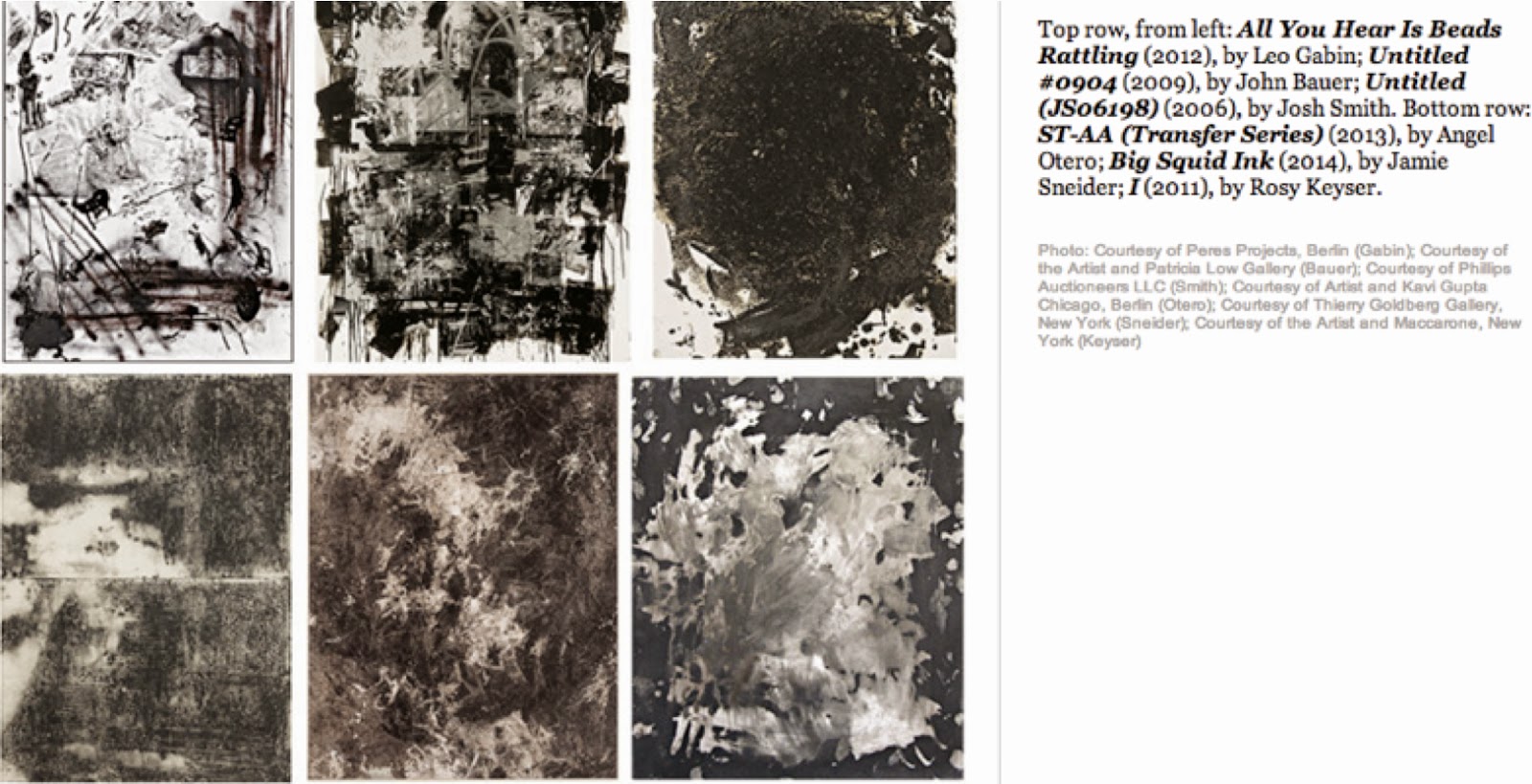

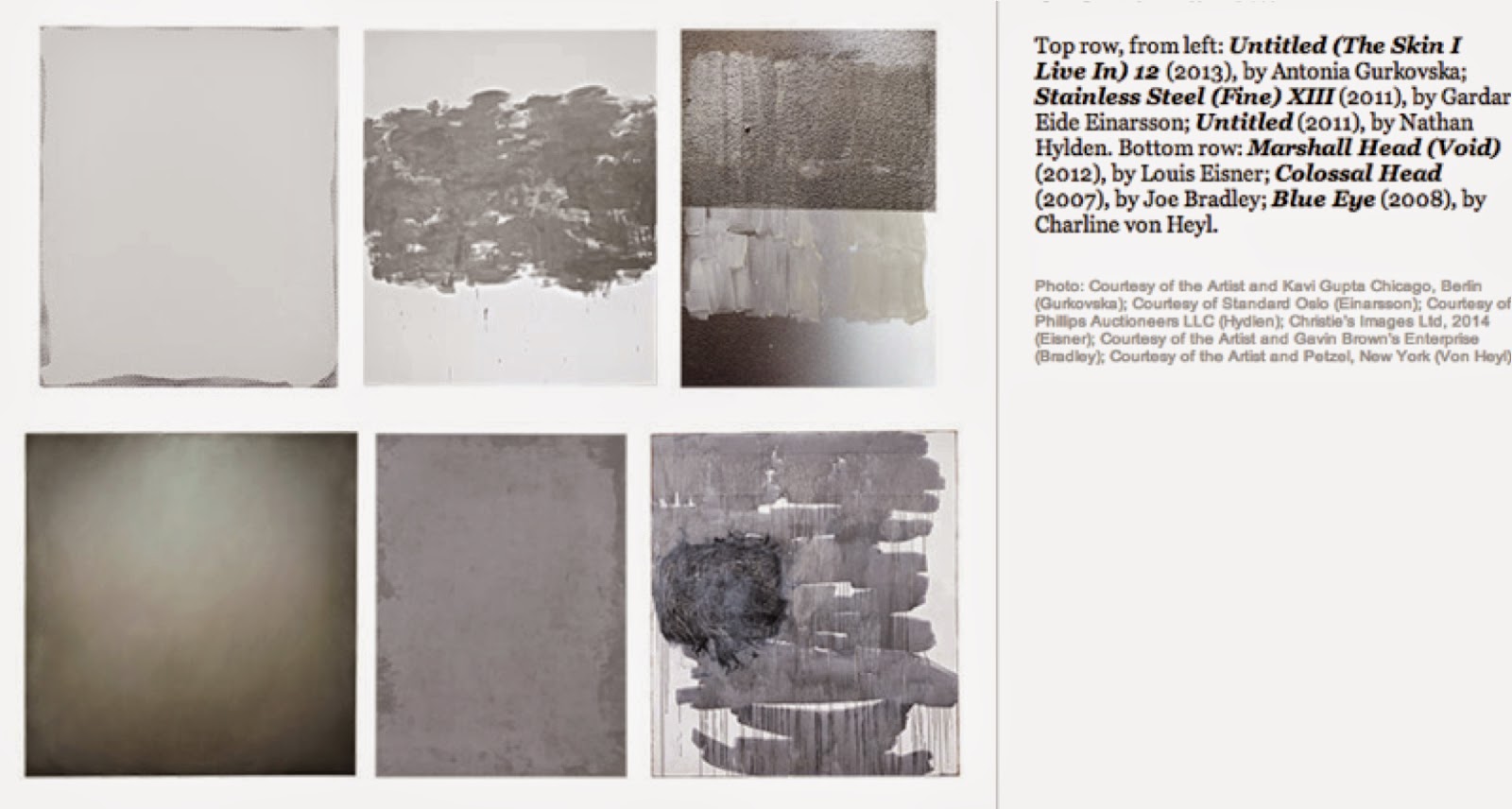

Shortly after my visit to the ICA, a friend of mine posted an article to facebook written by the oh-so-lovely Jerry Saltz titled “Zombies on the Walls: Why Does So Much New Abstraction Look the Same?” The main gist is that the market is saturated with unoriginal canvases that are pleasurable while being devoid of meaning. “Galleries everywhere are awash in these brand-name reductivist canvases, all more or less handsome, harmless, supposedly metacritical, and just ‘new’ or ‘dangerous’-looking enough not to violate anyone’s sense of what “new” or “dangerous” really is, all of it impersonal, mimicking a set of preapproved influences.” Check out the slideshow for some examples.

Although I get his point and the examples given certainly make a viewer think geez I can’t believe people get paid to make these!, the emotions I felt after reading the article were interestingly connected to those I felt at the ICA show. The ICA show implies that everything has been done and in order to be an interesting painting, it has to go beyond what has already been done. The paintings discussed in the Saltz article aren’t original in any way, they are simply pleasurable to their audience. And that’s not okay, says Saltz. In order to have real value, a painting must be new and different from other paintings out there. Hence, the ICA show. But, why can’t these canvases, although similar, have value because they are bringing aesthetic pleasure to the individuals buying and enjoying them? What about the pleasure brought to the artists who paint them, as well as helping them earn a living?

Alright, so before I continue with my rant I should put all my cards on the table. I am a painter, so I have a stake in this whole ordeal and, beyond that, I’m a non-representationalist, abstract painter, so I’m potentially guilty of creating a few of those meaningless zombie paintings…

Despite these important biases, I think that what bothers me comes from a less personal place: the art world has fetishized originality as an aesthetic/artistic value, and, further, this is problematic because other aesthetic and artistic values are placed on the back burner, resulting, often, in obscure work that is less accessible to many viewers. Originality as an important aesthetic value has been discussed and debated in the literature over the years; some rank it among the highest of aesthetic values (Wollheim, for example), while Beardsley claims that “originality has no bearing upon worth: a work might be original and fine, or original and terrible.”[3]

From all the different conclusions drawn on the subject, I find that Sherri Irvin comes to a helpful one in her 2005 paper “Appropriation and Authorship in Contemporary Art”: “there is nothing in the nature of art or of the artist’s role that obligates the artist to produce innovative works. The demand for originality is an extrinsic pressure directed at the artist by society, rather than a constraint that is internal to the very concept of art.”[4] To a certain extent, this pressure for originality is understandable; the audience hopes that a work of art will take them to new levels of understanding and, often, this occurs through new experiences caused by things the audience has never seen/heard before. But this begins to become a problem when individuals with incredibly buffed up art history backgrounds complain that works lack meaning because they are similar to works made in the past. A lot of people may not know about those other works, and they may have an incredible experience with that “unoriginal” work that means a lot to them. The demand for originality can force artists to move above and beyond what has been made in the past simply for the sake of moving above and beyond what has been made in the past. This can lead to really brilliant works of art but, often times, it can lead to obscure works of art that require a lot of art historical knowledge to even approach, let alone understand or appreciate. People have been painting for a really long time and there are a bunch of folks that know a lot about its history; these folks are often the ones writing the reviews, critics, and articles that demand painting to justify itself by being something more than painting.

To my surprise, I found that the contemporary painting show that just opened up at MoMA (the first painting-focused show in 30 years!) doesn’t give into the need to justify painting by making it something more than painting. (Granted, I haven’t seen the show in person yet, but I do have the show’s monograph!) The show is titled—yes, it’s a bit silly—The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World and it consists, completely, of objects that are obviously paintings.

Pictured above, descending: Richard Aldrich. Angie Adams/Franz Kline. 2010–11, and Amy Sillman. Untitled (Head). 2014.

The curator, Laura Hoptman, discusses the atemporal artist as one who creates works “of art that refute the possibility of chronological classification, [this] offers a dramatic challenge to the structure that disciplines like art history enforce—the great ladder-like narrative of cultural progress that is so depend upon this idea.”[5] Thus, the atemporal artists in the show are embracing their place as painters in the art historical narrative by giving up on the importance of making something completely original—i.e., a painting that is a video or a photograph, like those shown in the ICA show–that makes them stand apart from that narrative. They are working within it or, perhaps better said, with it. The artists in the show make beautiful, engaging, meaningful works that are obviously based on the work of past artists, and they aren’t making any apologies for this.

Pictured above, descending: Dianna Molzan. Untitled. 2009, & Oscar Murillo. 7+. 2013–14.

Hopman is using the word “atemporal” as it was introduced by William Gibson in 2003 to described “a new and strange state of the world in which, courtesy of the Internet, all eras seem to exist at once,”[6] and I think it’s worth noting Gibson’s own views on the value of originality in a tweet a while back: “less creative people believe in ‘originality’ and ‘innovation,’ two basically misleading but culturally very powerful concepts.” For all of the heady, jargon-y language that Hoptman uses in the essay accompanying the show, I think there is a simple, important message once can draw from the show—one that is neatly tied to Gibson’s tweet: a work of contemporary art necessarily sits within a vast art historical web, but we don’t need to judge the art against that web by seeing if the work is more or less similar to it, rather we should consider how the artist works with that historical web to make a moving, meaningful, engaging work of art. I love this message because it does challenge the fetishization of originality that plays an important role in the “great, ladder-like narrative of cultural progress” that Hopman discusses in her essay; focusing less on the never done before and more on the aesthetic or experiential value of the work will lead, I believe, to artists focusing more on making solid works, rather than trying to do something that’s never been done before simply for the sake of being original. A painting doesn’t have to actually be a video to be engaging, just as a painting that takes on the qualities of many past paintings can be meaningful and engaging.

These conclusions, I believe, could open the door for more accessible works of art or, perhaps, the acceptability of accessing a work of art without a degree in art history. Those super-original works of art are often those that push the boundaries of what is considered to be art for the sake of being original, and most of the time the only folks that can appreciate these works are those with an extensive art educational background. With the focus on originality many individuals without said educational background don’t even want to try and experience those works. The fetishization of originality has not only lead to painting needing to be more than painting, but also to the disengagement of a broader audience with contemporary works of art. Pushing the boundaries for the sake of originality often results in pushing away a potentially interested and engaged public. In the end, I don’t know if atemporal art is the savior, but I do think that the show at MoMA isn’t trying to justify painting, instead it celebrates the ability of painting as painting to remain impactful and engaging in the contemporary now.

[1] “Painting Beyond Itself: The Medium in the Post-Medium Condition.” Participants who cited “the problem of painting” included art historians Benjamin H.D. Buchlqh and the critic Isabelle Grew.

[2]http://www.icaboston.org/exhibitions/exhibit/ICA-Collection-Expanding-the-Field-of-Painting/

[3] Beardsley, Monroe. Aesthetics: Problems in the Philosophy of Criticism, 460.

[4] Irvin, Sherri. “Appropriation and Authorship in Contemporary Art.” British Journal of Aesthetics 45 (2005), 137.

[5] Hoptman, Laura. The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2014. Published in conjunction with the exhibition of the same title.

[6] Reynolds, Simon. Retromania: Pop Culture’s Addition to Its Own Past. New York: Faber and Faber, 2011.

February 4, 2015 at 4:12 pm

I think your spell-check changed ERAS to EARS

February 4, 2015 at 5:02 pm

Welcome to the Aural Singularity: You Can't Help But Hear Me Now!

February 8, 2015 at 12:38 am

Let me give a few thoughts which may or may not be relevant, because I'm not entirely sure I follow you.

1. Is it really the case that painters are beholden to this totally insane notion of originality? Because it really is rubbish, and people've been saying so at least since 1938 (Collingwood's 'Principles of Art' has a fair bit to say on precisely this) and possibly much earlier (I have a dim recollection of Croce making the same point); but it can't be much earlier, of course, because the notion that originality might be an end in itself doesn't really go back before the twentieth century! And it's not just philosophers in their introverted academy either: my ear is to the ground of twentieth-century music (or so I fancy), and although there was a bit of this rubbish – arguably! – going around in the one or two decades after WWII, I can't think of anyone who espouses this kind of thing. Of course there have been people who've been radical, but never, unless I've forgotten something, has a composer worth remembering been radical just for the sake of it.

2. Assuming you're right about painting, this needs explaining. One explanation occurs to me: I remember someone saying once (some professionally arty person) that the rise of three-dimensional paintings has rendered it impossible for the two-dimensionality of other new paintings to be unthematic, and so for painting to exist. In other words, the two-dimensionality always has to be a choice; but for someone to work in three dimensions is surely for them to work in sculpture; and so contemporary painters are working in three dimensions even when their canvas is flat, and so they are all sculptors. Now, assuming this is right – which I would dispute, but painting isn't my thing so I dunno – it looks like painting is facing an existential crisis deeper than anything sculpture or music or literature have to face. Perhaps originality is particularly called for in such circumstances? I confess I'm not sure how the argument would go, but the 'atemporal' response certainly won't work, if I understand it aright.

3. Another problem I have with what I take to be the 'atemporal' position – and this may be more a matter of whether it (or even the term you use to label it), like 'originality', is misleading, rather than whether it is 'correct' (all of these terms are historically situated calls to action, so talk of 'correctness' is, I suspect, out of place) – is that there are robust senses in which we exist at/in a certain time and have to deal with that fact. It is obviously unacceptable, not to mention impossible, for the reasons Borges gives, for us to paint like Rembrandt did. And you say this, sure: but let me go further, and say that we have to deal with the fact in a way which is original, because those earlier in the tradition do not live in/at the same time. So how, I wonder, can you give due importance to originality? It's not enough to say that your theory allows for it, because this is politics, and you have to not just allow for what's important but include it in your manifesto; nay, in your battlecry.

4. There's nothing wrong with creating art for the sake only of those who are art experts! Although I agree that we should be careful, and that if all art is such art then there's a big problem somewhere.

February 8, 2015 at 12:39 am

Damn, that was supposed to be anonymous. Well, no harm I suppose. Pretend you don't know who I am.

February 9, 2015 at 7:41 pm

Aah damn, I just wrote a long response and the internet ate it!

oh well, to sum up:

-what is paint?

-you start to get in referencing the two painting shows, but I'll push that the dialogue is largely advanced by a flooded competitive class of curators.

-should and, more importunely can we talk about painting as anything other than a tradition and trajectory? (when does a lump of material start to become painting and is it a helpful distinction?)

-what is closer to what? cave paintings to takashi murakami, or takashi murakami to brakhage?

thoughts provocation!

and i agree with james's #4, and as a philosopher i think you might relate.

hope to see you around before long,

cheers

bjorn

March 4, 2015 at 5:54 pm

OMG I just realized there are comments on my post! I will respond ASAP. Thank you so much for engaing with my ideas!