Artist Curtis Gannon interviewed by Christy Mag Uidhir

Curtis Gannon (b. 1974) completed his undergraduate studies at the University of Houston, and then received an MFA in Painting at San Diego State University. Using American action comics as source material, Gannon creates collages, sculptures and installations that reference the Pop language of the medium and its influence as a universal form of visual communication. Gannon’s works have recently been exhibited at Blaffer Gallery, Museum of Fine Arts Houston, Williams Tower, and Lawndale Art Center. Gannon lives and works in League City, TX.

The world of fine-art was introduced to comics most notably in the 1950s and early 1960s when Pop artists seeking to challenge traditional notions of fine art began appropriating the panel images from comics: e.g., Warhol’s Saturday’s Popeye (1960) and Superman (1961) as well as Lichstenstein’s Image Duplicator(1963) from Uncanny X-Men and Takka Takka (1962), Bratatat! (1963), Whaam!(1963) from All American Men of War. Of course, this was done in such a way that inevitably divorced the appropriated (and often de-paneled) images from the narrative they were supposed to serve. Your work, however, shifts the focus away from what at times can be a condescending fine-art fascination with comic imagery along with the often crude narratives it serves and instead draws attention to the very structure of comics itself—i.e., not its pictorial or narrative content but its formal content.

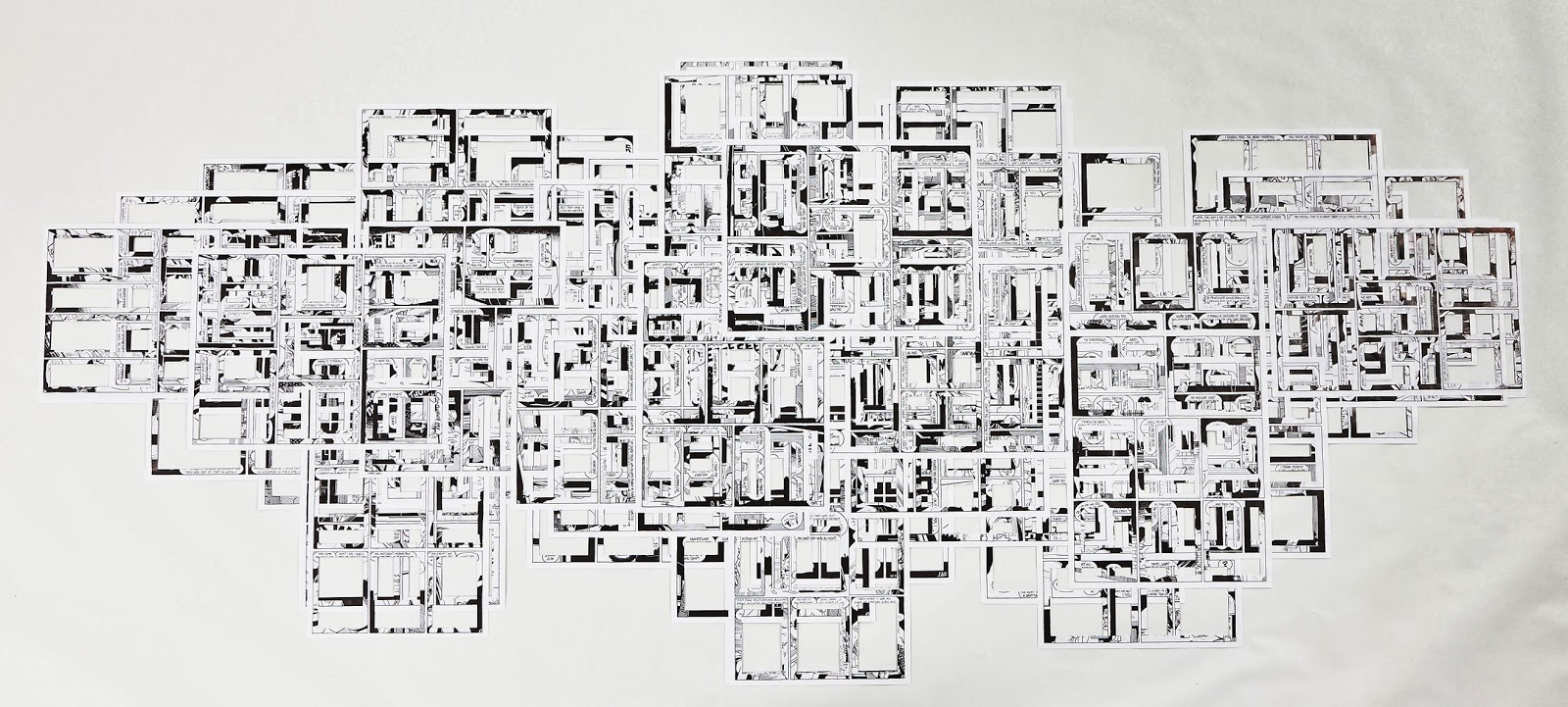

Paper Installation 12 x 6ft diameter (dimensions variable)

Of course, from the fact that comic imagery and now comic form should be counted amongst the legitimate subjects for works of fine art it doesn’t follow that comics themselves should be similarly counted amongst the legitimate works of fine art. As an artist who uses comics and comic imagery to create artworks about comics but not themselves comics, where do you stand on the fine-art status of comics (or on the commercial-art/fine-art distinction in general)?

Like any mass media form of entertainment, the highest achievements of the medium have the potential to be elevated to the status of “fine art”. In my opinion, there is an art-to-crap ratio of 10%-90% in most forms of entertainment. A rare minority rises above the common to a level of what might be considered “art”. Comics that should be considered fine art are those that set the standards of quality and form. New approaches to sequential narrative and storytelling, and pieces that challenge preconceived notions about comic book content, are more than entertainment. They make us question what comics are and how they function. Cultural objects that question society and culture, or test the commonly accepted ideas of a medium and its function, meet the criteria for what is often considered art in any form.

Comics were not initially created as art, but to be inexpensive entertainment, readily consumable and disposable. In a similar way, many objects in museum collections today were originally created to educate, document, or entertain as objects of beauty.

Plexiglass 32 x 41.5 x 2in

Do you think comics can be appreciated as fine-art while still being appreciated as comics?

Absolutely. When I read comics like Nemesis, Punk Rock Jesus, Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, or even Fantastic Four #1, I enjoy them not only for their narratives, but for their interplay of text and images in their entirety. Unfortunately, when displayed in institutions, a comic is often shown out of context by exhibiting it closed, or opened at some predetermined point within the text. Much like cinema, a comic book must be experienced from cover to cover in order grasp the creator’s original intent.

New approaches to storytelling, character development, and illustration techniques set some iconic issues apart from their forerunners, elevating the genre to new heights. I believe these are works of art not only for their physical beauty, but also for the experience created through sequential narration. They cause me to question the comics that were created previously, and set a new standard for all of those created afterward.

Collage 32 x 66 inches

What if anything do you think would likely have to change for comics to gain admission to the world of fine-art?

Time is the major factor when considering if an everyday object is “art”. Once objects become rare because of the passage of time, they are often considered valuable. An appreciation for an object also increases when seen in retrospect, acknowledging how that object was a reflection of the attitude of its time, as well as its effects on culture and its own medium. For example, Action Comics #1 is important for two reasons: it essentially established the “super hero” comic book as a genre and because so few exist today. Surviving issues are therefore extremely valuable as objects.

Collage 84 x 96 inches

What sort of reactions from the fine-art community have there been to your work with respect to comics as its material and subject matter?

I get some mixed reactions from the fine art community about my use of comics. For the most part, it isn’t an issue. Comics have now become accepted (after 100 years) as an important document of popular culture. They reflect on who we were and who we hope to become. The relevance of comics has been established among academia as well. They are recognized as fertile material for understanding and commenting on modern urban culture. Most of the people I encounter who are resistant to comics have little to no experience with the medium. They have written them off without trying to understand them.

Collage 15.75 x 15.75 x 1.75in

Some folks within the comics community see Lichtenstein in a rather unfavorable light, namely as a fine-art carpetbagger guilty of flagrant theft who enjoyed wealth and fame as a result while the comic artists from whom he stole were largely consigned to obscurity and poverty. Do you see your own work as a species of appropriation and if so to what extent if any do you think appropriation of a comic’s page structure (panelation, guttering, etc.)—rather than it’s pictorial elements—susceptible to similar charges of fine-art carpetbaggery?

My work is a form of appropriation in two ways. In a simple way, I am recontextualizing the comic book page as a media construct that facilitates sequential narrative. For this purpose, a page from any comic would be suitable.

However, for me as an artist, I don’t want to use just any page. The sources that are repurposed in my work are very carefully selected. My work is a tribute to my favorite creators, in much the same way as a musician would cover a song by another artist. I want to dialogue about specific comics I loved as a kid, as well as comics that are hallmarks of the medium itself. I am continuously in awe of the works of Stan Lee, Claremont, Kirby, Ditko, Miller, Romita, Byrne, and Mignola (to name but a few).

Collage 20.25 x 12.25 x 1.5in

In this more complex way, I want my work to be a homage to their accomplishments by representing these comics in new ways; hoping to attract non-typical audiences to re-evaluate the original sources. The comics I adopt are not inert documents of the past, but are viable works that are the spring board for new ideas and discoveries. When I give talks about the work, I find myself spending much of my time referencing the original sources and why they are important.

Paper Installation 56 x 48in (dimensions variable)

I understand why the comic book community frowns upon artists like Lichtenstein and Warhol. The images they appropriated for a small part of their careers helped to make these artists famous without specific reference to the original creators. But a major point is often over looked by these critics. The work of these and other Pop artists made major strides in establishing comics as a legitimate artistic medium to academia and society as a whole. They helped to raise comics out of the perceived mire of mass media “low culture” to a unique and important form of literature as well as art in their own right.

Both of these viewpoints will continue to have countless supporters, but that is how I perceive it as an artist and a lifelong comic book fan.

Curtis Gannon is represented by THE MISSION Chicago | Houston (www.themissionprojects.com) For more information contact Sarah Busch, Director | Houston: (713) 874-1182.+