What follows is a guest post by Alexis Shotwell (Carleton University).

Did you know that Fifty Shades of Grey started its life as an erotic fan fiction of the Twilight novels? E.L. James changed the names for the publication of her series, but Anastasia is Bella, Christian is Edward, etc. Fan fiction is when readers (“fans”) write stories set in fictional worlds created by other writers. Now, I don’t need you to be excited about vampires or kink, separately or together. But if you didn’t know Fifty Shades’ origin story, isn’t it interesting to learn that it is part of a longer conversation? When I learned this, I suddenly perceived the books as an interaction rather than a proclamation, a work of collective enthusiasm rather than an individual project.

In art or life, we can be part of an unfinished, collaborative process of creating something that doesn’t yet exist out of what we receive. We can do that with wonderful things, but also we can do it with the lousy, complicated, terrible things that make up so much of our world. People joyously and prolifically generate new work even in the face of despair, and we can too.

The aliveness of the reader

Roland Barthes’s essay “The Death of The Author” formulated this idea: The author does not determine the meaning of their writing. Barthes says that to reduce the text to what the Author intended, or focus on what the Author thinks or does in their non-book lives, is to “impose upon that text a stop clause, to furnish it with a final signification, to close the writing.” From this approach, writing something is an opening – as the author finishes their work, we readers take it up and make meaning with it. Barthes writes: “refusing to assign to the text (and to the world as text) a ‘secret:’ that is, an ultimate meaning, liberates an activity which we might call counter-theological, properly revolutionary.” So the author is always involved, but they do not furnish the ultimate meaning of a work or world. The original author is not a god, the only being who can decide what happens in their world. People who are simply reading and finding nourishment in a text participate in this kind of open reading. Every time I have the experience of reading something that resonates with my life or gives a new understanding to my experience, I’m also doing this kind of revolutionary reading, where things that are given to me are available for transformation. But perhaps this kind of transformative, open reading is most obvious in practices such as fan fiction.

Fan fiction

You may think of fan fiction as a small niche hobby, if you’ve heard of it at all. But there is a dizzying array of work available on sites like Archive of Our Own and FanFiction.net, where people write and share work out of love for a world that they did not originate but that they contribute to creating. While fanfic often has erotic content, much is kid-friendly. Writing fanfic always also involves reading it, and participating in a community that jointly shapes the interpretive context of shared texts. Fanfic is a beautiful exemplar of a more general approach to making art and offering it to others as a practice of craft abundance. It refuses the idea that we should monetize everything creative that we make (Fifty Shades’ commercial success is a real outlier). It makes a claim on shared worlds that some original authors are not comfortable with (Stephenie Meyers reportedly decided not to write a book from Edward’s point of view on hearing that E.L. James was doing one from Christian’s). Most interestingly, it eschews the model of the brilliant Author, spinning worlds out of whole cloth, isolated and mighty. Instead, writers of fanfic are self-avowedly both consumers and creators of work — fanfic exemplifies one way that works of art offer us worlds unpredicted by their own authors. It demonstrates the aliveness of readers as also creators, in Barthes’ terms, “refusing to assign to the text (and to the world as text) a ‘secret’.”

Critique as love

Consider how often we’re told that there is a secret, ultimate meaning to the universe, and that our job is just to discern it. Self-help writer and artist Marlee Grace puts it like this: “Yes, it took until chapter 10, but I am here now to tell you the universe has a divine and specific plan for you. And it’s so magnificent. But we only get to have it if we pay very close attention. Here are suggestions for how to do so” (Grace 134). A lot of self-help books have this kind of approach. But if the universe has a plan for you, if everything happens for a reason, then the project is just to discern this plan – what Barthes thought of as a closed, pre-determined project. I object to this approach, and prefer the idea that we’re part of making plans for our lives. This is revolutionary (as Barthes puts it) because it assumes that we can change the script that has been written for us. We can have love for founding stories but still critique and transform them.

Critique as love helps us understand why we still feel betrayed when an author tries to be an Author, to close down the meaning of their text, or when they turn out to be a bigot (*cough* JK Rowling *cough*). The author is important to texts we love, and they can still hurt us even if they’re dead. The aliveness of the reader means that we can critique and enliven problems even in beloved worlds. This death and aliveness is an aesthetic situation; it invites us to practice our own capacity for response in a shared context. The meanings we make in relation to the work we engage are collectively and relationally crafted.

Writing our own stories in other people’s worlds

Jo Walton’s latest book Or What You Will (Tor, July 2021) offers a beautiful model for thinking about this kind of collective meaning-making. The main characters are a dying writer, Sylvia, and the main narrator she uses in her writing. He is alive, an invisible friend, a part of Sylvia, or perhaps a piece of life that slips into her fiction. Sylvia and her narrator have collaborated throughout her life, and he wants to find a way for her to not die through writing herself into her final novel. This novel-within-the-novel is set around and after Shakespeare’s The Tempest and Twelfth Night. If you ever wondered what Miranda, Caliban, Orsinio, Viola, and everyone else did after the plays — themselves arguably forms of fanfic — Walton offers an answer. In this book, they lived on, in a world that has defeated death. So did frequent visitors to Walton’s worlds Giovanni Pico della Mirandola and Marsilio Ficino.

Walton has for many books now offered the aliveness of story to people who lived in history (Plato, Ellen Francis Mason, and Socrates in The Just City novels; and Girolamo Savonarola in the recent Lent), in previous stories (warriors from the Táin Bó Cúailnge in her Sulien stories, faeries in Among Others), or in alternate histories (in the Small Change trilogy or My Real Children). She has long practiced with the difficult terrain of telling new stories that honour past stories while going beyond them. This book beautifully extends her career-long inquiry into the ways story can save our lives.

In Or What You Will, Sylvia’s mother was unloving, emotionally abusive, terrifying. Sylvia escaped her mother’s orbit, chewing off a paw to escape a trap, into a different kind of abusive relationship, a first marriage. Of that relationship, the narrator says, “The violence is the easy thing to talk about, in many ways. It’s much harder to say that he circumscribed her soul” (349). Sylvia is saved, or saves herself, freeing herself from abusive others who have controlled her life’s course. Here the book explores a question that follows from the death of the author: If others have had the power to write our story, what power do we have to revise it? When our very soul has been circumscribed, where do we find the aliveness to revise our lives?

Walton writes:

“There is a pernicious lie in Western culture that Sylvia has tried to combat in her books for years, and it is this: a child who is not loved is damaged beyond repair. Relatedly, anyone who has been abused can never recover. These lies are additional abuse heaped on those who have already suffered. … People who have been abused will not be the people they would have been if it had never happened. But they can be splendid people going on from where they are” (374).

The pernicious lie is propped up by a theory of selfhood positing the people who author us as having final say in who we are. But, this novel asserts, parents are not our gods and abuse does not write the whole story of our lives.

This exploration of people who have been abused, whose souls have been circumscribed by their parents or their partners, going on from where they are to be splendid people instantiates what Barthes thought of as resisting final signification, any secret, ultimate meaning emanating from the authors of our interpersonal experiences. It is taking our life as a text with some original authorship, but which we can rewrite. If we are sometimes characters in other people’s stories, subject to their writing, we are also our own readers, our own characters, our own authors, and because of our liveliness we can go on, making ourselves anew, no matter what history we inherit.

School shootings and parents-as-authors

Walton’s iterative exploration of the aliveness of the reader offers an immanent critique of dominant models of surviving abuse and interpersonal boundary violation. Sylvia’s mother was unloving, emotionally abusive, terrifying: What does that imply about who Sylvia can become? Walton contests the idea that abuse writes in stone what kind of life abused people can lead; she contests the idea that parents are our Authors and that they have the final word on our lives.

Contrast this with the commonsense idea that parents are responsible for their children’s behavior, especially in limit cases such as mass school shootings. In these narratives, abuse is taken to explain sociopathic, violent, pathological people — or at least their behaviour. It is very common for newspaper articles, talk show hosts, and people on the street to ask what the parents did or failed to do to make their kids into monsters.

Take two examples: In the novel (later a movie) We Need to Talk about Kevin, Lionel Shriver asks whether Eva, a mother telling the story in letters to her absent partner Franklin, is responsible for their murderous son Kevin. The novel is dense, ugly, and very readable, circling malevolently around what Shriver adeptly characterizes as “every parent’s latent fear that it was possible to do absolutely everything right and still turn on the news to a nightmare from which there is no waking.” Eva is an unreliable narrator, but every indication is that she was unloving, emotionally and physically abusive, a terrifying mother to a sociopathic killer; she thinks he was born that way, but Shriver gives her reader even odds that Eva made him into what he became.

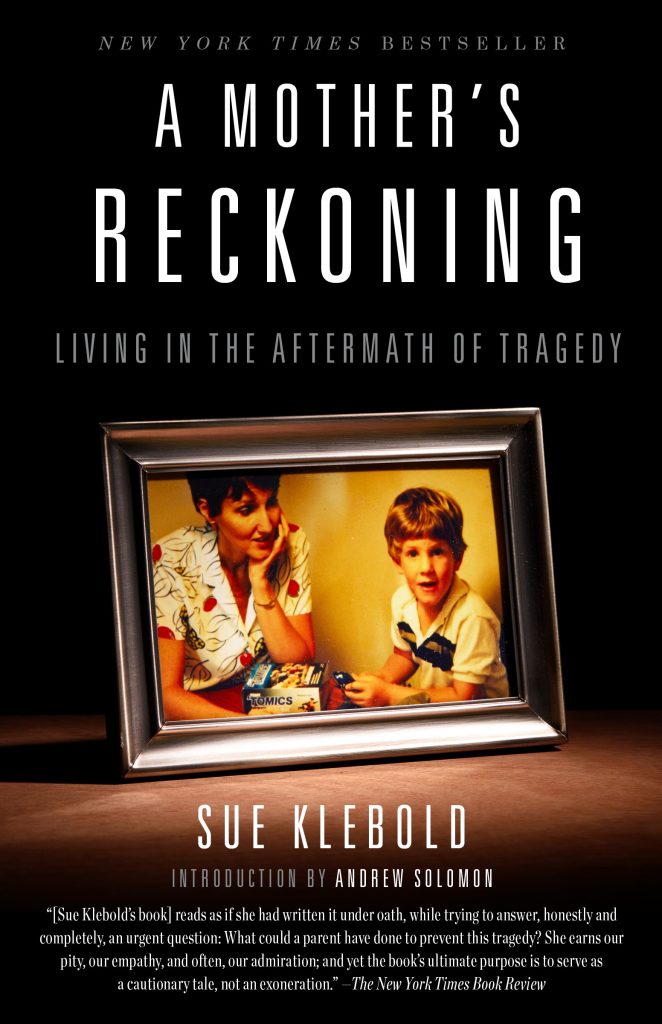

In contrast to Shiver’s incisive, pitiless writing, Sue Klebold’s memoir A Mother’s Reckoning: Living in the Aftermath of Tragedy offers an earnest engagement with actually, in the real world, trying to do absolutely everything right and turning on the news to find your child is one of the Columbine killers. The memoir takes up the question of whether Klebold and her family are responsible for Dylan Klebold’s actions, directly answering the many people who wondered how they could have missed the signs that he was preparing to commit mass murder and kill himself. Sue Klebold characterizes herself and her family as having done everything right, certainly not as unloving, abusive, or terrifying — but still as responsible for not recognizing that Dylan Klebold was in a mental health crisis. She writes, “We don’t lose our bearings because we’re bad people. Persistent thoughts of death and suicide are symptoms of pathology, not of flawed character” (xii).

Klebold is right to argue that turning toward parents in trying to explain school shootings implies a conception of character: Our character is shaped by the people who raised us. In that conception, withdrawn or abusive parents are partially responsible for kids becoming the sorts of people who kill others.

Shriver’s novel too enacts such a conception, along with a persistent theme that school shootings are a matter of imitation and one-upping other school shooters. Klebold turns toward medicalization, a disease model of murder and suicide, and affirms the view that how we report about school shootings contributes to the likelihood of copy-cat killings. Such a model is tactically effective, I believe, and epidemiological attention to clusters of suicides shows us that it does matter how imaginable self-harm is.

I honor Sue Klebold for reflecting deeply on her son’s actions and turning her life after his actions towards preventing suicide and supporting youth mental health. But I think we should be unsatisfied with both the parents-as-authors story (producing flawed or good character in their offspring, Shriver’s approach) and the pathology unnoticed-in-time story (Kelbold’s). Both encode a conception of the self as settled, subject to a final signification. Reading our past — whether parents, genetics, or circumstance — as though it explains who we are and what life we can lead is part of the pattern Barthes describes as attempting to discern a secret. Such an approach animates quite a lot of self-help literature, in which we’re invited to find an explanation for our life in something outside ourselves that now constitutes our selves — so, God, trauma, abuse, good or bad schooling, good or bad genes, and so on. This self-help through external reference approach is weirdly woven together with a dominant strain of neoliberal responsiblization manifest in endless self-improvement. This second approach flattens out our history and social context, and we are all supposed to be equally capable of maximum optimization though heroic acts of individual will. I’m interested instead in how we nourish our capacities of self and world making starting from the understanding that relational and historical circumstances are the terrain upon which we change ourselves or the world – but also recognizing that they are not an end point for the work we do.

The constant revision of our selves

I see Jo Walton offering just such an existential-aesthetic model of selfhood and transformation. By existential I mean that she gives an account of self-making as an ongoing project without recourse to predestination and in the face of death. This project is one for which we can take radical responsibility, though only in the context of recognizing the actual world in which we live and the histories we inherit. Paraphrasing Marx: We make history, but not in circumstances of our own choosing. As someone prone to despair about the circumstances in which we find ourselves implicated, many of which we are helpless to affect, the approach to history Walton offers has helped me think about death and art.

Or What You Will’s narrator reflects on death, his own and others. He says, “terrible things are happening, and some of them in our names. Do what you can. Every little bit helps. Speak up for the voiceless, protect the powerless, open up choices for the choiceless. …We’re all going to die. Finding ways to save other people is one form of immortality” (316). And saving others, in Walton’s work, includes making and preserving art.

Reflecting on when and how books have achieved some kind of ongoingness, the narrator says:

“The monks preserved the works of antiquity as a side effect, manu scripta, copying them by hand and passing them hand to hand, passing them with no knowledge that anyone would ever really want them. They didn’t know the Renaissance was coming, that eager hands would be waiting to take them up, to print them, with the forms for big letters in the upper cases and the small ones in the lower cases of printers’ chests. Nobody ever knows what’s coming. It’s easy to lose sight of that looking backwards, when it all has the air of inevitability, but the future lying before the people of the past was just as dark and impossible for them to picture as your future is to you” (113).

When we feel despair about the state of the world, when we feel implicated in the terrible things being done in our names, it is reasonable that the future feels impossible to picture. Walton’s approach here rejects the idea that the world we receive dictates the world we can make together. She enjoins us to make something and pass it forward even if we’re not sure there are hands waiting to receive it. The novel offers the idea that the best way to manifest aliveness is to practice our own art towards futures we cannot picture. Saving other people also means witnessing and responding to beauty, passing forward, hand-to-hand, something that outlasts us.

The book asks what it means to work with our whole being on creating goodness that we will not personally experience but that we offer to the future. Recognizing art, it encourages us to “admit that we are moved, that we care, that this is important” (46). Seeing beauty, Or What You Will suggests that we might respond “the only way anyone can, by gasping at the wonder of it and then making art of one’s own. You can’t answer it or equal it or rival it, but it makes you see you have to give it the best you can because nothing else is good enough” (172). The only thing we ever really have to offer is what we ourselves can make, in our specific context and with our own self.

Equally, while we make work ourselves, we also only do it in relation to a collective framework – we witness and are moved by others doing this, and we then offer ourselves to them. Rather than a model of individual geniuses working alone, the approach here is a bumptious collection of enthusiastic makers of our own work and appreciators of one another’s work, in time and across history.

Habit-forming demands for freedom

To me, this encouragement to give the present and future the “best you can” evokes Audre Lorde’s conception of the erotic. The erotic is a felt sense of knowledge, life-force, and fullness that Lorde argues might animate our life. She characterizes the erotic as sensual (in some of the usual ways we think of eros, sexual and sensual) but also as arising when we write a poem, build a bookcase, dance, share joy with others. It cannot, she says, be felt secondhand. Having experienced the erotic in this sense, recognizing its power, we cannot settle for less. Lorde says:

“It is never easy to demand the most from ourselves, from our lives, from our work. To encourage excellence is to go beyond the encouraged mediocrity of our society is to encourage excellence. But giving in to the fear of feeling and working to capacity is a luxury only the unintentional can afford, and the unintentional are those who do not wish to guide their own destinies” (54).

The recursive process through which we pursue “this internal requirement toward excellence,” as Lorde puts it, allows us to go beyond the encouraged mediocrity of our society — and thus to encourage excellence in ourselves and others. That sentence “To encourage excellence is to go beyond the encouraged mediocrity of our society is to encourage excellence” reads like a transcription error, but it is actually a spiral, and one I believe Lorde constructed that way on purpose. Every time we center the power of the erotic in our own self-making, we are also contributing to a collective context in which others might also pursue excellence in this way.

Lorde frames such work as anticapitalist, centering a good that is not about profit. She writes, “we need to examine the ways in which our world can be truly different. I am speaking here of the necessity of reassessing the quality of all aspects of our lives and of our work, and how we move toward and through them” (55). Lorde here articulates an approach toward building our own capacities that requires changing collective conditions; this is not a voluntarist, individualist approach. Manifesting the erotic requires making a world in which we all can live good lives. And we contribute to that making through the work we do.

Robin Kelley’s book Freedom Dreams likewise tunes itself to the question of how we reassess every aspect of our lives, how we collectively change the circumstances in which we make history. For him, this too is a question of art. Kelley quotes Paul Garon’s writing about the blues as a poetic form through which we fantasize. Garon says, “Fantasy alone enables us to envision the real possibilities of human existence, no longer tied securely to the historical effluvia passed off as everyday life; fantasy remains our most pre-emptive critical faculty, for it alone tells us what can be. Here lies the revolutionary nature of the blues: through its fidelity to fantasy and desire, the blues generate an irreducible and, so to speak, habit-forming demand for freedom and what Rimbaud called ‘true life’” (quoted in Kelley 164). Positing surrealism as a revolutionary practice, Kelley centers art as one way that we access what Lorde theorizes as the erotic.

Building a habit-forming demand for freedom sounds good. How do we build such a thing? How can we have fidelity to fantasy? Or, to go back to Walton, perceiving the horror of all that is being done, and in our names, how do we continue transcribing hope for a future with trust that there will be hands to pass that work on to? How can we refuse the circumscription of the soul collectively forced on us by capitalism? How can we re-author ourselves even when we have been subject to abuse and violence? How do we respond to beauty and, gasping at the wonder of it, turn to then making art of our own?

I have found myself turning to actual art making for inspiration here, including my own work as a potter. On this, I really like this book Art & Fear. David Bayles and Ted Orland observe, “Your reach as a viewer is vastly greater than your reach as a maker. The art you can experience may have originated a thousand miles away or a thousand years ago, but the art you can make is irrevocably bound to the times and places of your life” (52). We create, but not in circumstances of our own choosing. We create, but only from where and when we ourselves actually live.

Bayles and Orland argue:

“The hardest part of art making is living your life in such a way that your work gets done, over and over — and that means, among other things, finding a host of practices that are just plain useful. A piece of art is the surface expression of a life lived within productive patterns. Over time, the life of a productive artist becomes filled with useful conventions and practical methods, so that a string of finished pieces continues to appear to the surface” (62).

I love this idea. Living our lives in a shape that produces work as its byproduct, as a surface product of patterns that nourish making, might seem a long way off from Barthes, let alone from E.L. James writing fan fiction about Twilight. I find possibility in the space of holding fidelity to a habit-forming demand for freedom, a commitment to the erotic, and — gasping at the wonder of it — making art in response to this world.

What would it mean to live our life in such a way that the work gets done, over and over? In such an approach to making art, we are also making a life, choosing what to do with our one wild and precious human life such that we keep fidelity to making of ourselves something beyond what our original authors may have intended. And when we do this together, politically, we can build collective possibilities for everyone and everything to be able to transform in this way too. Life as fanfiction!

As philosopher Lewis Powell put it in conversation about a draft of this piece, taking such an approach implies that “the texts you read, and the text that you are, can be reinterpreted and imbued with alternate meanings and trajectories.” We can make something unpredicted by the scripts offered us; we can make alternate trajectories. But, as with fanfiction, in our life we need others to participate in the kind of shared making, and meaning-making, that living in this world necessarily involves. May we all become splendid people, going on from where we are to make new histories that resist the circumscription of our souls.

(Thanks to C. Thi Nguyen for really great editorial help, and to ambyr, carbonel, Lewis Powell, Anna Weinstein, Vivien Shotwell, Chris Dixon, and James Kimmet Rowe for, variously, advice and beta reading about this post.)

Alexis Shotwell’s work focuses on complexity, complicity, and collective transformation. A professor at Carleton University, on unceded Algonquin land, she is the co-investigator for the AIDS Activist History Project, and the author of Knowing Otherwise: Race, Gender, and Implicit Understanding and Against Purity: Living Ethically in Compromised Times.