What follows is a guest post by Antonia Peacocke.

Art critics get a really bad rap. The stereotype of a critic is a haughty, pedantic grump who loves passing judgment on art—without being able to do anything creative themselves. According to the stereotype, critics are assholes ready to destroy the dreams of hopeful artists and intimidate the rest of us into feeling dumb.

This stereotype couldn’t be further from the truth. Critics—or, at least, great critics—are really not assholes. They love art, and artists too, and they are not here to intimidate the rest of us. To see the potential of great art criticism, it helps to read a great art critic.

Peter Schjeldahl is one of those great critics. He writes mostly about painting and other visual art. He’s a staff writer for The New Yorker now, although he came up as a critic at The Village Voice. If you don’t know him already, I’m jealous: you have some great reading ahead of you. I recently bought and devoured his new book Hot, Cold, Heavy, Light, 100 Art Writings 1988-2018.

Schjeldahl’s genius is completely wrapped up in his easiness: it’s not tough to read what he writes. He doesn’t befuddle you with art-world jargon, but he doesn’t insult your intelligence, either.

In an interview at the 2011 New Yorker Festival, Steve Martin asked him, “How did you escape artspeak?” Schjeldahl replied, “By being utterly unqualified for it. I mean, I have a high school diploma and I dropped out of college in the early ’60s and I never took an art course.” His humility seems sincere but misplaced. If he’s unqualified to write the unintelligible garbage that academics (sometimes) put out, he’s much better qualified to write well. Every philosopher knows how difficult it is to produce writing this simple.

Schjeldahl’s stuff is easy to read—but it’s also great as criticism, not just as fun breakfast-table reading. There’s one main reason why. He shows you how to appreciate art, by demonstrating how to do it yourself.

Before I say more, here’s an example of his doing this in a discussion of Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie Woogie:

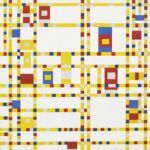

Look hard. That’s how to love Mondrian. … Maybe start … with Broadway Boogie Woogie. You have seen this jigsaw of colored lines and little squares many times. It is always up at MoMA. Now look hard. It is three pictures in one, each starring a color: red, yellow, blue. When you think red, the other hues defer. They do a jiggling routine in praise of the hero, red. When you think blue, blue steps out, and red joins the chorus. Then yellow, the same. (A fourth color, gray, shyly holds to a supporting role.) It really is like boogie-woogie piano, ping-ponging between left and right hands. (Hot, Cold, Heavy, Light pp. 256-7) [ed. note: links added]

What’s fabulous about this paragraph is how concrete and explicit the directions are. These are moves you can follow: back-of-the-box instructions for anyone. He’s getting as close as he can—in the medium of writing—to actually holding your hand, positioning you in front of the painting, and directing your gaze.

More important than physical positioning, though, is the direction of attention in art. Often we find art confusing or frustrating because we don’t even know what to attend to, or how to attend. The sophisticated attention-trick that Schjeldahl elegantly describes is to take in all the marks of one color at once, backgrounding the rest. That’s not something I would think to do before he recommended it. But once I did it, I understood better what there was to love in Mondrian—who had, I admit, left me cold for a long time.

Schjeldahl is ready with a kind, forgiving story about this common blindness:

It’s a dumb tack to take with most painting: to stare, to pitch into with your gaze, to burn holes in like a rube or a humorless child. Normal painting involves learned conventions. Not Mondrian. I promise you stabs of delight if you can gawk stupidly enough… (Hot, Cold, Heavy, Light p. 256)

As I sat around talking about these Schjeldahl essays with some other down-to-earth philosophers who write about aesthetics, we noticed something about him. He manages to demonstrate a method of looking without telling you what to see in the end. With Agnes Martin’s The Islands I-XII, for example, he writes, “it helps to shade your eyes. This causes tones to darken and textures to register more strongly” (p. 305). Or take another example: the better examples of Picasso’s Glass of Absinthe sculptures “function in the round,” he points out. “Circle them. Each shift in viewpoint discovers a distinct formal configuration and image” (p. 191).

Although Schjeldahl sometimes leaves out the upshot of his looking, he’s not hiding what he really thinks. Picasso is an “amateur—nearly a hobbyist—in sculpture,” and his Head of a Woman “fails” as a “painter’s folly;” Francis Bacon is, on the whole, overrated. A show of works by Willem de Kooning left him “beaten to a pulp of joy,” and Francisco de Zurbarán’s Still Life with Lemons, Oranges and a Rose is a “tour de force.” Final evaluations still have a place in this criticism, but they are not its primary purpose. The primary purpose is to welcome you into art, even if you’re not already into it, and keep you there.

Unlike other critics, Schjeldahl rarely takes pleasure in negative reviews. They’re often short, and sometimes funny, but you don’t get that puerile Burn-Book glee from reading his grumpy stuff. Usually you just feel (with him) a quiet and genuine disappointment that there could have been something there to love, but there wasn’t.

This critic makes a lot out of being unlike other critics. In 1981 he wrote:

many journalistic art critics today are testy, defensive, and carping… The average piece of bad criticism a decade ago cozied up to some rising artist or art idea and implied that anyone who couldn’t see the critic’s jargon as a form of higher common sense was an idiot. The average piece of bad criticism today reads like something from Consumer Reports. The art is tested; its tires are kicked. Pretensions to importance are attributed, inspected, and dismissed. The critic glories in remaining unmoved: “Ha ha, you missed me!” More artists hate — really hate — more critics today than ever before.

These remarks, republished by The Village Voice in February, still resonate today—that is, if you substitute in Rotten Tomatoes for Consumer Reports (does anyone but my parents pay that subscription fee any more?).

The model Schjeldahl offers instead is laid out in a manifesto (a “Credo”) that closes Hot, Cold, Heavy, Light. Here he identifies with Oscar Wilde’s model of active, autobiographical, emotional engagement with art in criticism.

Ironically, this last piece is the least compelling in the book. For an essay about “self-consciousness as a workaday tool,” it oddly lacks self-awareness. He gestures at a few general thoughts about criticism—the critic’s first-person report is an idealization of confidence; the unmoved critic is boring; two critics who agree are redundant—without properly characterizing what is so refreshing and wonderful about his own work.

Here’s what I got from this essay: there’s criticism, and then there’s philosophy of criticism. Philosophy is for the critic as ornithology is for the birds, we might say. (Sorry, sorry, I know.) Seeing what Schjeldahl is doing requires philosophical analysis. That’s not his forte—and why should it be? He’s an art critic. But even if he can’t express in abstract, general terms what is great about his own criticism, his methods express commitment to a certain model of criticism anyway. I’ll try and characterize this model, in my own mode as philosopher and not critic.

Schjeldahl’s methods use a demonstrative mode of criticism, one which takes the work of the critic to be just like the role of the aerobics teacher at the front of the class: show the rest of us how to do it. What is “it,” here? Appreciating art. What he shows us how to do is, more specifically, all sorts of things that allow us to fully appreciate art: attend like this; move around like that; try interpretations on for size, crazy as they may be; argue with yourself; physically come back for more, because you’ll forget what things look like without even knowing it. The measure of your (and the art’s own) success will be the love you find for a work. It won’t always be the same—love can be hot, cold, heavy, light—but you will feel it if it’s there.

Implicit in this demonstrative method of criticism is the insistence that you have to do it yourself. What’s “it,” again? Appreciating art—face to face. Making the connection with the Acquaintance Principle—given by Richard Wollheim in his influential 1980 book Art and Its Objects—is absolutely irresistible. The principle runs like this:

judgements of aesthetic value, unlike judgements of moral knowledge, must be based on first-hand experience of their objects and are not, except within very narrow limits, transmissible from one person to another (p. 233).

Here’s how it seems to me: Schjeldahl would be disappointed if you just took his word for it that de Kooning merits rapture, and Velázquez sheer wonderment. This critic invites, and occasionally demands, much more engagement with art, not less. He wants you to go and see for yourself, even (especially) after reading what he says. But that doesn’t mean you’ll be by yourself when you do go, if you’ve managed to turn Schjeldahl into a voice in your head. He writes, in his piece on Zurbarán, that

It helps when the specter of a particular person, who particularly loved particular things, stands at your shoulder, urging attention, inviting argument, and marveling at the shared good luck of being so entertained (p. 28).

It’s not surprising that this critic also used to be a professional poet. Schjeldahl published several volumes of poetry before quitting in the 1980s to become an art critic. There’s a piece in Hot, Cold, Heavy, Light that should certainly count as prose poetry. Here’s a sample of this ode to concrete, the building material and sometime art medium:

Concrete is the most careless, promiscuous stuff until it is committed, when it becomes fanatical. … Promiscuous, doing what anyone wants if the person is strong enough to control it, concrete is a slut, a gigolo, of materials … Only give it a place to lie down, of any shape, and it will oblige. But let concrete set, and note the difference. … Once it has set, concrete becomes adamant, a Puritan, rock, Robespierre.

So let me take on the critic’s mantle for a moment and leave you with these words about Schjeldahl, practically plagiarized from the master himself:

Go read him. And read him with joy. It’s a dumb tack to take with most critics: to browse for fun, to drip milk from your breakfast cereal onto the pages of the book propped up with your coffee. Most criticism involves learned conventions. Not Schjeldahl. I promise you stabs of delight if you can giggle artlessly at his turns of phrase, and wonder with him in his love.

Notes on the Contributor

Antonia Peacocke is an Assistant Professor of Philosophy at Stanford University. She loves visual art and she also writes short fiction.

September 24, 2019 at 10:25 pm

This is a great article and I am happy to see AFB discussing details about what a good art critic actually does. Nice illustrations here of his writing. But for me, no art critic will ever top Arthur Danto (writing as real art critic, not philosophical art critic)–as when he talked about not wanting to critique some of Julian Schnabel’s paintings because they were like shaggy dogs wagging their tails very hard in trying to be liked. I always read Schjeldahl religiously but I can’t agree about his writing being always simple and easy to read. Maybe, yes, he eschews art jargon, but he’s often quite precious in frustrating ways. I took him on in a publication of mine, “Against Raunchy Women’s Art,” and discussed his review of Lisa Yuskavage’s art (here I take the liberty of quoting myself):

Consider some of the self-contradictory criticism Yuskavage’s work evokes. Peter Schjeldahl writes about Yuskavage’s women that, “They seem nice sorts who have sexuality as others have the Ebola virus.” The implication is that these women’s sexuality is like a fatal illness that has befallen them, something regrettable that can be lethal both to themselves and to others. Schjeldahl tries to complicate things by remarking, “They would be pathetic if we could pity them or contemptible if we could scorn them. As it is, the paintings rule out such comfortable responses. To behold Yuskavage’s creatures is to dive into an existential soup with them” (Schjeldahl). What is this “existential soup”? It has to do with “the wild wisdom that we must, finally and again, deal seriously with the bottomless givens of our nature.” If this is true, it is horrifying: but I doubt that the “bottomless givens of our nature” truly include an attraction to women with anatomically impossible sexual parts. In fact, Yuskavage’s paintings reduce Schjeldahl, an unusually articulate critic, to nonsensical babble as he writes, “The intelligent way to look at this art is dumbly.” No thank you; I have no desire to be dumbed down by stupid art.

Schjeldahl, Peter. “Girly Grotesquerie: Lisa Yuskavage at Marianne Boesky Gallery in New York.” Artnet.com. 9/25/98. Retrieved 20 July 2009.

September 26, 2019 at 9:41 pm

As a philosopher who writes art criticism, I’m also glad to read a good philosophical discussion of what critics do. Schjeldahl is an exemplary belle-lettrist, along with other poet-critics like Frank O’Hara and Bill Berkson. As such, questions of writing (voice, mood, tone) tend to be front and center in weighing his work. The demonstrative method, modeling with gentle imperatives how a viewer might allow her attention to unfurl across a work, is particularly well suited to his style. He rarely makes systematic claims, but his essay on surrealism is one of the sharpest attempts to make sense of what’s still the 20th century’s most enigmatic movement. On the downside, I also fully endorse Cynthia Freeland’s critique above–the peril of belletrism is producing overwritten prose that strangles thought.

My own interest in criticism–why I started practicing it, and why I find it an activity worth thinking seriously about–also has to do with these questions of writing. Despite the torrents of prose that philosophers produce, there’s depressingly little discussion of why we might write in one way rather than another, and whether the ways that we do write are really best suited to what we are trying to accomplish. Criticism invites, if not requires, a form of writing that feels truer to the experience of encountering art. Encounters are potentially boundless, and they tend to render theoretical rules for interpretation and judgment beside the point. None of them offer much support when you are actually standing in front of a luminous Jeff Wall photograph or entombed within the anechoic steel curves of a monumental Richard Serra sculpture. Theory hovers high in the thin air, rarely descending to participate in these mundane encounters. Any thread that leads you out of the dark terrain of unknowing has to be one laid down yourself.

The struggle here is the search for a particular kind of apt description: finding words that adhere to the work, that convey its texture and weight, that evoke the ripples of perception and feeling that it produces, and that let its meanings, in the widest possible sense, shine through. Expression, description, interpretation, and judgment become seamless and inseparable in ways that academic philosophical writing downplays or outright disallows. Importantly, this form of critical writing can itself constitute a form of argument, though one that produces conviction only because it edges right up against the nondiscursive.

In building on Antonia’s excellent contribution, it would be useful to open things up to broader ways of producing “great criticism” besides the belletristic imperative mode. Luckily, the critical landscape these days is a rich one. Newspaper and magazine critics are a vanishing breed, but include Roberta Smith, Barry Schwabsky, Nancy Princenthal, and Carolina Miranda. There are other “writerly” critics like Dave Hickey, John Berger, and Peter Plagens, each of whom place attitude and sensibility at the center of their practice. There are the academic critics, notably Rosalind Krauss, David Carrier, Benjamin Buchloh, and Arthur Danto. Here, not surprisingly, generalizing, synthesizing, and reflexivity tend to be prized. (Although making sense of how Danto’s critical practice coheres with his official views about art is not at all easy!) There are critics who excel at placing works within their social/political context and discerning movements and currents in the artworld and wider culture: e.g., Lucy Lippard, Mira Schor, Ben Davis, Orit Gat, Hito Steyerl, and Paddy Johnson. (Or, for that matter, Kenny Schachter’s Instagram feed.) And there are writers whose works spin outward beyond even the capacious boundaries of criticism into the wider space of “artwriting”. Here, I’d single out Lynne Tillman’s “Madame Realism” and Rebekah Rutkoff’s “The Irresponsible Magician”, both of which reveal acutely how conventional and unambitious much criticism is.

All of the writers mentioned above practice criticism in highly varied but equally ambitious ways. What counts as quality in one mode may not be foremost in another. I’d love to see the philosophy of criticism set as its goal to be as capacious as critical practice itself.

September 27, 2019 at 10:15 pm

On the topic of Danto as philosopher/critic of art, two links: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Danto-and-Art-Criticism-Freeland/bd89d8948c0494f758d6b10788387377e69bc7af

https://quod.lib.umich.edu/c/ca/7523862.0006.021/–danto-and-art-criticism?rgn=main;view=fulltext