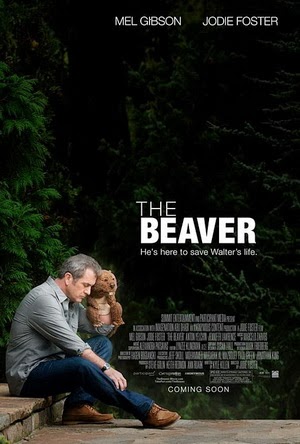

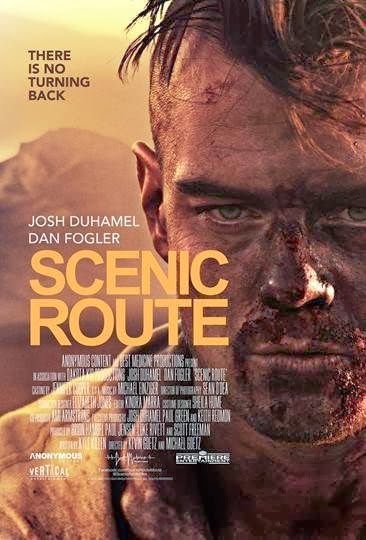

What follows is an interview with Kyle Killen. Kyle is a film & television writer and producer. He is the creator and showrunner for the critically acclaimed Fox television series Lone Star, Awake (NBC), and Mind Games (ABC premiere Feb. 24th). He also wrote the screenplays both for the films The Beaver (2011), starring Mel Gibson and directed by Jodie Foster, and Scenic Route (2013), starring Josh Duhamel and Dan Fogler and directed by Kevin and Michael Goetz.

Though unfairly cut short after only a season, your television series Awake managed to attract quite a serious following. These invariably include an element of obsessive fandom for which engagement with the work often consists of meticulously pouring over each part and subjecting it to analysis at an almost frightening level of detail, and extensively cataloging any and all inconsistencies, incongruities, loose threads, and holes uncovered. Such folks are often referred to as nitpickers. I think that label to be a touch unfair as nitpicking implies calling attention not just to some small mistake or minor flaw of a work but to those very mistakes or flaws to which audiences needn’t attend or should outright ignore in the first place (e.g., tips of boom mikes visible in the top of the shot, jet contrails faintly visible in the Middle Earth sky, etc.). That is, to label someone a nitpicker is to claim the relevant flaw lies with them and not the work. Where do you tend to draw the line between legitimate criticism and obsessive nitpicking when concerning your own work, especially Awake, which has a quite complex and detail-oriented structure?

I have no issue with nitpickers. Any and all issues are up for debate as far as I’m concerned, and while sometimes criticisms point out things we chose to ignore, they also occasionally point out things we simply missed. Awake was a beast to keep track of, and then in the process or editing down to the 42 minutes you have available for actual story content in an hour of television we necessarily excised things that might have made particular aspects of the story clearer or more logical. One would hope that with more time we’d have gotten better about judging what would fit from the start and avoided leaving important bits on the cutting room floor. Regardless, when one notices something that bothers or takes them out of the flow of the story I can’t really say that they should simply ignore it or that it’s somehow not legitimate.

When major motion pictures such as Ridley Scott’s Prometheus and Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight Rises are ridiculed for their glaring plot holes, inconsistencies, and wholesale violations of commonsense, with whom do you think the preponderance of blame most likely to rest (e.g., the director, producers, writers, actors, or audiences themselves)?

Plot holes usually come down to one of two things – either the issue is not considered important enough to the story or the thrust of the story to bear addressing, or it was addressed at some point but had to be cut out for some reason (time, cost, etc). The larger issue I think is why it sometimes matters and sometimes doesn’t. Once you’ve spotted a glaring inconsistency such that you can’t engage with the work anymore, it becomes hard to fathom how someone else could either miss that issue, or see it and not have a similar reaction. But the fact that a number of the titles you reference as being ridiculed for these inconsistencies or plot holes were actually spectacular box office successes indicates that while these issues greatly bothered some, they did nothing to deter the audience at large. Blame seems like a strong word, but essentially, feature films are designed to provide entertainment to turn a profit, so it’s unlikely those putting their financial resources at risk would do so if the audience had demonstrated that bulletproof logic was something they factored into their viewing decisions. When something bothers an audience, it tends to go away – for example the failures of a number of films set around the Iraq war made it difficult to find money to make more of those projects. The returns on summer features indicates that plot holes and faulty logic have approximately zero impact on the audience at large and their enjoyment of blockbuster films. Which is not to say an illogical film can’t flop (see: Battleship) but merely to say that logic tends not to be the deciding factor.

Compared to that of most other art forms, film production is a messy enterprise involving scores of people all playing distinct but interrelated roles. How do you see the role of the screenwriter in film production as compared to other roles (producer, director, cinematographer, actor, editor)?

The screenwriter is like an Architect. They draw up blueprints such that a number of other people decide this is something worth building. That’s kind of it. Once the building process begins, things change, the ideas, good and bad, of the countless number of people required to turn paper into film all get baked in and what results is really the organic creation of everyone involved. John August (a prominent and successful screenwriter) has suggested changing the Oscar category for screenwriting to ‘Best Movie based on a screenplay’ which really reflects how things necessarily change and grow once the script heads for screen. Compared to other roles, the screenwriter has the initial say in what something ‘could’ be. They have the opportunity to make the first argument for something’s need to exist. After that it becomes what it becomes through the efforts, successes, and failures of those who make it real.

How do you think the relationship between the script and film compares to other broadly similar relationships such as plays to theatrical performances, scores to musical performances, architectural blueprints to physical structures?

I think screenplay to feature film likely has the loosest relationship of those you cite. In theater the text is sacred and you require the permission of the writer to alter it. The stage is necessarily a suggestion of a world, and the words and actions described in the play are the only things available to bring it to life. Builders also see largely their job as to faith execute architectural blueprints and deviations tend to happen because of specific circumstances or unforseen issues as opposed to as a result of creative choices. Scores tend to dictate as much as possible to musician in an effort to insure that what happens in reality mirrors what played in the composers head. Screenplays in feature film tend to be much more of a first step. When you introduce the camera, the director has tremendous power to influence what you see and experience, what you note as important, and what you disregard. Think of your favorite book that resulted in a movie and consider how different the two are, even if you happen to like both, and you get a sense how the film evolves from the stage where it’s a story to the place where it’s a movie. Even the most faithful adherence to words on a page doesn’t begin to account for the mood, tone, pace, and style of a film. Look at something like The Social Network, which is a distinctly Aaron Sorkin screenplay that was largely adhered to, but it’s a strikingly David Fincher film, and had you read it before Fincher made it it’s unlikely it would have played in your head the way it ultimately did on screen.

Since it’s release in September 2012, the number of times Leos Carax’s Holy Motors has been screened anywhere in the United States works out to roughly half the number of times Paranormal Activity: The Marked Ones was screened within a 25 mile radius of my home in a single day [Jan. 9th, 2014]. Do you think mainstream contemporary American cinema & television affords its audience the respect it deserves? Do you think audience respect any different for mainstream contemporary American music or literature? Or might the Domestic Box Office Gross, Nielsen Ratings, Billboard Charts, and NYT Bestsellers List reflect a case of just desserts?

I think films are extremely expensive to make, and the more you bet the safer you want that bet to be. That doesn’t mean making giant tentpole films is a ‘safe bet’ (see again: Battleship) but it does mean that audiences, over time, have shown a strong preference for things in the vein of Blockbusters over films like Holy Motors. Rather than offer a value judgment, I’d propose an explanation. For most of us films are a diversion, a small and occasional part of our lives during which we hope to be thrilled and entertained. For people who are immersed in film or television, or books, the similarity of many the products on offer becomes tiresome and there’s a thrill and an excitement in seeing the form riffed on and reinvented in something like Holy Motors. But if you haven’t ingested such a volume of material, if you see two movies a year and one of them is a Transformers film, you may not be feeling a sense that someone needs to break the mold. The mold may still be fresh for you. And as such, things that offer a ‘reaction’ to mainstream cinema, books, or television, might seem unnecessary or uninteresting. This is where the world of television has become exciting because the fracturing of the audience has made the pursuit of niches the model for establishing your network and sustaining your existence. The big tent broadcast model is withering while the carving up of the audience into small but reliable populations who enjoy similar things is flourishing. It’s unlikely this will ever result in a something like Holy Motors being on 3500 screen across the country or selling out on Friday nights. But it does mean that there’s a way to reach out to and connect with people who enjoy those types of entertainments and a way to make them decent financial gambles rather than art for art’s sake.

The rise of digital media has already shown itself to have devastating consequences for industries unprepared or unwilling to adapt (e.g., the recording and publishing industries). To what extent, if any, do you think the move from celluloid to digital will shift film-making away from the current major studio model to something perhaps more egalitarian? Do you think the studio system will remain viable in the next few decades? In not, what do you see or hope to see as taking its place?

I think the rise of digital production and distribution as well as the technological revolutions surrounding the raw equipment needed to make films certainly opens the door to a much much larger number of people. I think it allows for much more production outside of a studio environment and allows lots of alternative way to reach your audience. But I don’t think it tears down the walls of the existing system. Studios are aggregators of talent and marketing machines. You can lower the barrier to entry, but the world in which you wish to release your film is noisier than ever. Marketing budgets have exploded as the cost of equipment has shrunk and ultimately it doesn’t matter if you can make a film on a 1500 dollar camera if you can’t afford to tell the world it exists. Word of mouth, festival lightning in a bottle, etc., are certainly ways that little movies can break through, but blunt force awareness raising and salesmanship is a business studios are likely to be in for a long time. Where I think digital demands an immediate rethink is in distribution. The head in the sand, sue our customers approach of the moment is utterly doomed. When one can obtain a copy of a film for free, instantly, and not have it be crippled by various DRM or unskippable warnings and previews, when the experience of STEALING a film results in a BETTER viewing experience for the end user then you have a serious problem that cannot be addressed by merely shaming your audience into doing things your way. Until paying for content offers an experience as frictionless as stealing it, stealing will remain appealing to otherwise upstanding citizens.

Similarly, given the rapid and radical shift in content delivery, the Nielsen system looks to be hopelessly antiquated and woefully inadequate method of reliably gauging popularity of television shows. What do you see, if anything, as taking its place? Do you see network television as a result willing to take more artistic risks (e.g., NBC’s Hannibal is arguably the most aesthetically sophisticated show on television)?

Measuring audiences and understanding their viewing habits has become increasingly tricky and while I wholeheartedly agree that the metrics we once relied on are becoming increasingly meaningless, I’m not sure we know what the next answer is. Twitter and other social networks seem to have tapped a digital well of information about what we’re actually watching, but it’s noisier and self selecting data. I think before we can really figure out how to count people we have to figure out what watching a show even means anymore. The broadcast model is based on the idea that you’re selling an advertising delivery mechanism and if technology means people aren’t watching the ads, then they’re not watching the ads. Pretending it’s otherwise is simply whistling in the dark. Netflix and premium cable outlets like HBO demonstrate that end users will pay directly for programming which leaves advertisers out of it, and I think you’ll see variations on that model expand. Ironically, things like twitter are simultaneously becoming the new way to count viewers, while being one of the only new technologies to drive people to watch television in a more TRADITIONAL manner. When a show like Breaking Bad achieves cultural ubiquity such that one cannot hide from news and reactions to every episode, the idea of storing it on the DVR for five days becomes less appealing. Social discussion creates a need to watch things as soon as they’re released in order to be in on the conversation. The question is, does anyone think the people eager to tweet about a show the minute it’s over aren’t savvy enough to start it twenty minutes late and skip the commercials?

As for taking more risks, yes and no. Yes, when you have little to lose, as NBC did in the case of Hannibal, you’ll take some swings. And as networks become more narrowly defined and their audiences more specific they can certainly afford to try things that might not have the traditionally required big tent element. But the larger issue is the sustainability of any of todays broadcast and cable models. Always on, on demand content delivery is where we’re going and Netflix demonstrates that it’s lunacy to pretend you need to pay 50 dollars a month for a basic cable TV package to then have the right to subscribe to your favorite HBO shows. But as more distribution drifts toward the ala cart, direct to consumer model, outlets that don’t have shows that appeal to consumers now will wither and die. And many of the successes of the recent decades have come from outlets like AMC that existed and were already being paid for by consumers before they decided to develop content that would appeal to larger audiences. Whether that somewhat socialist bubble of basic cable was actually key to the providing the opportunity that AMC eventually availed themselves of is up for debate. I don’t know what TV will look like after the current structure breaks down. But I do think we’re going to find out.

February 7, 2014 at 2:17 pm

Good stuff, Christy and Kyle. I had a question for Kyle. You mentioned above that the relationship between what is written and what is produces is loosest in feature film making. I was wondering first if television is more of a writer's medium and second, given the tighter coupling between the word and the stage play (for example) if that's something that appeals to you as a writer. Do you have any inclination to write for the stage (or have you done so already and I just missed it)?

February 11, 2014 at 2:09 am

Television is absolutely a writer's medium. Breaking Bad is Vince Gilligan. His vision is the one things that persists episode to episode, season to season. It's akin to being a writer/director in features, which is the other way to bring the relationship between script and screen closer, and the one that appeals most to me.