Chalk board drawing, series Film Stills, “Appropriation” (2016)

Artist Jörg Reckhenrich interviewed by Alex King

Jörg is a Berlin-based artist. With an understanding of art – shaping the social space – he takes the creative principles to the world of organizations. Art, he believes, can open our eyes to understand that we are not moving forward to a goal, we are at the goal and changed with it.

An important theme that runs through your work is the power, energy, and vitality of words (something we philosophers love!). Even in your performance pieces like Dialog Skulptur (Dialogue Sculpture), the spoken word and the dialogue format become very important. Why do you think it’s worth thinking more about words or experiencing them in a different way?

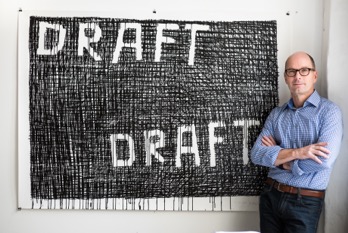

Words really have an energy for me. Many years ago, I spent time with mantra techniques, repeating words over and over again. And I found that if you repeat words, they unfold. Each one has a certain quality, a rhythm. This is something that people have known for thousands of years, and they use it not only to express something in a more contemplative way, but to bring out the energy of single words. If I write down the word ‘draft’ [ed. he showed me such a draft in his studio, see below], it’s not merely the simple meaning that comes to my mind. It opens up whole new worlds. Behind the actual meaning, there is the sound of the word. But also, what is a draft? A draft could be something written, roughly written on a paper, it could be offering a situation, a rough sketch, whatever it is. Words are the doorkeepers for a broad variety of images and associations. So you can take a text in two different ways. One is just to read through and, hopefully, understand the meaning. The other is to experience the field that these words create. They create a field that’s somehow beyond the single meaning of the words and the sentences. A good story presents a full picture of a situation and helps you to think about the new world it opens up for you. So because they open up these fields of images and associations, words have a very energetic aspect.

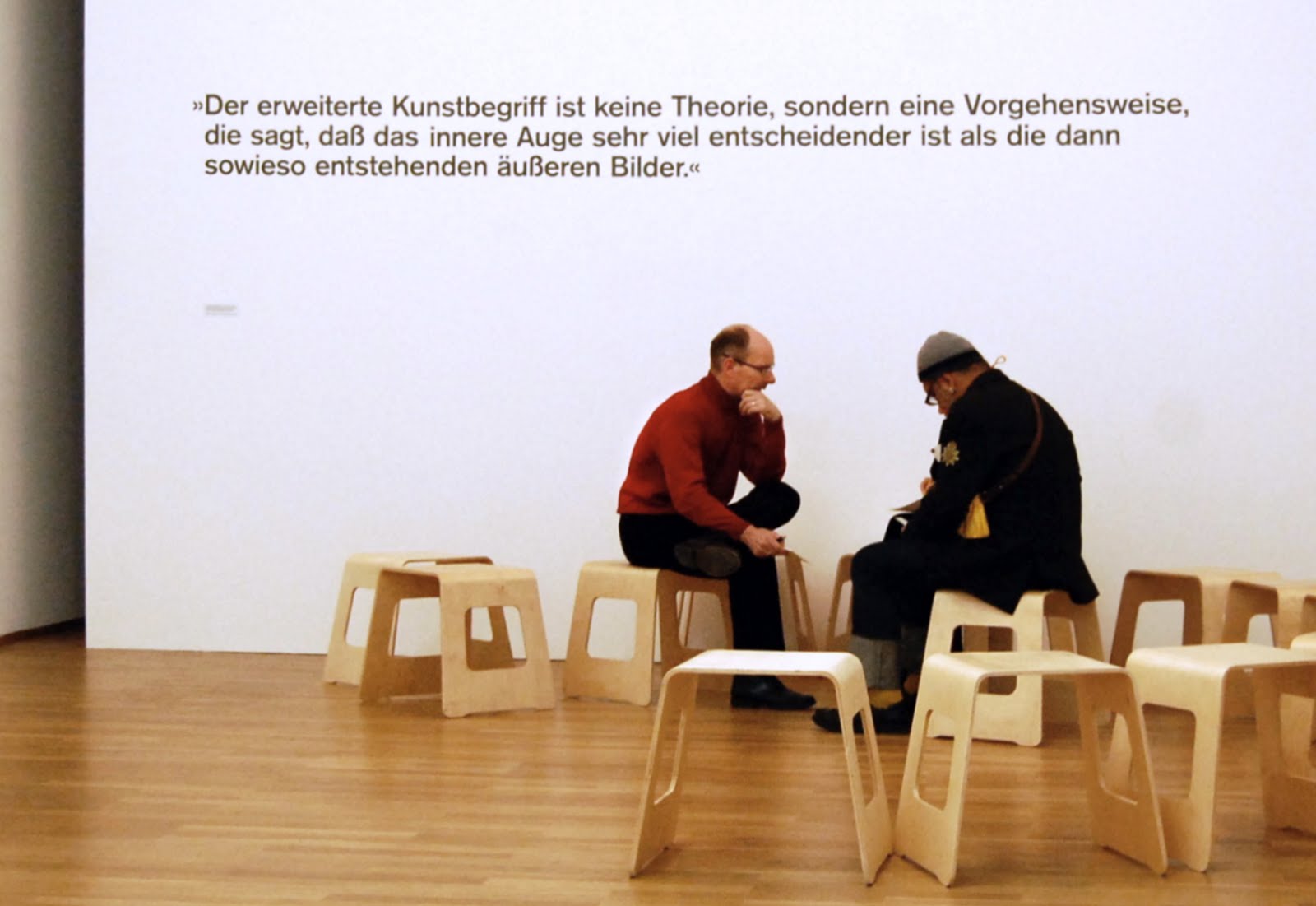

The “Dialogue Sculpture Project” (2008)

(translation: “The broader concept of art is not a theory, but an approach that says that the inner eye is much more significant than the external images.” -Joseph Beuys)

You’re a native German speaker, so why do you so often use English rather than German? Is it just because English is more accessible?

No, it’s not about being more accessible. Historically, first of all, I started to teach in English, so it became second nature for me when speaking with people and doing programs, keynote lectures, and so on. English is my performance language. It’s the same phenomenon as we saw in Germany in the 70’s. People started to wonder whether to produce music pieces in German or in English. Using simple German words is too direct for me. I have in mind exactly what is meant. English has more of a distance, so it’s more abstract. I can use the distance proactively. If I used German words more, I’d have to dig deeper for a more abstract expression or an abstract version. That makes it easy for me in English, or simply said from an artistic point of view, productively helpful.

Studio Situation, “Inflammables” (2011)

For your very interesting Invisible Sculptures projects, you have people sit and focus at length on a single artwork and then form a kind of group interpretation through discussion. Do you see this as collective, interactive performance art? Or is it not itself art, but instead a purely didactic exercise for helping people learn how to approach art?

The idea of Invisible Sculptures is probably the core of my work. To be honest, opening that space and letting something emerge out of that dialogue, in a good situation, really is a performance. When I do these programs, I know that most people treat it like more a didactic exercise about how we share thoughts, and that’s it. But when you open up that situation again and again, and you play around with the different ideas people have, then you can see you’re triggering a situation where a space can emerge. And you feel this; you sense this. “Ideas are material,” says Beuys. I really believe that. All I have to do is facilitate this situation. And it’s a simple process, so all you do is ask questions. If you look at a piece, probably after twenty minutes you’ve seen it all. But if you really keep it going by probing with questions over and over, there’s still something, even if you think you’ve seen it all. If you dive through this, you come to what I call the turning point. If you keep on going, I promise you, something will emerge. Something that is different, something that was not there before. For some, it’s an introspection, a new perspective of the artwork. Something new seeps in from a completely different point of view, and not from the cognitive brain. It becomes a very personal experience. This is the most important point. And it’s not about the artwork. It’s about sensing the space we have all created. So in that sense it’s really a performance for me or performance art. And I really love to do this. This is probably the most beautiful thing you can do with other people.

Obviously there’s something nice about getting a group together to discuss different interpretive insights, but do you think there’s anything that comes out of the group interpretation that couldn’t come from an individual’s interpretation? Or is it just more likely that you’ll get a greater variety of ideas from a variety of individuals?

Definitely yes, you really get something different. I can tell you a simple story to illustrate this. Many years ago, I was with a group looking at a Cy Twombly piece. After about ten minutes, one woman said, “I can’t stand it, it makes me nervous.” And I was surprised – I thought it was just a poetic piece, to take simply. But I moved away with the whole group and asked her, “Is it better now?” And she said, “Yes, of course. Now I have a better overview.” So we went on with the discussion, observation, and dialogue, and after about an hour and half I asked the group, “Can we move back closer to the painting again?” She said yes, but I sensed the tension. So we moved right in front of the piece. One woman was saying, “Oh, what an amazing situation, that fits my life perfectly. I can move from space or plot from point to point and nothing determines me!” And the other woman answered, “But you need an aim in your life!” I thought that was incredible. So, because people bring in such different observations, simply comparing and building out from them creates something different from one person sitting in front of a painting and making an interpretation.

Inflammables No. 1, “Make the Secrets Productive” (2012)

Sometimes it seems like interpreting art is a bit like interpreting a Rorschach blot: It reveals much more about what the interpreter brings to the table than it does about the blot. Do you think that this is an apt or inapt comparison?

I think it’s really both. I mean of course there is a story which is told. If you look to a Rembrandt, even a Cy Twombly, or a Barnett Newman, there is an idea behind it. And we would really miss the art if we said it was just about our interpretations and how we digest the piece. We’d miss something if we talked in front of a Cy Twombly not about the poetic aspect, not about a scriptural way of communicating aesthetic information. These pieces are not made by accident. There’s a selection of technique, of picture, of structure, etc. We’re looking at something which was actually created. But artists tend not to say things like, “Well, I’ve thought about a scriptural attitude and therefore I invented the technique I’m using.” You never hear Cy Twombly speaking about that idea, but it’s there. The Cy Twombly story from the previous question is relevant, too. The interpretation reveals a lot about the interpreter’s situation. Sometimes, in this process, I have them write down their initial observations first, before we speak. Daniel Kahneman talks about how we influence each other with the information we present. With interpretation, maybe I see colors, but you see structure, and so I learn from you. But if you think about me as an artist with a lot of experience, I influence what you think. It’s the same if you talk about philosophy. I’d back up because you’re the expert. I would listen to you instead of bringing my observations out and putting them on the table. So having people write things down helps mitigate that.

Do you see a need in interpretation for authorial intent and contextual factors surrounding the work? For example, you’ve been very influenced by Beuys, and you are yourself German, working in a reunified, post-Cold War country in a time of intense globalization. Is it important to understanding your work – or art in general – that people recognize factors like these?

Simply said, no. If you look at the current situation for artists, all this kind of information is available. But I don’t think it’s important. The contextual information is more for myself. I’m very aware of the time and situation when I was born, of Beuys as an influence, etc. But I raise a simple question: How can we unleash our creative potential? What kind of a difference can we make? Looking at it from outside, those contextual things about me aren’t important to those questions at all. For example, three years ago, there was a fantastic Rothko exhibition in Hamburg with lots and lots of paintings. They presented the paintings as purely aesthetic pieces, without a lot of context. So we had to admire and contemplate the pieces themselves. But then a friend of mine told me that the CIA had put tons of money into abstract expressionism because the artists made a counter-statement to the stuff that came over from the Soviets. They wanted to create a countercultural statement: we are different, we have this open, free-spirit… The context is information and of course important. But what I try to do is to give the person who is looking at the artwork the freedom to observe and to make their own judgment and find their own meaning contemplating and thinking about the piece first. As part of the process, we bring in the context, but only later. How to balance their own experience and the context is important to me.

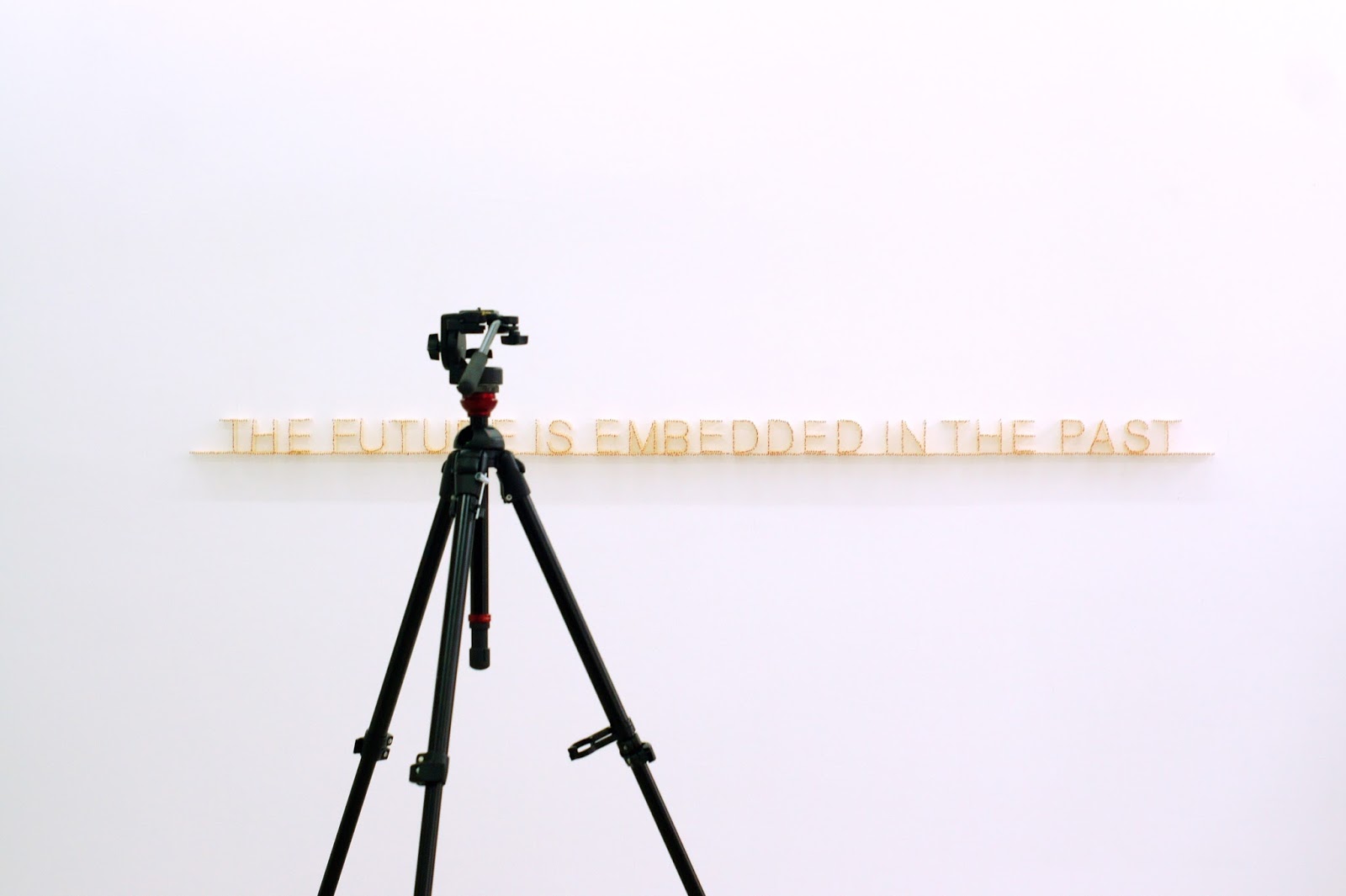

Studio Situation, series “Sketchbook” (2010)

You have applied your art career to business contexts by getting people to see parallels between art and business in terms of creativity, organization, and insight. The artworld, though, often seems wary and critical of commodification. So, first, do you think that these critical attitudes are justified? In particular, is this commodification new or more aggressive than it was before? And even if that’s true, do you think there’s anything wrong with commodifying art?

I wrote a piece about that, actually. The story is about Titian and Tintoretto, a real example of a tough market. Titian became court painter and was there for over seventy years. At one point, the young painter Tintoretto came into his studio and was expelled after fifteen days, because Titian saw him as a future competitor. Titian was very greedy and aggressive, but what could Tintoretto do, as a businessperson? So he went out into the streets, selling his stuff on the Rialto. He would also paint furniture and house facades for clients and put the payment question way at the end. Then, he got his first contracts and started negotiating. He was very flexible about the prices. The situation of art today has reached a different level, because it’s all about the market. No gallerist will care too much about your inner point of view or the personal statement you want to make. All that he thinks about is how to position you in the market. Of course to produce an aesthetic piece, you have to think of dynamic, dramatically good storylines. But if you want to make a living, you have to commoditize your work. The hierarchical aspect of the market is so strong, and it doesn’t have to do with who has the most interesting thought to share. It’s more about how to provocatively push forward a position, and of course to make a better selling on the market. A long time ago I asked myself, what if I did this for the next fifty years? If I were sitting in my studio, hoping for the big breakthrough? What would I have achieved in life? I was so fed up being the last piece in the value chain. So I made a decision to skip that, even though I love art. Whether you do a performance or you write music or a book or you draw a drawing, you create different questions and give a form to that. That’s the essence of art, and that’s my passion still.

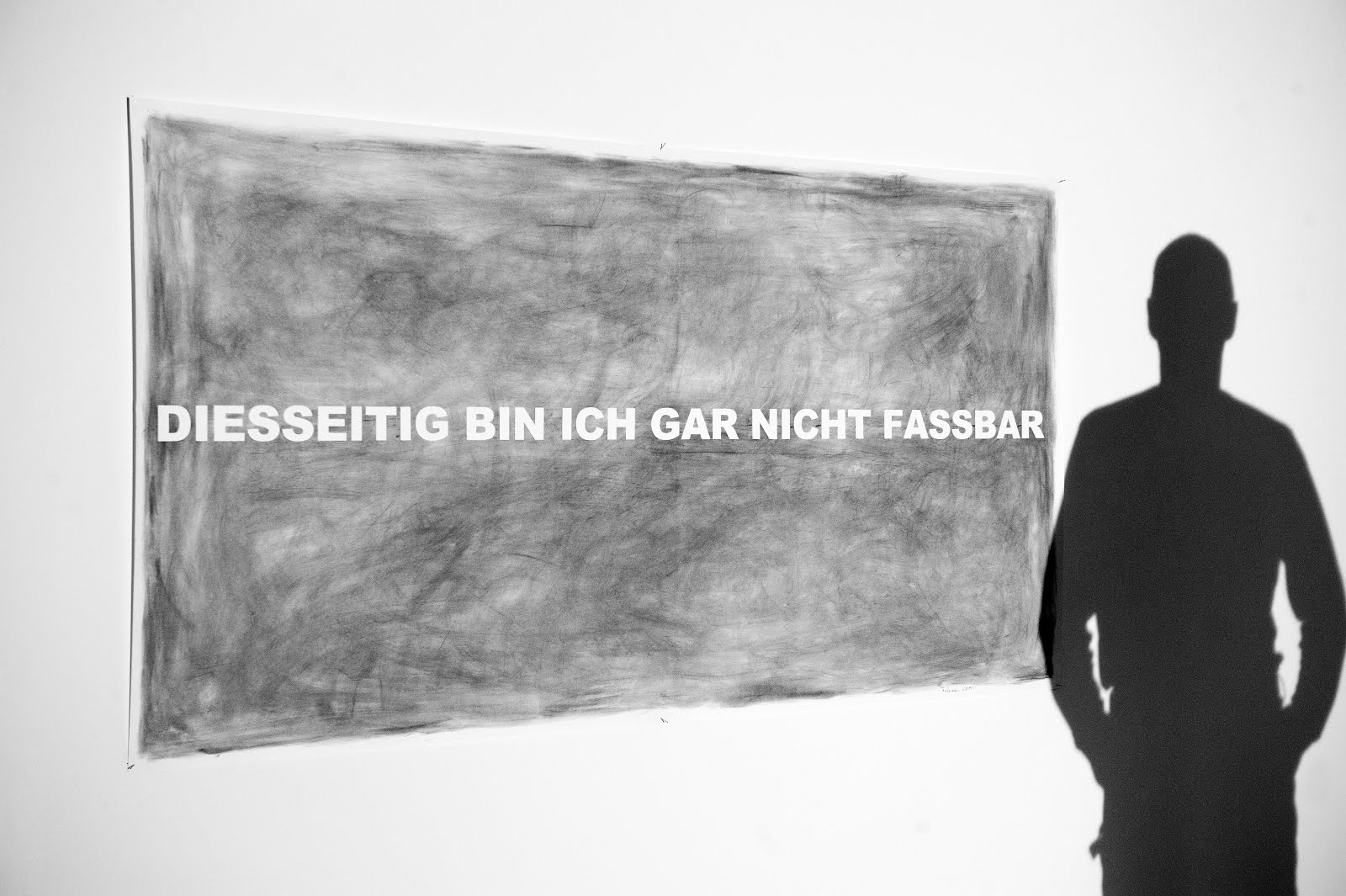

Coal drawing, series “Inflammables” (2011)

(translation: “On this side, I’m not comprehensible.”)

Second, do you see your work in business contexts as part of or contributing to art’s commodification? As a service to help people appreciate art? As, in some way, itself art?

I don’t want to offer commodification. I use examples from the artworld to talk about creative principles and tell people that’s something they can do. Every human is an artist. Every human has a creative ability. That’s what I want to unleash and focus on. If the flow of a program runs well, the best moment is when people get it. They get how we can use these creative principles for listening to other people, learning from other people, being very curious, and inspiring each other. That’s what I want to deliver.

So perhaps your work can be seen as actually decommodifying art. In philosophy, we’ve long had this idea of the artistic genius as a weird and special kind of creature, a channel for the muses, and so on. In a way, you’re demystifying what makes the art commodity so valuable, namely its contact with this special, mystical person and process.

Absolutely. There’s a nice related story about Damien Hirst. He was producing these spin paintings, where you use a round canvas and splash the color on. He had a bunch of artists producing pieces for the exhibition. One day one of the artists came along and asked if she could have a spin painting. He said, “Of course. Make yourself one, as you do every day.” And she replied, “No, I want you to sign it.” Because with his signature, it’s a Damien Hirst. Without his signature, it’s just a product. I definitely don’t want to emphasize the genius. Not at all. If you look at artists as people, most of them were awful in how they treated friends, family, colleagues, and so on – think about Picasso. It’s very rare to find examples where artists have a question that’s really related to questions we have to ask in society. Organizations are now taking these questions increasingly seriously. It’s not about producing something that’s better but meanwhile destroys nature. And interestingly, artists aren’t there at the moment. If you look from the art market perspective, it’s about pushing forward the next hot topic. To be honest, I think this is, with a broader view, it’s a waste of energy. It’s a market, that’s it. What I really want to see is how artists contribute to the question, how do we act as humans? And I think that’s a wonderful question to ask again and again.