![A title card for Frisky Dingo: On the left, the "[adult swim]" logo and show title appear in white on a crimson background. On the right, with a close-up of cartoonish, skeletal face with crimson eyes appears, lit dramatically from the left side.](https://aestheticsforbirds.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/frisky-dingo-1.jpg)

Here is a thought: as much as I like Adult Swim’s original programming, a nice chunk of it is… kinda bad. In the sense that it is often messy, teasing, testing, and many other user-unfriendly things. I mean, just to state an obvious fact about the channel that shows how challenging its experience can be: Adult Swim’s natural habitat is the middle of the night. If you watch AS during the day—like I do, to be honest—you are cheating. However, bad does not mean not worthy.

How Adult Swim Intended to Be Bad

What if Adult Swim is actually pursuing some badness by design? And what if this badness is less a matter of deficits, and more the result of a channel that asked creators to engage in non-standard strategies to build and offer audiences something unusual? I think that Adult Swim developed a “house style” of sorts, a set of recurring trademark aesthetic solutions and qualities that really expressed this attitude. Especially in the late aughts, this house style allowed Adult Swim to grow into its golden years and find its identity by pairing quirky ideas with elements familiar to those TV audiences. In this way, the programming block became a beacon for alternative comedy (animated and not), and it cemented its idiosyncratic, out-of-left-field, and even oppositional-toward-mainstream reputation.

One manifestation of this house style is something we could call “chaotic accumulation.” Chaotic accumulation led shows to purposely cram vast amounts of information in their short duration. Think about how Harvey Birdman: Attorney at Law (2001-2007) loved to indulge in crowding of all sorts: from the visual, distracting overpopulation of its frames, to the fast and bizarrely detailed development of its stories. As I see it, many original Adult Swim productions employed this style, especially those with short episode runtimes of ten to fifteen minutes. Around the same time as Harvey Birdman, other shows relied on this style, from the stuff made by comedy duo Tim & Eric to my case study here: Frisky Dingo. Frisky Dingo, created by Adam Reed and Matt Thompson (of later Archer fame), was a limited-animation show that ran on Adult Swim for two seasons between 2006 and 2008.

But before we dive into Frisky Dingo, it’s important to consider the effects of chaotic accumulation. Creators who rely on chaotic accumulation deliberately mess up the larger structures of their works. This is most clearly appreciable in relation to storytelling structures, which become densely packed with information, convoluted, wonky, uneven, and sometimes hard to manage. Especially in North American mainstream entertainment, where storytelling is king, this counts as a rebellious gesture, and one that effectively expresses the alternative vibe sought by Adult Swim. But this choice affects people watching at home. Consider how US audiences, especially those of animated comedy television, are very much used to coherent, only moderately puzzling storytelling structures. They know how to make sense of them, and they also expect various rewards for having successfully dealt with them. Chaotic accumulation upsets this whole setup based on the routine of expected pleasures, but eventually it discloses its own alternative spectatorial pleasures.

Chaotic accumulation, like other elements of the Adult Swim house style, allowed the channel and its programming to establish continuity with the mainstream tendencies in comedic entertainment, while also fashioning itself as the “alternative place.” In the case of Frisky Dingo, this dynamic was replicated in the show’s relationship with parody. This had special implications for parody’s reliance on clear, audience-friendly storytelling.

Frisky Dingo and the Idea of Parody

Even a cursory review of Frisky Dingo’s first season suggests that its comedy is mostly grounded in its being a parody of superhero narratives, aesthetic tropes, and stock characters. In this sense, the show seems to follow a celebrated tradition in televised adult animation in the United States, one that solidified itself at least since the early 1990s with The Simpsons and its more or less fortunate offspring. Before and beyond television, US parody standardized itself around masters like Mel Brooks or the Zucker Brothers. At this point, people were familiar with how parody typically operates, and we knew that its pleasures were often those of the spoof: both a mockery and a celebration of a target. However, chaotic accumulation makes Frisky Dingo an odd fit in this tradition. It allowed the show to marshal a “will to parody” without having to do anything to truly back it up. In this sense, FD is a failed, malfunctioning parody. But this is a feature of the show, not a bug.

The thing is, parodies are playful, even zany love letters to their targets. Imitation, so the saying goes, is the sincerest form of flattery, and so parodies often end up preserving and celebrating what is most dear to what they spoof. And in the context of US mainstream entertainment, what is most dear tends to be the building of coherent, manageable storytelling. Think of The Simpsons: the show’s famous two-episode saga “Who Shot Mr. Burns?” (1995) is a parody of the whodunit, especially as it was found in 1980s and 1990s soaps and dramas, from Dallas to Twin Peaks. It adheres to and upholds the narrative rules and structures of the genre, and it is thanks to this that the show can successfully play out all its comedic twists.

In the first “Who Shot Mr. Burns?” episode, for instance, The Simpsons spoofs the cliffhanger that famously ended Dallas’s “Who Shot JR?” episode. For this, Dr. Hibbert directly addresses the audience. By breaking the fourth wall, the show also parodies the pop culture frenzy that Dallas prompted.

Another Simpsons episode, “HOMR” (2001), has become a well-known example of parody that celebrates storytelling. The core narrative is a heartwarming spoof of Daniel Keyes’s 1959 novel Flowers for Algernon. In this Emmy Award-winning episode, Homer goes through a trajectory analogous to Charlie, the protagonist of Keyes’ novel.

In “HOMR,” scientists discover that Homer has a crayon stuck in his brain. Upon its removal, he becomes a refined intellectual who solves Rubik’s cubes, giggles at wordplay on NPR, and becomes the personal hero of his smart daughter Lisa. But Homer’s newfound intelligence makes him unwelcome among his peers. Crushed by social rejection, he decides to reinsert a crayon in his brain, and he explains himself in a touching letter to Lisa, who understands his choice and hugs him at the end of the episode.

Frisky Dingo, too, spoofs Flowers for Algernon with its episode “Flowers for Nearl” (2006). But the parody resides more in the hints left by the characters and the setup than in any core narrative arc. The episode raises the possibility of making a parody of Algernon and then quickly ridicules it, since the show’s characters repeatedly fail to acknowledge or pin down the source material, confusing it with—and burying it under—a plethora of unrelated, but similar-sounding pop culture references.

Not long afterward, the character Nearl—a proxy for Charlie from the novel, and also a long-lost twin brother to one of the show’s protagonists (à la The Man in the Iron Mask)—is unceremoniously killed as soon as he is given a minute of narrative exposition. There are two interesting features of this death. First, he is killed by another character in the name of narrative simplicity: a rather ironic and self-reflexive touch for a show built through chaotic accumulation. Furthermore, his death halts any potential for parody he was carrying.

I could go on. Frisky Dingo is replete with parodic elements. But creators Adam Reed and Matt Thompson dumped them on each ten-minute episode like a heavy bag of bricks. The show ends up treating us to a barrage of references and a constant shifting of its parodic targets—all things that never end up being organized into a full-fledged parody. There is mocking, heaps of it, and from habit we might think that there might be a larger joke to get, eventually. Still, its chaotic accumulation makes everything quick and non-consequential, and so the show constantly thwarts our attempts to find a larger picture. In fact, the show does more than this. It pushes us away from doing any kind of “making-sense” work, narrative or otherwise, which now feels pointless.

Chaos Reigns

In Frisky Dingo, chaotic accumulation works via interruptions. The show itself begins as an interruption, when the credit sequence of a Sealab 2021 episode (Reed and Thompson’s previous effort for Adult Swim) is abruptly halted by some signal scrambling. This scrambling resolves in a greeting from Frisky Dingo’s resident bad guy and protagonist Killface, who is taking over the airwaves to broadcast his message of doom.

Frisky Dingo bursts with interruptions, especially as it picks up a faster pace halfway through its first season, and especially in its dialogues, which carry the bulk of the show’s appeal, given its otherwise spartan looks. Characters continuously interrupt each other’s speeches and actions, fueled by sheer incompetence or obnoxiously narcissistic behaviors. As expressions of comically negative characters, these interruptions concoct a perfectly serviceable, entertaining celebration of toxic idiocy and annoyance. Because of this, Frisky Dingo episodes, at their best, feel like some sort of more sophomoric take on the Marx Brothers: all lack interest in robust solid narratives.

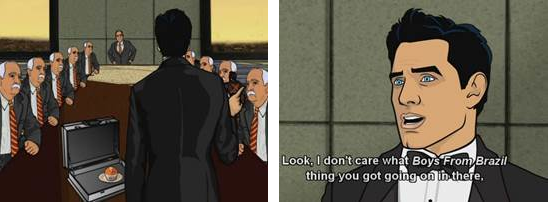

Villain Killface’s hero counterpart, Xander Crews, is a self-absorbed asshole who only cares about playing vigilante. As a result, his assistant Stan—a vague spoof of Batman’s Alfred—decides to take command of the Crews Company by filling the Board with clones of himself. Once discovered, this fact is casually and very quickly addressed by Crews as a “Boys from Brazil thing”—a reference to the famous novel and film. But, in the end, the reference amounts to nothing. It explains nothing about the clones, and it makes clear that the “clone story” does not even matter. The entire gag is then rapidly buried under the weight of all the other references that soon follow it.

Once again the intent to parody is clear in Frisky Dingo. What is jeopardized by chaotic accumulation is its deployment into a broader, traditional storytelling structure. In the first season, protagonist Killface would normally be a spoof of a generic supervillain, hellbent on destroying the Earth, while his foil Xander Crews is a billionaire with a secret vigilante career. We, experienced audiences, pick up the signals, and—encouraged by the occasional step in the right direction—we expect to be en route to a comedic rendition of the fight between the Good and Bad guys. Nope. None of that ever really comes to fruition, nothing organically grows into stable, overarching parodic storytelling.

In the end, the first season feels like a parody of a superhero narrative, but this feeling is not backed up by any actual effort toward achieving that status. The same goes for the second season, which doubles down on this strategy, though it shifts target. In fact, after a turn of events I will not spoil, Killface and Crews end up as competing presidential candidates, turning the show into what could be—but never fully turns out to be—a spoof of documentaries about US presidential campaigns, like Primary (1960) and The War Room (1993).

Chaotic accumulation allows Reed and Thompson to collect, with neither reason nor development, possible parodic scenarios: there is stuff that could be used to build spoofs of workplace narratives, as well as setups aiming for the parody of family quarrels. There are loads of casual and assorted mockeries of the woes of everyday life in the US, from private health insurance issues to consumerism and product placement. Frisky Dingo also frequently namedrops daytime celebrities including David Arquette, Jason Alexander, Fred Dreyer, and Roxanne Shanté. But all of this is gratuitous. The cultural baggage of each celebrity ultimately irrelevant and unused, sterile, pointless. Everything piles up, but no structure grows out of anything. Whatever we might confuse as structure is bound to be, above all else, simply a manifestation of our own biases: of the fact that we are used to expecting certain results if certain chords—in this case, those of spoof—are being played.

Even when some elements become recurring jokes in Frisky Dingo, they still do not provide a foundation for anything. The show’s actual story arcs, their parodic intents aside, are quasi-null. Every season finds its direction only toward the end, and by most standards, these are unsatisfying, seemingly half-assed endings. But of course, telling a story has never been the point here, and so it will be unsurprising to read that the preferred pastime of the show’s still-committed fan base is the hashing out of catchphrases, more than the celebration or dissection of meandering, convoluted plot points.

Audiences may grow frustrated by all this. The chaotic compression of information that goes nowhere blocks the show from pursuing organic and coherent parodic storytelling. Consequently, people at home might feel their spectatorial experience becoming sterile: What’s the point of following this? This is not going anywhere! As the fox in Lars von Trier’s film Antichrist (2009) eloquently states:

How to Embrace the Chaos

However, once we come to terms with the fact that chaotic accumulation is by design, and that parodic storytelling, and parody itself are not the point here, then at least two new types of pleasures open up for us as spectators.

The first pleasure transcends Frisky Dingo. We can gain a newfound appreciation for Adult Swim and the countercultural discourse that its programming promoted in the late aughts. There is plenty of quirky, offbeat, aimless, juvenile, and misleadingly amateurish humor going around these days. Think about Nathan Fielder’s work, The Eric Andre Show, Tim Robinson’s I Think You Should Leave, or Patti Harrison’s comedy writing and performances.

The second pleasure is a bit more specific to watching Frisky Dingo. Consider that the show came out in the late aughts, and that these were also the early days of US television’s more pronounced investment in complex storytelling—a trend inaugurated by shows like Lost (2004-2010). In his book Complex TV, media scholar Jason Mittell explains why contemporary television audiences are attracted by complexity, especially in relation to storytelling. He focuses on shows that use highly self-reflexive, layered, and convoluted forms of storytelling using what he calls an “operational aesthetic.” The goal of such an aesthetic is to push audiences toward a more aware and intense engagement with the “how” of a given work—here it means the “how” of storytelling, how the narrative is made to play out. The pleasures afforded by operational aesthetics prompt audiences to bask in the satisfaction of grasping the development of complex storytelling structures, over its factual contents. For example: a sizable portion of the overall pleasures afforded by the German show Dark (2017-2020) stems from how the series invites us to marvel at, and to make sense of, its brilliant management of overlapping temporal trajectories.

Film theorist Jason Gendler has recently refined Mittell’s position in an analysis of the highly parodical, compressed, and chaotically accumulated events from a 2010 episode of the television show Community (2009-2015). Gendler notes that the episode is just “too much to handle”: it is too fast and too topsy-turvy to truly lead us toward the pleasures promised by operational aesthetics. The excessive, unruly, and unorthodox use of parody in the episode forms a complex whole. But this is not the sort of complexity that Mittell discusses; it is actually a mockery of it. We end up enjoying this lack of balance and direction as a deliberate sabotage of the neatly operating complex structures in standard storytelling that we would otherwise admire.

The cognitive pleasures offered by chaotic accumulation in Adult Swim, and in particular by Frisky Dingo, belong to the broad category that Gendler writes about. Frisky Dingo evokes parody, but refrains from building it. We set ourselves up for the cognitive pleasures and traditional payoffs related to getting parody in its standard, storytelling-based forms, but then the show amuses us with its deliberate failures. In doing so, the show also highlights how much of our appreciation of mass entertainment drives on autopilot. Chaotic accumulation makes the “making sense of stories” part of our brain spin idly, offering us a chance to enjoy, rather than decry, disruption and absence. To put it in a Rube Goldberg-esque fashion: the pleasure of chaotic accumulation lies in getting that you are not supposed to get what is being promised to you, because, in the end, there is nothing to get aside from the impression of getting something. The pleasures in Frisky Dingo’s chaotic accumulation come from the frustrated process of habitually digesting and making sense of something that deliberately fails to be the typical parody that it only vaguely suggests it could be.

Now, Hellraiser’s Pinhead would say that pleasure is pleasure and it should always be pursued, no matter what it involves. Being more conservative than Pinhead on the subject, I am ready to concede that the joys of chaotic accumulation found in Frisky Dingo and most Adult Swim productions don’t immediately meet everyone’s taste. But here is a sales pitch. By trying to embrace these pleasures, one can also gain a fuller assessment of Adult Swim’s impact on contemporary alternative US comedy. Plus, the abnormal modus operandi of chaotic accumulation offers the chance to better tune oneself to the appreciation of “bad” art.

These are all outcomes that Frisky Dingo puts within reach, one needs only to humbly leave the door open to Killface and company, and to their idiotic, never-meant-to-be-completed parody. Saying no to the show from the get-go because of its idiocy or its deliberate incompleteness leads to nothing, and what’s the appeal of that? As Killface tells us, while covered in crawling ants for reasons that are of course pointless to explain: “Pride is a fool’s fortress. Now, who’s for Denny’s?”

Gianni Barchiesi is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of Film Studies at CUNY Brooklyn College and will soon join the College of DuPage as an Assistant Professor of Film Studies. In his research, he investigates the intersections between the study of the aesthetics of the moving image, and theoretical and philosophical inquiries into our perception and experience of these images.

Edited by Thi Nguyen and Alex King

![A title card for Frisky Dingo: On the left, the "[adult swim]" logo and show title appear in white on a crimson background. On the right, with a close-up of cartoonish, skeletal face with crimson eyes appears, lit dramatically from the left side.](https://aestheticsforbirds.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/frisky-dingo-150x150.jpg)