In the past year, debates about artificial intelligence have taken over public discourse.

The use of AI in art and content creation raises moral issues. Because many AI are trained on human-created samples (including Aesthetics for Birds!), artists and other creators find it exploitative, some demanding compensation. But there are others who argue that AI will help artists, especially those with accessibility needs.

It raises aesthetic and artistic questions, too. Is AI art actually even art? If it is, could it ever be good art? AI rattles our existing concepts of artistry and creativity. It forces us to rethink the fundamental purpose of art. Perhaps it spells the end of art practices as we know them.

We asked eight scholars working in these areas to comment on the current state of art and AI. Their wide-ranging reflections, from Roland Barthes and Arthur Danto to Taylor Swift and LEGO pieces spilled on the floor, try to uncover what’s most human in art, and why we should care about that at all.

Our contributors are:

- Melissa Avdeeff (she/her), Lecturer of Digital Media, University of Stirling

- Claire Benn (she/her), Assistant Professor, Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence, University of Cambridge

- Lindsay Brainard (she/her), Assistant Professor of Philosophy, The University of Alabama at Birmingham

- Alice Helliwell (she/her), Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Northeastern University London

- Adam Linson (he/him), Assistant Professor of Computing & Communications, Open University (UK) and Co-Director of the Innogen Institute (Open University & University of Edinburgh)

- Elliot Samuel Paul (he/him), Associate Professor of Philosophy, Queen’s University, and

Dustin Stokes (he/him), Professor of Philosophy, University of Utah - Steffen Steinert (he/him), Assistant Professor at the Ethics and Philosophy of Technology Section, Delft University of Technology

Melissa Avdeeff

Melissa Avdeeff is a Lecturer of Digital Media at the University of Stirling. Her research critically examines the intersections of popular music, technology, and sociality. Recent publications include work on AI music and the audio uncanny valley; Taylor Swift and LGBTQ+ allyship on Twitter/TikTok; the music ecology of TikTok; and cultural intermediaries of Lil’ Nas X in digital spaces.

Why do we listen to music? This may seem like merely a rhetorical question, but on reflection it exposes some of the debates, controversies, and critiques that the rise of AI music is facing, and our relationship to it. Regardless of the wider ethical and moral issues associated with AI art, from a more philosophical point of view, I wonder why it matters if music is composed with computational means? Are our tastes and preferences constrained to “human” creativity? Can we get to a point where an AI-generated ballad makes us cry? And does compositional authenticity matter if a song is able to provoke such an emotional response?

We are not yet at the point where someone can press play on a platform and hear a fully computational piece of music, vocals and all. But there have been recent hints at how AI might become incorporated into the music industries, and whether listeners will be able to experience embodied reactions to these productions.

As a milestone example, in April 2023 Ghostwriter released “Heart on My Sleeve”, a track with beats produced by the anonymous artist, and vocals generated in the sound of Drake and The Weeknd, overlaid over an original vocal recording, using AI voice replication software such as UberDuck. In the grand scheme of things, the use of AI was quite minimal, but the uncanny sound of Drake’s voice being replicated to such a close likeness really highlighted the potential for AI music generation tools, and for audio deepfakes.

Putting aside the copyright implications here (record labels have already tried to put a stop to AI-generated vocals, no doubt moving towards a model of in-house voice ownership and generation), what I found most interesting was how much people seemed to enjoy the track. When it was reposted on social media platforms, listeners often commented that this was better than Drake’s own songs and many wanted an official release to integrate the track into their regular listening rotation.

As “Heart on My Sleeve” gained widespread attention, controversy and critique followed, with many questioning whether this could be considered digital blackface, what it means for the future of artists, and what the human element of creativity, or musicality, actually is.

In my recent academic research, I have been examining the narratives around AI music on YouTube, at this crucial point in time as the technology is starting to become more viable, accessible, and platformed. Like discussions around AI art, one of the dominant narratives is that AI music lacks a “soul”, and therefore cannot be emotionally engaged with.

The purpose of music has long been explored. Is it integral to human development, a nuanced sociocultural phenomenon, or just something we pursue for enjoyment? The reasons why and how we listen to music are complex and highly diverse, but so are the mechanisms by which we development our preferences, and subsequently, our dislikes. There is no singular way to determine whether a piece of music will or will not resonate with audiences, so it is curious to see, at times, essentialist perspectives of AI music circulating on social media, where a frenzy of conversation tends to converge into a dominant narrative. I am not saying that no one enjoys listening to computational music, far from it as we’ve seen with “Fake Drake”, but my research strongly suggests that the dominant narratives are primarily neutral to negative.

This reaction is not unique. Almost every major technological invention in popular music production that automates a process has in some way faced heavy criticism—calls of inauthenticity, or even calls for banning—before eventually becoming convention: the drum machine, synthesizer, and autotune, just to name a few. Each of these altered the human-music-technology relationship, taking us away from what is often perceived as the “authentic” analog experience, and adding a layer of technological mediation.

From a production (and musicians’ unions) standpoint, there are arguments to be made about taking us further away form some perceived notion of authentic music, but from a listener perspective, why should this matter? If audiences engage with the music and enjoy it, is that not one of the main purposes of musical production/listening? The relationship between artist and commerce has always been complicated. But if not for that pesky capitalist system getting in the way, I imagine that the debates around technological use would be quite different.

It is not yet clear what people mean when they say that they do not think AI music has a soul. Is it that the music lacks the embodied trauma of a tortured genius artist figure? That the listener does not (yet) have a nostalgic or emotional point of reference to it in their lives? That it lacks the context of a parasocial relationship with an artist figure? Or is it merely the knowledge of the computational process that invites such a reaction? When I see these narratives, I wonder how much that knowledge impacts response, and how it may differ had one had not been informed of the computational element ahead of listening.

As computational music becomes increasingly embedded into music production and listening, it will arguably become quite normalized. Getting to the gym and hitting play on an infinitely generated playlist of songs aligned with your target BPM, with vocals by your favorite artist, is not farfetched, and probably not too far away. Our embodied reaction to music is not based on any singular factor, and creating a sense of familiarity or memories associated with AI music is not outside the scope of possibility.

Ultimately, the soul of music is not one thing, nor often the work of one person (regardless of celebrity figures, music production generally remains a highly collaborative process). Platforms like TikTok have primed listeners to recontextualize music through memes that background musicians and foreground the ways to reuse a piece of sound. Younger generations are much more likely to find value and use for AI music, whether through their own embodied responses or as the basis for new memetic material.

Claire Benn

Claire Benn is an Assistant Professor and Course Leader for the Centre for the Future of Intelligence’s MPhil in the Ethics of AI, Data and Algorithms. Her approach to AI ethics is two-fold: to use the questions, puzzles and problems emerging technology raises to make first-order, foundational contributions to normative theory and to reflect this philosophical progress back to make concrete suggestions for the design and deployment of more ethical technological systems.

A friend of mine, and published author, recently declared resignedly that she had probably written one of the last novels that had zero input from artificial intelligence. AI is indeed already becoming heavily involved in developing plot points and characters, as well as drafting, editing down, polishing up and other aspects of the novel creation process and will inevitably soon write whole books, beginning to end. As generative AIs like ChatGPT and equivalents start writing novels to any specification in terms of themes, settings, styles, and genres, will any place be left for human writers? If, as Barthes argued, “the birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the Author,” then the birth of AI-written novels seems like the last nail in that Author’s coffin.

However, there are good reasons to think that, in this new future of AI-generated literature, greater emphasis rather than less will be placed on the Author. Human-authored works embody authenticity, connection, and status in a way that will make them prized even when AI-generated works abound.

Authenticity

One thing that AIs will not be able to do is to write in an authentic way: that is, from a unified subjective experience. This is, in fact, precisely what Barthes tried to get away from: the image of literature that is “tyrannically centred on the author, his person, his tastes, his passions.” However, in the age of AI-written works, consumers’ quest for authenticity will drive the production and consumption of human-written novels. Those who will succeed in the new era will be precisely those who can cultivate a distinctive style and give their readers access to their person, tastes, and passions.

The centrality of the cult of personality in the arts can be seen through figures like Taylor Swift, whose fan base is so devoted precisely because her work is taken to be an authentic expression of her subjective experience. Her “confessional poet” style is the attraction. If Swifties discovered that her lyrics were written by another, despite not a note changing, they would stop listening in droves. Similarly, human authors will need to cultivate clear and strong personalities from which all their works can be seen to emanate. The success of this kind of author will be grounded in veracity, openness, and intimacy.

Connection

What makes photographs special is not the precision with which they capture their subject matter, but that they give a sense of proximity or nearness to what’s depicted. After all, as Susan Sontag notes, even a fuzzy photo of Shakespeare would be much more precious than a hyperrealistic painting of him, even if the latter were a better likeness. Photographs retain a trace of the person depicted. Like the depression in the cushion left by a loved one, it may not tell us much about them, but it nevertheless makes us feel a keen sense of connection.

Similarly, we might come to favour works of fiction written by human authors when that work provides a sense of connection to the author, particularly their physicality and their person. It will be the knowledge that this word was chosen by this person that will make us continue to gravitate towards human-written novels. This sense of nearness will re-establish the ‘aura’ of a work of art derived from its relationship to an authentic, situated voice. This will be heightened whenever other mechanisms of nearness can be employed. We might see a resurgence in signed copies of books, or a return to mechanical modes of production such as typewriters. Likewise, we might place new emphasis on illustrations, reproductions of handwritten notes or anything else that is an (indexical) sign of the author’s existence, humanity, and authorship.

Status

Authors will also be able to capitalise on their very humanness by embracing the lack of perfect reproducibility and the presence of imperfections in human-created work. Consider the current trend for “handmade,” “handcrafted,” and “artisanal” products. A handmade mug that is less ergonomic, structurally sound and durable than mass-produced, machine-made versions is still desirable because it is difficult to make, and because it is “one-of-a-kind.” Owning one signals the status of the owner. The more obviously uncommon (or, even better, unique) the object is, the stronger the signal.

And so, precisely as AI-written novels become the norm, the rarity and expense of human-authored works will cement their role as signals of status and wealth and become desirable as such. This might encourage a “human premium”: human-produced literature could be more expensive because part of its value is to signal what the owner can afford to spend.

So, while some might worry that AI has killed the author once and for all, it might do the opposite. The reasons that AI-written works will no doubt come to dominate—that they can be produced cheaply, easily, tailored to individual or mass tastes, reproduced effortlessly, and disseminated widely—is exactly why a space will be carved out for human-authored works. Human authors will be valued precisely because of their personality and their physicality, for the window into their souls and the glimpses of their imperfections, and for that handmade quality that renders human-made works rare and expensive. Thus, we can see that “to give writing its future,” as Barthes was determined to do, might require not the death of the Author as he thought, but rather the Author’s resurrection.

Lindsay Brainard

Lindsay Brainard is an Assistant Professor of Philosophy at The University of Alabama at Birmingham. Her research focuses primarily on explanation, discovery, creativity, and artificial intelligence.

The ever-increasing capacities of AI are raising some questions about the value of human creativity. One question on my mind is whether (and, if so, why) it would be a loss if human creativity wanes in the age of AI. To see what I mean, imagine the following:

Sage is heading off to her first year of college. She’s always loved to draw, and her parents nurtured her creativity by enrolling her in classes, taking her to museums, and keeping her supplies stocked. She believes art is important, so even though she finds it challenging to produce drawings she’s proud of, she works hard to improve. She chose her college for its strong visual arts program, and hopes to become an illustrator.

Once she gets to college, Sage learns about generative AI models like DALL-E 2 and Midjourney. She’s amazed that they can quickly generate images in her favorite style. She’s so impressed that when she comes home for Thanksgiving, she tells her parents she’s decided not to major in art because she thinks humans won’t be needed in the future of illustration. She’s not terribly sad about this. On the contrary, she’s excited about the high-quality AI illustrations she expects to enjoy in the future. She’s always liked math, so she switches her major to accounting.

By spring of her first year, Sage is perfectly happy working toward her career as an accountant. She abandons drawing, even as a hobby, and replaces it with relaxing pastimes like watching TikTok videos. When her friends ask her why she never draws anymore, she says that she enjoys both drawing and scrolling TikTok, but drawing is much harder, and spending her energy on it feels pointless now that AI can produce such visually pleasing images so easily.

Is this a sad story? From Sage’s perspective, it’s not. She appears to think the sole point of drawing is to produce aesthetically good illustrations. If she’s right about that, and she’s right that AI can produce objects that are just as aesthetically good as the images she once produced, then it seems she’d be right to think nothing about her story is sad. The world will have plenty of lovely illustrations, thanks to AI, whether Sage continues to exercise her creativity or not. But if you, like me, can’t help but find this story sad, there must be more to the value of Sage’s creativity.

I suspect that Sage has made a mistake in how she sees the value of her own creativity. Sage doesn’t realize that her creativity facilitates human connection in a way that can’t be replicated by contemporary AI models. I argue in a forthcoming paper that one value of truly creative work that current AI models cannot achieve is self-disclosure. My friend Veronica is a talented tattoo artist, and I love that every time I view her work, I feel like I understand her as a person a bit more. When you encounter an artist’s creative work, you have a chance to see how they view the world. You have a window into what they attend to, what they value, and maybe even what they stand for. If an artist stops creating art, that window closes.

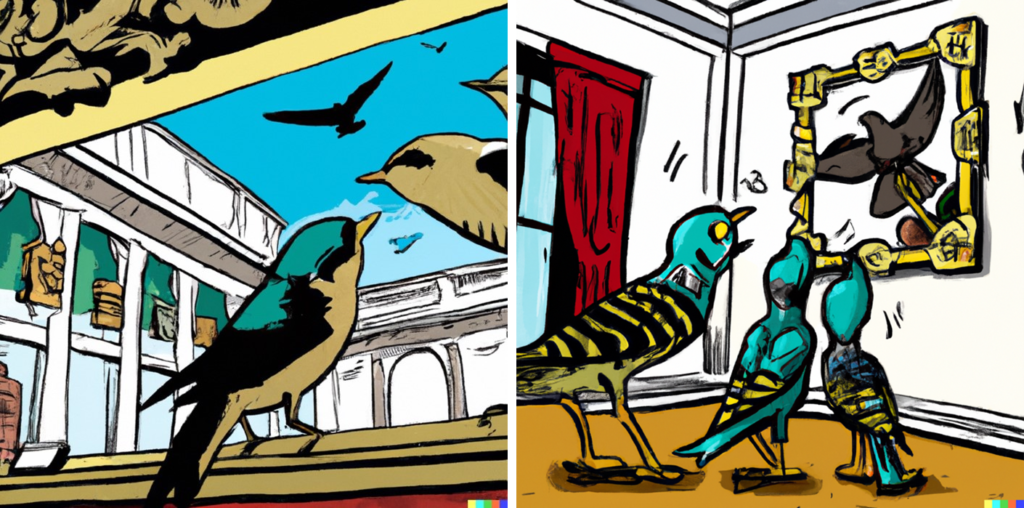

Why can’t contemporary AI models facilitate this kind of connection? Unlike Sage, DALL-E 2 and Midjourney don’t have selves to disclose. When Sage creates an illustration – say a comic-book illustration – she discloses information about her taste, her perspective, and what she cares about. DALL-E 2 can also create comic-book illustrations. Here are two it produced when given the prompt “birds enjoying an art museum in the style of comic-book illustration”:

In examining these images, what can we learn about the AI that created them? We don’t learn what it values, how it sees the world, or what it stands for. What it discloses instead is information about its technical capabilities as well as information about the sort of images the model was trained on.

If we think, like Sage, that the only value of exercising human creativity is to produce things that are new and valuable, then perhaps the emergence of AI will make human creativity obsolete. But I think this view is mistaken. The emergence of AI presents an opportunity for us to get clear on what creativity is and why it matters. If we don’t, the AI era may be one in which we gradually lose our selves without even realizing it.

Alice Helliwell

Alice Helliwell is a philosopher researching AI art, computational creativity and AI ethics. She is an Assistant Professor and Associate Director of the Graduate Research School at Northeastern University London.

Suddenly, everyone is talking about AI art. I’ve been working in this area since 2018, and in this time I’ve encountered a wide gamut of responses from the public, from artists, and from academic philosophy. What is apparent from my interactions with these various groups is the necessity for a richer understanding of AI and its use in art.

A common refrain among the general public in 2023 is that AI is stealing art. But this impulse relies on a number of misunderstandings. AI is not a monolith, and neither is the AI used to generate art. While the majority of the systems used to make art utilize machine learning, the exact structure of these systems varies. As such, the claims we make about AI should depend on the particular system under consideration. Take text-to-image diffusion models like DALL-E, Stable Diffusion, or Midjourney. Do these systems copy the work of artists? There’s no simple answer. They do not directly store or have access to the works on which they are trained (and unlike the latest iteration of ChatGPT, they do not have live access to the internet). Instead, they produce work (in part) through probabilities. As such, they cannot “collage” images, as has been claimed. Still, they can “memorize” training images when shown them repeatedly; in fact, research suggests diffusion models “memorize” images at a much higher rate than other image generation algorithms like GANs and VAEs.

For artists concerned about the use of their art without permission for training AI, these technicalities may be of little comfort. While one might hope that the lawsuits underway will help to protect artists’ work, it may not be enough to wait for law and governance to regulate the use of art for training AI systems. Policy plays catch-up to new technology, and there will be a tension between regulating AI and supporting technological innovation. However, if we consider digitized art as a form of data, then existing laws governing data can help us. Artists can take some steps to protect their own work from being used to train AI. We know, for instance, that image-detection AI can be confounded by changes imperceptible to the human eye. Because AI does not ‘see’ images like we do, making small changes to an image can have a big impact on what the AI recognizes in it, all while escaping our notice. Researchers have already developed tools that can easily apply these effects to images. Visual artists might choose to use these when uploading their works, as a form of protection against data scraping.

Some people, on the other hand, are enthusiastic about incorporating AI into artistic practice. But doing so faces another risk: AI bias. Unless the AI in question has been specifically designed with variation in mind, it will broadly replicate the kinds of things (images, sounds, texts, etc.) that it has encountered in training. We know that machine learning can be incredibly biased. This is not just in the (unfortunately) typical ways, but also in terms of cultural bias. Data gathered online is likely to be drawn from the West and is likely to be Anglophone. It will be skewed towards things that are uploaded multiple times. This will impact on the kinds of product output by the AI system, and thus the work produced by an artist using AI. So we must ask: What have these systems been trained on? And is that what we want them to continue to generate? An attitude common among philosophers and computer scientists is that AI is just a tool. I would advise against forming this judgement hastily. We are certainly using AI for our purposes, but there is much about AI systems that differs from what we might consider to be a typical artistic tool. The AI systems used can vary widely, as can their application. There is a vast difference between my simply inputting a single prompt into DALL-E, and the artists that carefully select or produce work to train their own AI system, yet both are being called “AI Art.” What is more, outputs from machine learning systems may not be fully within our control—or our understanding. Many AI are “black boxes,” where no one (not even those who designed the system!) knows exactly why the system outputs what it does. There is considerable variation in the extent to which we control the output and therefore, considerable variation in the extent to which we can be attributed with the creation of it as an artwork. And, with increasingly autonomous and generalized AI systems on the horizon, we may also need to grapple with AI becoming considerably more than a tool for human creation, and perhaps eventually assigned some credit of its own to the works it creates.

Adam Linson

Adam Linson is an Assistant Professor of Computing & Communications at the Open University (UK) who studies the flexible interplay of perception, action, imagination and memory. He is also active internationally as a double bassist, improviser, and composer.

When we engage with an artwork, we do not begin from nowhere. A number of contextual inferences guide our engagement and shape our interpretations. As philosopher and critic Arthur Danto pointed out in his seminal work, The Transfiguration of the Commonplace (Harvard UP, 1981), when we believe a piece of art is by a specific artist or from a specific time period, we interpret the work accordingly. But, if it turns out that we are mistaken about the attribution, we must revise our interpretation. This line of thinking provides an opportunity to reflect on what happens when we encounter an artwork produced by AI, but believe that a human artist was responsible. Even if we are aware of the AI origin of a work, implicit false beliefs can impact our interpretation of it.

Since we are in part dealing here with automated production and reproduction, a fitting example to consider is Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962). Warhol performed the manual labor of materially producing the work’s images by hand (he famously used other approaches in related works). Commenting on this work, the artist notes that he subsisted on that very soup during his formative decades. His comment associates the subject of the images with literal existential struggle. In addition, the work arises in the context of the artist’s practice, which spans multiple subjects, materials, and techniques, and is itself embedded in and engaged with the wider contexts of the art world and society.

Any of the above considerations could inform an interpretation of Campbell’s Soup Cans, but none of them would apply to a visually similar AI-generated work. To use a variation on one of Danto’s thought experiments, if we learned that Campbell’s Soup Cans was made by an AI system rather than by Warhol, the work would not lend itself to an equivalent interpretation. There would be no genuine implications of food for survival or effort to convey anticipated sensory experiences, no direct connection to an artist’s practice.

Our interpretation of an artwork is informed by what we take to be facts about the work. When we have a visceral encounter with an image, story, or performance produced by a typical AI system, there is an inherent continuity with our experience and knowledge of related human endeavors. Even if we are consciously aware that the inner workings of an AI system do not share a common context with human labor and culture, we cannot escape the automatic inferences that underpin our reactions: “Look what it came up with! Look what it made!” In doing this, we implicitly anthropomorphize the AI system. Yet the basis for these inferences can be traced to the human works that comprise the training corpus for the system as well as the human evaluation that actively shapes the training process.

The pithy saying that all art is plagiarism is sometimes used to mislead our thinking about the relationship between human and AI training. Artists, including in the performing and literary arts, study the works of their respective traditions, the works of their peers, and other aspects of the world around them (as Warhol did with commercial design). This leads to influences that may go unacknowledged. But those influences are transformed by artists through their particular selection of what to consider or ignore, exalt or critique, and how to go about it.

If being influenced is plagiarism, it is certainly not the kind that describes the active avoidance of costs (labor, licensing fees, symbolic status, etc.). That is, being influenced does not amount to undertaking the targeted extraction of benefits from a source, while pretending no extraction took place. Benefiting from such extraction is a form of labor exploitation, no matter one’s stance on intellectual property. The exploitation is not meaningfully changed when sophisticated machine learning is used in place of rote copying. If counterfeit objects derived from originals are seen to undermine intellectual property rights, then in a sense, counterfeit artists derived from originals can be seen to undermine labor rights.

The AI “artist” that appears as the immediate source of a work is effectively a counterfeit human artist, given how the continuities with human contexts shape our experience of its outputs. While typical AI systems are trained by associating like with like in the system’s inputs, AI deployments capitalize on how readily we associate like with like in the system’s outputs. In this way, an artwork “created by AI” is experienced as part of a human context that has an illusory independence from its training data sources. It is unsurprising that training sources are obscured in mainstream AI deployments. As with rote copying, the hiding of sources supports implicit false beliefs that impact our interpretation of a work. Those implicit beliefs suggest the AI “artist” shares more in common with humans than we explicitly know to be the case.

AI-generated works that are superficially similar to artworks in a machine learning training corpus are increasingly being presented for public consumption, in outlets including physical gallery spaces and online media. Artists whose work is used as training data face direct labor exploitation, even when they lack intellectual property rights to the work they produced. For example, a (human) graphic artist employed by an animation studio might produce a variety of character model sheets that remain the studio’s intellectual property. If the studio later trains an AI system on those model sheets to generate a new character, this doesn’t violate any intellectual property rights of the artist. But this use of AI produces additional outputs without the human labor ordinarily needed to do so, and thereby negatively impacts the artist’s employment conditions.

When AI art is produced by tacitly exploiting the labor of artists, it affects how audiences interpret that art. A false basis for interpreting a work is significant, as a valid interpretation in part depends on facts about the artist and the time period. If the work turns out to be by a different artist or from a different time period than initially believed, previous interpretations must be revised. This is equally true when a work is discovered to be a counterfeit, an active attempt to deceive the audience about the artist and often the time period of the work.

Some AI art may fall short of an active attempt to deceive the audience, as when there is some effort made to communicate how the work was produced. Nonetheless, due to the inescapable contextual inferences we make automatically, there is a latent deception embedded in underlying training processes that fine-tune the associations of like with like. The results imply an AI artist that is ultimately a thinly disguised counterfeit human artist (“Look what it came up with! Look what it made!”).

Labor issues related to AI are a major factor in the recent strikes by the WGA and SAG-AFTRA (Hollywood’s writer and actor unions), and legal initiatives by the Authors Guild (a professional advocacy group) and associated authors. There is an untapped potential for labor movements in the creative industries and for the philosophy of art to mutually inform one another on the topic of AI. Both have something to offer to how we think about the role of AI in artistic production, reception, and deception.

Elliot Samuel Paul and Dustin Stokes*

Elliot Samuel Paul is Associate Professor of Philosophy at Queen’s University. He is co-editor of The Philosophy of Creativity: New Essays (Oxford University Press, 2014) and co-author of “Creativity” in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2023).

Dustin Stokes is Professor of Philosophy at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City. He works in the philosophy of mind and cognitive science, and related issues in aesthetics. He recently published Thinking and Perceiving (Routledge, 2021).

*The authors contributed equally to this piece.

Suppose you’ve been commissioned to create artworks in response to the following prompts:

1. Studio Ghibli landscape

2. Statues

3. A Cityscape at Night

4. New Times

For each prompt, take a moment to imagine what you would produce.

Given the same prompts, another artist came up with these four images, respectively:

These works have various aesthetic qualities: perhaps dreamy, haunting, spooky, dazzling, lovely. You’d probably think the artist was creative in making them.

But the “artist” is an AI system called VQGAN+CLIP. You can take it for a spin yourself. Upon learning this, you will probably continue to see these images as having whatever aesthetic qualities you observed before. But you might hesitate to call the computer program creative. Why? (You may also resist calling these pieces ‘artworks’, but this is a distinct question: there are non-creative artworks and creative non-artworks.

According to the standard definition in psychology, creativity is simply the production of things that are new and valuable. (Click here for our survey of the literature.) These AI images are new and have some aesthetic value. So, they are creative on the standard definition, and the fact that they are produced by an AI system makes no difference at all. And yet, learning that fact might give you pause.

You are right to pause. The standard definition must be missing something because creativity is not merely about new and valuable products. When water molecules crystallize to form a snowflake, the result exhibits novelty (no two snowflakes are identical) and aesthetic value (they can be quite beautiful). But water molecules aren’t creative, and that’s because they are not agents – beings who are responsible for what they do. Genuine creativity is an expression of agency.

This leaves open the question of exactly how agency must be exercised in creative acts. One proposal is that the act has to be, in some sense, intentional. Suppose you have embarked upon the (entirely futile!) task of organizing your child’s many thousands of LEGO pieces. Partway through the process of attempting to organize by color, size, shape, function (again, futile! Don’t try this at home!), there emerges an interesting and colorful, chaotic but seemingly patterned, array of pieces. The pattern is new and has aesthetic value, but you weren’t creative in making it – not to mention that it does nothing to serve your organizational task. The pattern was a lucky coincidence. You didn’t know about it or intend to produce it.

We are reluctant to call water molecules creative for the same reason we are reluctant to call you creative in your organization of the LEGO pieces. “Creative” is a term of praise, and we do not extend praise or blame for things that are not done by an agent, or for things that an agent does accidentally rather than intentionally. Genuine creativity requires intentional agency.

Creativity also tends to involve spontaneity and surprise. Squaring this with agency and intentionality is one of the most interesting challenges of theorizing creativity. This “puzzle of creative agency” is a guiding theme in our forthcoming book Creative Agency.

This explains our hesitation to call AI programs creative. The question isn’t whether such systems produce things that are valuable and new – they clearly do. The question is: Are these systems genuine agents?

There are reasons to think the answer is no. If a program or app does something offensive, for example, we don’t hold it responsible. So it doesn’t seem to be a moral agent. Nor is it a legal agent. At least at present, these systems are not being legally credited through patents, ownership, or copyright. Finally, these systems are not “caring” agents. In philosopher John Haugeland’s colourful phrase, they “don’t give a damn” about what they do.

AI programs may be genuinely creative. But it is not obvious that they are. They clearly produce things that are valuable and new, but that just isn’t enough. In fact, these systems arguably pass a variant of the Turing test: you may have been fooled initially into thinking the images were the immediate product of a human hand. But the Turing test is meant to determine the presence of intelligence, not creativity. And, sadly, intelligence doesn’t entail creativity. Creativity is, necessarily, an expression of agency. And it simply isn’t clear that AI systems such as these are agents.

Steffen Steinert

Steffen Steinert is an Assistant Professor at Delft University of Technology. His research and teaching focus on the philosophy and ethics of technology, particularly philosophical discussions and theory-building about values and technology.

Artificial intelligence can be a boon. It makes many things easier and faster, including the creation of art. All you need is a computer with an internet connection, and you can use DALL-E to generate images and Magenta to create pieces of music. Art is at your fingertips!

AI-generated pieces have aesthetic value and have already won prizes and art competitions. Although some praise the rise of AI in art creation, many share my suspicion that something is off about AI art. And I am not talking about denying machine-generated pieces the status as works of art. Even if we grant them this status, something doesn’t feel right about them.

This feeling has to do with the fact that achievement is a crucial factor in why we appreciate and value works of art. Achievement matters to us, and the effortless AI-enabled art creation is achievement-undermining. To understand the claim that AI undermines art as achievement, we must address two sub-questions: What is achievement? And why does achievement matter?

What is achievement? Consider some examples. Finishing a marathon, mastering a new language, and getting a Ph.D. are achievements. These involve a deep commitment, sacrifice, competence, and skill. Achieving something means competently bringing something about, which is difficult and takes effort.

Most artworks are artistic and creative achievements in this sense. Becoming an artist requires effort. Many artists commit to the craft by spending considerable effort and time to acquire artistic competence. For instance, they begin formal training at a young age or spend years studying traditional techniques and honing their craft. Creating a piece of art also requires effort, time, and sacrifice. An artist must invest time and attention. They must also be persistent in the face of obstacles. All this effort enhances their achievement.

Why does achievement matter? For one, achievements are a crucial part of a meaningful life and meaningful work. Similarly, achievement is essential for a meaningful life as an artist. Achieving something contributes to a positive self-conception and is a source of pride for the artist. People are proud when they have achieved something. Achievement and effort also make certain attitudes appropriate. We admire artists for their persistence and for their commitment to the craft.

Achievement also contributes to the artistic value of a work. We value works of art because they are beautiful or otherwise aesthetically pleasing. But we also appreciate works of art because their creation involved considerable effort, competence, and skill. We value works of art because their creation involves effortful commitment and competence. Some even claim that excellence of skill and achievement is necessary for the status of a work as art. The use of artificial intelligence in art creation probably doesn’t diminish the art status of a piece, but it certainly makes that art less of an achievement.

Using automation and AI in producing art creates an artistic achievement gap. Who should we assign artistic credit to? Artistic achievement and effort matter; giving artistic credit to somebody for making a few clicks seems inappropriate. We may still celebrate it as a collective achievement and a form of collective authorship. We would distribute achievement between multiple collaborators, including software developers and engineers. The widespread use of AI in art creation may contribute to a culture of suspicion where viewers and listeners suspend their artistic appreciation. Even worse, they may dismiss every work they encounter as lacking achievement.

Achievement matters for our appreciation of art and the value of art. The use of AI is achievement-undermining. Making machine art is the opposite of competently creating something difficult that takes effort. AI enables the creation of works of art without effort, skill, and sacrifice. Making a few clicks may involve some effort, but this hardly counts. An AI-generated piece would still be art, but it would not be an achievement.

Roundtable introduced and edited by Alex King

November 27, 2023 at 1:26 pm

I. can’t make the print larger, therefore don’t know whether your participants’ commentaries make sense or not. Puts any comment from me out of the conversation, doesn’t it? Do better, or I will erase you from consideration.