An essay by Antony Aumann (Northern Michigan University)

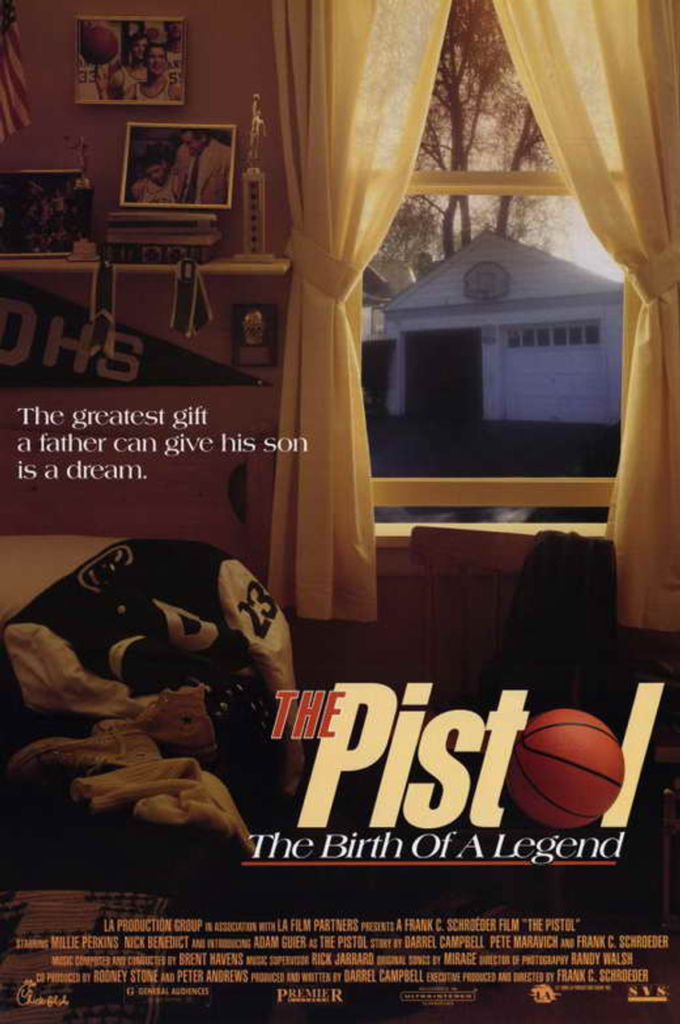

I was twelve when I saw The Pistol: The Birth of a Legend, a biopic about the basketball star Pete Maravich. It wasn’t a good movie—think Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis, but a lot cheesier and focused on shooting hoops—so I’m somewhat embarrassed to admit that it had a significant impact on my life. Watching it inspired me to spend my teenage summers dribbling a basketball in the driveway, hoping to become a star myself.”

My parents still tease me about those days, and I admit I was being kind of silly. But not that silly. People are inspired all the time to do things because they see them on TV or in the movies. Arnold Schwarzenegger decided to become a bodybuilder after seeing Reg Park play Hercules, and Mae Jemison chose to become an astronaut after watching Lt. Uhura in Star Trek. In addition, many students major in forensic science these days because of CSI. The phenomenon extends beyond careers and professions. Karate Kid sparked a martial arts boom in the 80s and Rocky prompted a revival in boxing. Similarly, Cheryl Strayed’s Wild led many people to seek peace on the Pacific Crest Trail, and Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat, Pray, Love served as a catalyst for spiritual tourism in Bali.

So, what was silly about my teenage hoop dreams? Here’s one answer: I was being gullible. Movies and TV shows wouldn’t inspire us if we didn’t trust them. They wouldn’t get us to change our lives if we didn’t think they were revealing something important about the experiences in question. But should we trust movies and TV shows? The question is laughable. Of course not!

After all, many movies and TV shows are fictional, and fiction is a poor guide to reality. Pipetting might seem fun and fascinating on CSI, for example, but in actuality it’s a tedious task that’s easy to screw up. Plus, even works of non-fiction, like the memoirs of Strayed and Gilbert, are trying to entertain us. And entertaining us is frequently at cross-purposes with telling us the whole truth. At the very least, the boring bits have to be left out. Finally, almost all movies and TV shows depict how things go for other people. And we seldom have good reason to think things would go the same way for us. Perhaps The Pistol revealed what Maravich’s childhood was like, but he was an exceptional talent and I was not.

These points are so obvious that trusting movies and TV shows does start to sound a bit silly. Or at least a bit childish. Indeed, it’s no coincidence that it’s children who are most often inspired by what they watch. It was a young Arnold who was moved by Hercules and the Captive Women and a young Jemison who was moved by Star Trek. It was also a young version of myself who was transformed by The Pistol.

Yet, it isn’t just children who are inspired by the screen. Think of how we adults respond to advertisements. We see a group of people having fun in an Applebee’s commercial, so we bring our family there the next weekend. We see a good-looking model in an oversized pair of Gucci sunglasses, so we buy a pair for ourselves. It isn’t children who are making these decisions. It’s also not children who choose to hike the Pacific Crest Trail after seeing Wild or take a vacation to Bali after watching Eat, Pray, Love.

Are we all being silly? Answering this question requires thinking harder about why we trust movies and TV shows. Sometimes it’s because we have evidence that they contain a kernel of truth. For instance, we hear corroborating testimony from someone who’s gone through the experience themselves. But this is rare, and it doesn’t capture what’s usually behind our trust in movies and TV shows. In the typical case, we aren’t relying on evidence. We’re relying on a feeling or an intuition. Arnold talks this way. He says he could just see that Reg Park’s life would be his life. That’s also how I felt about Pistol Pete. When I watched him on the screen, I just saw myself.

Is it wise to trust our feelings and intuitions? We certainly do trust them a lot. Think about first dates. When we meet the other person, we make a snap judgment. We don’t pause to consider the evidence; it’s a gut-level thing. The person feels like a match or they don’t. Sometimes we use visual metaphors here. We accept or decline a second date because we can “see” ourselves with the other person or we can’t. Jobs are like this too. We hire or pass on potential employees based on whether we could see ourselves working with them. Intuitions also guide our more mundane decisions. We buy a shirt or put it back on the rack because the vibe is right or wrong.

Of course, that doesn’t answer the question. We do trust our feelings and intuitions, but should we? Maybe! We wouldn’t have survived as long as we have if our feelings and intuitions were totally unreliable. Humans would’ve died off long ago if the basis for most of our decisions was a horrible guide to reality. So, we can trust our instincts about the people we meet and the situations we encounter because those instincts have been honed over millions of years.

That story sounds good. Unfortunately, the empirical science points in the opposite direction. It’s increasingly clear that our feelings and intuitions are plagued by biases. This is a well-known problem in the case of hiring practices. The gender, race, and attractiveness of a candidate shape our sense of whether they’d be competent, even though these factors have nothing to do with job performance. Our predictions about ourselves aren’t much better. We’re particularly bad at forecasting whether we’d be happy or sad if we had this or that experience. Moreover, and crucially, we’re not bad in just any old way. We’re bad in that we’re idealistic. We succumb to wishful thinking: we predict what we’d like to happen rather than what’s likely to happen.

This helps explain our reactions to movies and TV shows. Why did I once think I’d look like Don Draper from Mad Men if I wore the same suit? Because that’s how I wanted to look. Why do my forensic science students believe their lives will be as fun as the ones depicted on CSI? Because that’s how they wish their lives would go.

Maybe this misses the point, though. When watching a movie or TV show, we don’t always believe things will go for us as they do for the characters on the screen. In fact, we usually don’t even think it’s likely. We just think it’s possible. This matters because the mere possibility of an outcome can be enough to justify its pursuit. Think again about dating. We might know it’s unlikely that the person we’re asking out will say yes. But as long as there’s a chance, it’s often worth a shot. (That’s the not-so-dumb lesson of the Dumb and Dumber meme.) The same logic lies behind our reactions to Wild. Someone else found enlightenment while hiking the Pacific Crest Trail, so we might too. Are we sure? No. But it doesn’t hurt much to try!

Not all cases fit this pattern. Sometimes we have a strong intuition about a movie or TV show. We don’t just think what we see on the screen could happen to us. We think it will happen to us. Arnold talks this way about seeing Reg Park. He just knew his life would unfold the same way. I thought the same thing when I saw Pistol Pete: I just had this confidence that I’d become like him.

Is that attitude foolish? It depends. On the one hand, thinking my life would look like Pete Maravich’s was classic “over-believing.” My confidence in this outcome outstripped the evidence at my disposal. It was obvious that I didn’t have the physical gifts to make it. So, I was being irrational. On the other hand, irrational confidence can be quite helpful. We often can’t perform our best unless we really believe in ourselves. And we often can’t really believe in ourselves if we stick to the evidence. Here’s a basketball example. Russell Westbrook thinks he’s the best player in the NBA. He’s not. But if he didn’t have that level of irrational confidence, he would’ve become a much worse player than he turned out to be.

It’s not just performance that’s like this. Some research suggests the emotional quality of our experiences also tracks our expectations. If we believe something will make us happy or sad, it tends to do so. Thus, all those forensic science majors aren’t being silly. It behooves them to believe their futures will be as enjoyable as the ones they see on TV. Believing this helps make it true!

So, are we never dupes? Is it always wise to trust movies and TV shows? That seems wrong. But maybe there’s a way to defend the idea. Let’s start by considering a likely case of dupery: the story of Pistol Pete and me. I didn’t believe following in Maravich’s footsteps was merely possible. I thought it would happen: I thought I’d become an NBA star. That was illogical. I believed because I wanted to believe, not because I had good evidence. Now, it’s true that my irrational belief got me farther than I would’ve otherwise gotten. But that still wasn’t very far: small-town high school basketball. So, my parents’ teasing seems justified. It really was silly for me to spend my youth bouncing a ball out in front of our house.

However, in middle age, I’ve settled on a comeback to my parent’s ribbing. At least I went for it. Maybe I didn’t get there. But success isn’t the only thing that matters in life. There’s meaning to be had in striving—in passionately pursuing something we love even if we don’t win out. In this regard, Camus was right: “the struggle to the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart.” That’s why we should celebrate the power of movies and TV shows. It’s one of the few things capable of inspiring us to go for it. Maybe it doesn’t always achieve this effect honestly. Maybe it doesn’t always move us by telling us the truth. But so what? Getting fooled isn’t the worst thing in the world. In fact, the real mistake is trying to make sure we’re never fooled. Skepticism and suspicion turn us into tentative and uptight people. And when we go through life like that, we miss out on a lot of meaning and happiness. We’re better off being silly in the end, even if it means getting teased now and then.

Antony Aumann is a Professor of Philosophy at Northern Michigan University. You can learn about his research by visiting his website or follow his art on Instagram.

Edited by Alex King