What follows is a roundtable discussion of the new book Philosophy of Comics written by Sam Cowling and Wesley Cray.

To do philosophy of comics is to engage with everything from philosophical aesthetics to cognitive science, from moral philosophy to the history of mass art, and from complex debates in metaphysics to nuanced issues in the ethics of representation. It’s in this spirit that we wrote Philosophy of Comics: An Introduction (Bloomsbury, 2022), and it’s in that same spirit that we’ve looked forward to engaging with the range of philosophers, comics scholars, and artists who graciously agreed to collaboratively engage in this roundtable. (Enormous thanks are also due to Matt Strohl for pulling this roundtable together.)

First, a lightning quick overview of our book! Our goal is not to explore philosophy through comics—that is, using the medium as a lens through which to tackle perennial philosophical questions—but instead to explore, expand, and fortify the growing field of philosophy of comics: that is, philosophical examination of the medium itself, as well as its relations to other social and artistic phenomena. For that reason, the book covers a lot of ground, ranging from social questions (e.g., the ethics of comics pornography, the norms of re-coloring) to artistic questions (e.g., how to approach the relation between comics and literature or the aesthetic evaluation of comics adaptations) to ontological questions (e.g., what kinds of artifacts comics are, what kinds of entities fictional characters are) and more. Our hope is that philosophers will find interest in the investigations into comics, and that comics creators, scholars, and fans alike will find interest in the philosophical explorations.

Our contributors are:

- Nicholas Whittaker, PhD Candidate at CUNY Graduate Center (they/them)

- Sam Langsdale, Independent feminist scholar (she/her)

- Henry Pratt, Associate Professor of Philosophy at Marist College (he/him)

- John Holbo, Associate Professor of Philosophy at the National University of Singapore (he/him)

- Eike Exner, Historian of Comics (he/him)

- Roy Cook, John M. Dolan Professor of Philosophy at the University of Minnesota – Twin Cities (he/him)

- Austin English, Artist and writer (he/him)

- Author’s response from Sam Cowling and Wesley Cray

Nicholas Whittaker

Nicholas Whittaker (@nwhittaker10) is a PhD candidate at CUNY Graduate Center. They work primarily at the intersection between continental phenomenology, philosophy of art, and black studies. Their publications, released and forthcoming, include essays on black horror film, philosophical duplicity, digital blackface, H.P. Lovecraft’s racism, abolitionism in popular culture.

Sam Cowling and Wesley Cray’s Philosophy of Comics: An Introduction is not the first book written on the subject. In fact, it’s hard to believe that philosophical investigations into comic books have reached the point where a book like this one can be written: a dizzyingly comprehensive catalog of very nearly every philosophical question that one could pose about this mass medium, with no need to flagellate over the supposed crassness of its subject, no self-aggrandizing or apologetic justifications for its own existence, and no gratuitous fretting over questions like “What are comics?” and “Are comics art?” Instead, Cowling and Cray get to pack as many deep, broad, minute, grandiose, subtle insights and interrogations into these pages as possible.

This book and its investigations matter, but they may do so in ways Cowling and Cray don’t even acknowledge. To see this, I want to point to those majestic, silly creatures called superheroes.

Cowling and Cray spend a lot of time talking about cape comics. But for the most part, superheroes are used as case studies for more general philosophical issues, without much need to define or fully explicate their superhero-ness. And when Cowling and Cray do turn to such definitional work, they wisely avoid biting off more than they can chew in a dense overview text like this one, spending a little more than five pages on the subject.

However, one alternative theory to their own might have massive consequences for a theory of comics (not least because it could compel us to center superheroes in that theory). This is the theory developed by comics writer and pop philosopher Grant Morrison.

For Morrison, superheroes are not one kind of fictional entity among others. Rather, superheroes fulfill a genuinely unique, and rather essential, narrative role. Superheroes, as Morrison melodramatically (but, perhaps, no less accurately) puts it, play the narrative roles that gods do. Superheroes are secularized gods.

This view of superheroes—let’s call it the Supergods View (after Morrison’s book proposing this theory)—isn’t suggesting that people believe in superheroes like they believe in gods. Nor is it stating the obvious, that superheroes exhibit godlike behaviors or abilities within their fictions. Rather, Morrison is trying to argue that oddly ubiquitous and emotionally resonant events like the murder of Bruce Wayne’s parents are not like other fictional events, even similarly well-known ones (like the death of Sherlock Holmes). Rather, they work—at a narrative, and in some sense psychological and emotional level—like the rebirth of Osiris did in myths of old.

I’m not brave, or foolhardy, enough to try to explain this fully here. But I think it’s incredibly worth it to try to figure out how to; the stakes are quite high. We can see how thanks to a concept Cowling and Cray discuss frequently: medium specificity. Medium specificity picks out the fact that comics can do unique formal and aesthetic things (things that movies, novels, and paintings can’t). For example, panels (as opposed to, say, frames) only exist in comics. Or, a more relevant example: some scholars have suggested that superhero costumes might only work in comic form. When photographed, or described verbally, they may lack the iconicity they possess in comics; they might even look downright laughable.

Intriguingly, many of the features that Morrison thinks make superheroes godlike are specific to comics. For example, they would cite Batman’s extensive canonicity, or the ease with which new stories are added to it, or the character’s arrested development and that of his world, or his visual simplicity and iconicity, etc., as features that make him godlike. But these are all features of comics Cowling and Cray extensively discuss, and either argue or imply are specific to comics! But that could mean that superheroes wouldn’t be godlike without these features, which are, once again, specific to comics. In other words, reading Morrison and Cowling and Cray together seems to suggest that superheroes are godlike because they come from comic books, and that they may not have been godlike if they had come into their own in other media, like paperback novels or television serials.

Again, allow me to sheepishly wave away understandably probing questions like “How?” The point is that if the Supergods View is right, then comics might be very, very special. If superheroes are fictional entities that serve the role that gods do, and if that role is made possible by features specific to comics, then comics might be rather weird, and quite exciting. Could this medium have some particular, special fictional power? Do comics uniquely manifest a particular human capacity—telling stories about gods—that has proven to be a massively important capacity throughout history? If so, then this book—and the future musings I hope it prompts—have consequences a lot more far-reaching than one might have assumed.

Sam Langsdale

Sam Langsdale is an independent feminist scholar whose work focuses on the cultural politics around representation of gender, sexuality, and race in visual culture. Her research on comics has appeared in peer-reviewed journals and award-winning edited volumes. She is particularly proud of being the co-editor of the multi-author book Monstrous Women in Comics (University Press of Mississippi). Her forthcoming monograph From the Margins into the Gutters: Searching for Feminist Superheroes is under contract with The University of Texas Press. You can read more about Sam’s work here: https://www.samlangsdale.com/

In Chapter 7, “Representing Social Categories in Comics,” Cowling and Cray examine the various vices—aesthetic, moral, epistemic—that mar representations of characters in relation to social categories in comics. One specific criticism they explore is “the moral viciousness of superhero comics” owing to “the genre’s narrative structure” (200). They write that “the very nature of superhero stories themselves perpetuates social injustice insofar as superheroes essentially function to keep society at, or restore it to, its present status quo. In so doing, works within the superhero genre affirm the moral acceptability of a society marked by a variety of inequities and injustices” (200). This is not inevitable, of course, Cowling and Cray are careful to note that the entire genre is not necessarily determined by this narrative tendency. The authors acknowledge that superhero comics that do not seamlessly align the status quo with the moral good and that feature superheroes who “actively work against objectionable features of a prevailing social order” do exist.

This point is of particular interest to me as a scholar committed to searching for feminist superheroes. Resonant with Cowling and Cray’s analysis, feminist theorist Lillian S. Robinson argued that although many contemporary superhero comics have increased the numbers of powerful women in their pages, they have generally done so in a way that ignores ongoing, real-world gender inequity, racism, and heteronormativity. That does not mean that feminist superheroes do not or cannot exist, but for Robinson, representations of feminism in comics would not simply need to depict “a ‘present time’ where gender equality flourishes and where accusations of discrimination are baseless,” they would also need to show “us how such conditions came to pass” (2004, 138). I argue that one salient example of such a text is Harley Quinn: Breaking Glass (2019) by writer Mariko Tamaki and artist Steve Pugh.

Harley Quinn, a main character in the DC comics universe, was originally created as a humorous female henchwoman, intended to appear only once in Batman: The Animated Series. After becoming a recurring character on the show, she was reimagined as a sidekick and love interest for the primary male antagonist, The Joker. This biography carried over into her debut in comics in 1999 and remained the dominant narrative for many years. Eventually, she became a supervillain in her own right and left her toxic relationship with The Joker, but her character design remained persistently androcentric. It was not until the 2010s that comics began telling Harley stories that imagined her as entirely independent of The Joker, that connected her to other female characters in meaningful ways, and that departed from the heteronormative status quo of the genre. However, while these changes arguably ameliorated “the moral viciousness” of Harley’s character history, few comics have revised her story in such thoroughly feminist ways as Tamaki and Pugh’s retcon graphic novel.

Set in Harley’s early teens, Breaking Glass imagines the antiheroine arriving in Gotham after a childhood full of poverty, familial strife, and an already long rap sheet. This backstory decouples Harley’s criminality from ableist, classist assumptions about her inherent “craziness” and instead makes it clear that her record is the result of a justice system which caters to and protects the rich. In fact, Breaking Glass repeatedly demonstrates the intersectional failures of white supremacist, capitalist, patriarchal, heteronormative societies (a.k.a., the status quo). For instance, when villainous wealthy white developers set out to gentrify Harley’s neighborhood, it is her found family—queer drag queens of color—who are impacted the most. Tamaki and Pugh’s attention to the lives of their diverse cast of characters reveals to readers that Harley’s drag queen family is vulnerable not only because of their marginalized social positioning, but also because of a history of loss. The eviction plot thus acts as a recollection and critique of “the process of intense gentrification that New York faced during the years 1981 to 1996, when the AIDS epidemic swept through the City”.

Equally important to the book’s ability to highlight the problems with the status quo is its emphasis on various ways to change it, none of which, Harley discovers, involve blowing stuff up. At school, for example, Harley and her friend Ivy stage a protest intended to evoke the work of the feminist activists The Guerilla Girls in response to a sexist extracurricular club. Even though Harley and Ivy’s first protest does not induce the change they seek, their efforts are not in vain. Other students are inspired by their efforts and ask to take part in future demonstrations, echoing the real power of protests to draw attention to a cause and to mobilize a group. While I am not prepared to argue that Breaking Glass is entirely free of the vices Cowling and Cray discuss, even these brief examples affirm the authors’ assertion that “there is no compelling reason to believe that morally vicious social representation is unavoidable within the superhero genre” (202).

Henry Pratt

Henry John Pratt is an Associate Professor of Philosophy at Marist College. His research encompasses frivolous issues about artistic value and comparability as well as more serious topics about horror and facial hair. His book The Philosophy of Comics: What They Are, How They Work, and Why They Matter is forthcoming with Oxford University Press in spring 2023.

When I was asked to contribute to this roundtable discussion of Cowling and Cray’s Philosophy of Comics: An Introduction, I agreed immediately. It’s a fine book, treating a variety of important philosophical problems about comics with informed care. The authors even demonstrate excellent judgment in citing my work several times. Their failure to cite my book, which bears a title unnervingly similar to their own, is unfortunate, mainly because it confirms that Cowling and Cray don’t have access to a time machine. My book won’t be out until Mat.

As I considered the rich possibilities for what to post on here, I thought about what really draws readers, and the answer came back to me immediately: porn. At great personal sacrifice, I boldly skipped all the spellbinding, tedious metaphysics in Philosophy of Comics: An Introduction and went right for Chapter 9: “Comics, Obscenity, and Pornography.”

Toward the end of the chapter, Cowling and Cray consider—and, I think, tentatively endorse—the idea that the media employed to make pornographic comics amplify the moral value of the pornography therein. When pornography is inegalitarian (i.e., eroticizes the oppression of women and other disadvantaged groups), comics can make matters worse, since the process of understanding a comic mandates the reader’s complicity in imaginatively connecting the events depicted in the panels. However, there’s a bright side: comics can make positive contributions through egalitarian pornography (which empowers members of traditionally oppressed groups and treats them with dignity and respect). Comics is (standardly) drawn, neatly sidestepping the moral risks inherent in photographing actual humans engaged in sexual acts. Moreover, comics can easily, effectively, and inexpensively depict a range of sexual preferences and body types that lie outside what’s typical in pornography, serving the needs of a diverse array of readers “without necessarily objectifying or instrumentalizing any real persons” (p. 273).

Granting that most of the foregoing is correct, I wonder about something that Cowling and Cray don’t take up. Comics can be used to make egalitarian pornography. But should it? Below are three reasons why not.

1) Even so-called egalitarian pornography is morally problematic. OK, so this isn’t a popular opinion within the academic circles in which you’re likely to run if you’re reading this. But blanket criticisms of all forms of pornography are not unheard of. From a leftist, feminist perspective, Catherine MacKinnon is still at it. And right-wing criticism of all pornography is abundant and culturally significant. From this perspective, it’s a mistake to think that any pornography is empowering rather than oppressive, since it inherently involves violence, coercion, prostitution, addiction, adultery, and sin. Arguably, then, if the effects of pornography are enhanced when put in the form of comics, that’s a real problem. Should comics with pornographic elements of any type be met with moral enthusiasm if they’re potentially complicit in, e.g., sex trafficking and eternal damnation?

2) Back in the mid-20th century, figures such as Sterling North (1940) and Frederick Wertham (1954) gave voice to a general cultural hysteria about what comics were doing to children, which resulted in book burnings, Senate hearings, the notorious CCA, and so on. Nowadays, their worries—which, as Cowling and Cray point out (p. 251-52) were mainly about crime and horror comics anyway—might seem quaint and outdated. But check it out: the very qualities that allow comics to amplify the moral effects of pornography are also the effects that make them awesome for kids to read. The pictures in comics offer the possibility of conveying content easily and engagingly to beginning readers or even those who are wholly illiterate, especially in comparison to purely verbal literature. Anecdotally, if I’m reading a comic around the house, my kids will want to get a peek, no matter what it is, but they’re never interested if I’m reading a salacious novel by, e.g., W. Somerset Maugham. Why does any of this matter? Well, if we’re going to promote egalitarian pornography, do we have to do it via an artform that’s great for kids? Can’t we promote egalitarianly pornographic operas or something?

3) Cowling and Cray (p. 273) raise the possibility that egalitarian pornography serves the aim of expanding its consumers’ sexual preferences and tastes to encompass persons and bodies not deemed to be attractive by the standards established and maintained by conventional pornography, advertising, and other popular media. Comics could be especially good for this since they allow readers to explore new things without needing to encounter any other real people. Maybe so, though I expect the effects are only notable once they get transferred to real people. But that’s not the worry. Picture the stereotypical construction worker who thrives on cat-calling women he perceives to be attractive. Somehow, he gets ahold of some pornographic comics, in the egalitarian vein. They help him realize that all sorts of people, regardless of sex, race, gender, body morphology, facial structure, foot size, etc. are attractive in their own wonderful way. He proceeds to cat-call everybody. Is that a good result?

This is a blog post. I’m just asking questions. I’ll leave it up to you to decide whether any of them ought to be taken seriously.

John Holbo

John Holbo is Associate Professor of Philosophy at the National University of Singapore. He has published “Redefining Comics” and “Caricature and Comics” (self-archived versions). His first foray into comics was Squid and Owl. He likes to mix cartooning and philosophy. He has written Reason and Persuasion, an illustrated introduction to Plato. He tried to turn Nietzsche’s Zarathustra into a Dr. Seuss-style children’s book. That got daunting. Now he’s trying to cartoon 100 philosophers. He’s up to 60-something. (He’s lost count.) He tweets at @jholbo1. He blogs at Crooked Timber (but he used to blog more).

Let me toss three questions out for discussion.

First, is there too much philosophy in the philosophy of comics, hence in The Philosophy of Comics, an Introduction?

What kind of rude question is that? A tough but fair one, I say. From page two of the book:

“Apart from its distinctive focus on the medium of comics, philosophy through comics is therefore quite similar to other projects like philosophy through film or philosophy through science fiction that use works within a specific medium or an entire genre as a launching point for philosophical inquiry.”

If I may insinuate myself into the target zone, I regularly teach “Philosophy and Film” and “Philosophy and Science Fiction”. I do a Virgil thing, you might say. You know, from Divine Comedy: the power of reason poops out early. Teaching film, I often have the feeling, and often give into it, that the edifying thing to do is assign—oh, say—another sprawling New Yorker film review by Pauline Kael, rather than picky-picky analytic-style paper.

On the other hand, the science fiction course goes great insofar as the thing about science fiction is that it’s plain true that the stuff is built to be philosophical. The golden age of mid-century science fiction is short fiction that substantially aspires to the status of thought-experiment. But film—it gives me dilemmas. (I can declare Kael a ‘philosopher’, but I’m not such a sophist.)

Comics seem to me more like film than like science fiction. Cowling and Cray collide with this. For nearly forty pages, they wrestle with the definition. They arrive at ‘why’—why are things comics?—and correctly observe that an extensionally correct definition of ‘comics’ wouldn’t be it, even if one could get it, which is overly optimistic. This is philosophically important to see, but it turns a chunk of the book into a red herring, comics-wise.

I am curious about others’ thoughts and feelings about this, i.e., the diminishing returns of analytic-style philosophy of comics.

Speaking of which, they write:

The reception of philosophical work within comics studies has been peculiar. Those describing comics studies hasten to tout its interdisciplinary nature, but only rarely is philosophy among the list of disciplines cited as contributing … in Hatfield and Bart Beaty’s recent edited volume Comic Studies: A Guidebook (2020), which aims to provide a snapshot of the state of the art of this interdisciplinary field, no philosophers are included and the work by Cook, Meskin, and almost every other philosopher of comics goes uncited and undiscussed … We suspect, for example, that philosophers’ focus on extracting and making explicit arguments, theories, and theses will strike some outside of philosophy as stifling.

As someone anthologized by Cook and Meskin, I prefer being read. But I sympathize with the impulse to ignore us. The problem isn’t that arguments are stifling. The problem is that scholastic tendencies have diminishing returns.

I don’t mean to bash philosophy. Truly. I retract the label ‘scholasticism’ if that irritates. Call it ‘Socratism’. We philosophers have a keen sense you can Socratize anything. But how sure are we that that’s always interesting?

Two more questions—quick hits. The second is a follow-up to the first. Page six reads:

In keeping with the contemporary analytic tradition, our focus is on explaining phenomena as clearly as we can and then offering arguments for and against competing theories that seek to explain these phenomena … While it might be exciting or enlivening to be presented with provocative but opaque claims about comics (everything is a comic! nothing is a comic!), we believe that there are more and less plausible views about comics and that rigor and clarity in argument offer the best way to discern them.

My intuition is the opposite! (I say this without animosity.) Here’s a counter-thesis: There’s no profit wrangling ‘what is comics?’, analytic style, unless you are arguing for a radically revisionistic conception. For the only way a discussion of definitions will be insightful—edifying—will be by affording some new view.

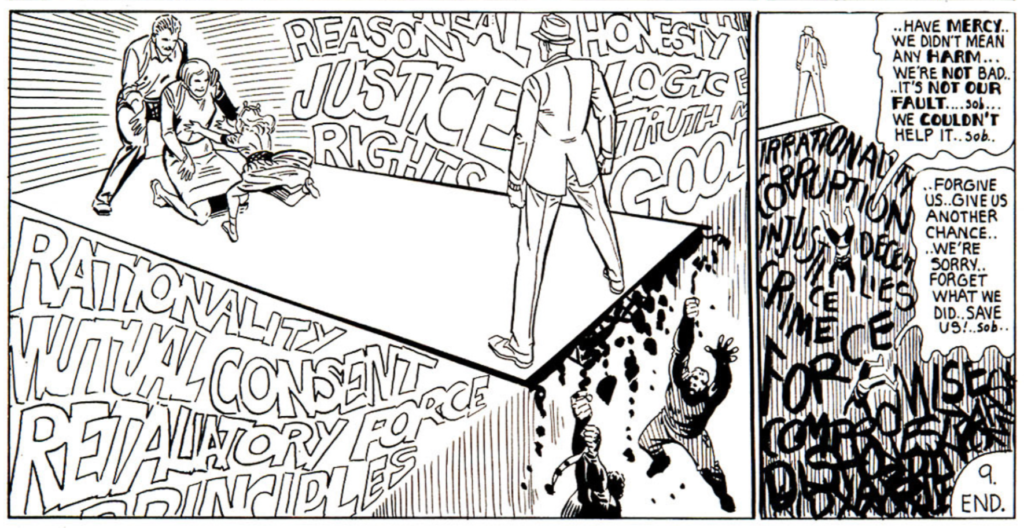

Third, let’s talk Mr. A.

On page one of the book we see Mr. A doing his Ditko thing. If you don’t know, A is a vehicle for Randian Objectivist philosophy but it comes out a good deal stranger even than that makes it sound. That blank mask, upright poise and solemn diction makes him seem like some herald of Galactus—if Galactus were Reason. And if Reason turned out to be a libertarian.

Their questions, then, don’t seem to me like the right questions to ask about Mr. A. They ask (I’ve added numbers):

1) What account of rationality would vindicate Mr. A’s view that reason requires him to kill the kidnappers?

2) Does our willingness or reluctance to view Mr. A as a hero indicate that his methods are morally objectionable?

3) Is the implicit premise of Mr. A, that criminals are beyond redemption, remotely plausible?

But they asked, so here are my answers.

1) A surreal account.

2) Obviously Mr. A is the hero. That’s just genre. But, actually, if we don’t view his methods as insane, it’s we who are nuts.

3) No, the premise is goofy. It’s perfect that Mr. A first appears in Wally Wood’s Witzend.

The questions Cowling and Cray pose are not wrong, then, but they’re playing it too straight. Mr. A isn’t so much a thought experiment. He’s more what Ursula K. Le Guin called a “psychomyth.” Hence Alan Moore’s correct decision to turn him into Rorshchach—a walking Rorschach test.

Mr. A prompts thoughts on rationality. I agree, but in a ‘sleep of reason breeds monsters’ way. So framing Mr. A as posing dilemmas about rationality is a bit like treating Kafka’s “Metamorphosis” as “What Not To Do If You Turn Into A Bug” self-help. Mr. A is outsider art, philosophically, weirdly.

Plato has Socrates say: I ask these questions to discover if I am a simple creature or a many-headed monster. Wrapping back to my first question: How successful do we feel the analytic-Socratic approach to comics is at bringing out how simple creatures, like Mr. A, suggest that we readers are strange monsters?

In conclusion, this philosophy of comics business risks falling between two stools, per two remarks in Novalis’ Logicological Fragments, I.

63. The eye is the speech-organ of feeling. Visible objects are the expressions of the feelings.

64. The meaning of Socratism is that philosophy is everywhere or nowhere—and that with little effort one could get one’s bearings through the first available means and find what one is seeking.

Eike Exner

Eike Exner is a historian of comics and the author of the Eisner Award-winning Comics and the Origins of Manga: A Revisionist History. He also translates old Japanese comic strips on his Instagram account @prewar_manga. Follow him on Twitter at @eikeexner

In graduate school I once considered taking a course called “Philosophy of Language,” offered by the Philosophy department. The instructor warned me, “This might be a little different from the way you talk about language in Comparative Literature.” She was right. I spent much of that first class session wondering, “Why this focus on defining words? What’s the objective?” (I later found out that this is called analytic philosophy and constitutes the predominant type in Anglophone philosophy departments, and that what my mainland European self had thought of as “philosophy” was actually continental philosophy.)

Reading Philosophy and Comics transported me back to that philosophy class. As the first chapter summarized various approaches of defining comics, only to find each one inadequate, I kept asking myself, “What are the stakes? What if we do manage to define comics perfectly? What then? Will there be cake?”

Don’t get me wrong, I’m a big believer in defining terms. It is way too common to find writing on the history of “comics,” “cartoons,” “manga,” etc. that neglects defining what it’s talking about and ends up mixing together objects under the same label that are actually quite different. But I’m afraid that comics, like virtually all categories, is a “social construct” in that it means different things to different people, which renders a universally acceptable definition impossible. I for one believe that it doesn’t make sense to refer to anything pre-1899/1900 (when modern speech balloons began to spread) as a comic, and that the average person would agree with me on this, but I nonetheless have to substitute the more cumbersome term audiovisual comics for comics so that I can communicate with people with more expansive definitions. Likewise, a fellow historian recently told me about a “comic” he had found, adding at the end, “I guess you’d call it a picture story, not a comic.” Such is life.

Cowling and Cray dismiss social constructionism—the idea that the meaning of words is determined by convention—with an aphorism ascribed to Abraham Lincoln: “How many legs would a cat have if we called a tail a leg? Four. Calling something a leg doesn’t make it one.” Lincoln is surely right that even if we all started calling a cat’s tail a leg, there would still be an anatomical difference between the first four legs and the fifth. But let me try some analytic philosophy of my own: Why do cats have four legs and humans two? After all, our arms are anatomically analogous to other mammals’ front legs. Is it because we mostly walk on two, cats on four? If I tied my cat’s forelegs to a set of wheels, would she then have only two legs? Are humans born with four legs, two of which then change into arms? Or is it about the presence of opposable thumbs? But we call the front limbs of theropods (T-Rex and such) “arms” and they don’t have opposable thumbs either. And what about animals that alternate between quadripedal and bipedal locomotion? It would appear that the question of what’s a leg (and by extension, comics) isn’t quite as simple as Abe Lincoln would have us believe.

Let me offer a proposition: what if we defined comics not in absolute terms, but as an archetype? Cowling and Cray write that non-English terms that respectively translate to “speech balloons,” “little boxes,” or “drawn strips” are “potentially misleading,” but I would argue that they’re actually quite elucidating. A drawn series (strip) of little boxes featuring speech balloons after all is pretty much the answer you’re likely to get if you ask a random person to describe a typical comic. So we could say that the archetypical comic will look something like that, and that you can add or subtract elements to/from that archetype that will alter the percentage of people who’d still consider the result comics. It doesn’t mean that one side will be right and the other wrong.

Lastly, I can’t help but quickly nitpick two claims that the historical record contradicts: first, comics—audiovisual comics—did not develop as a “hybrid” medium that combined text and image (see here and here). Second, the origins of Japanese comics actually are not at all distinct from the Euro-American lineage (see here, here, and here again, and also this book).

Roy Cook

Roy is CLA Scholar of the College, Setterberg Fellow, and Professor of Philosophy at the University of Minnesota – Twin Cities. He works primarily in the philosophy of logic, the philosophy of mathematics, and the philosophy of (especially popular) art—sometimes all at once.

Cowling and Cray’s The Philosophy of Comics: An Introduction is an exceptional contribution to the philosophy of comics—exceptional enough that I have chosen it to be the central organizing text in both my Freshman seminar and my graduate seminar on the philosophy of comics in Fall semester 2023 (although of course it will function rather differently in the two courses!) Thus, any small criticisms to be found in the paragraphs below should be understood against my overwhelming gratitude to the authors for having provided us with the first (and likely for a long time the best) comprehensive monograph on the philosophy of comics! Now, on to the philosophy!

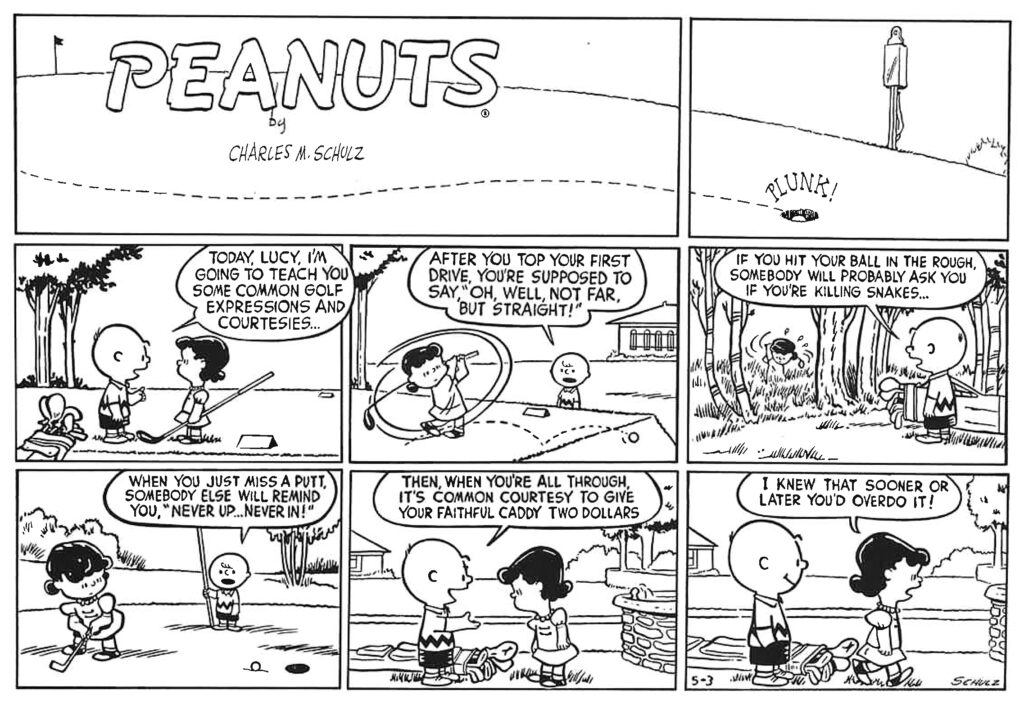

Comics are a multiply-instanced art form: you can (in some sense) fully experience the masterpiece that is Charles Schulz’s Peanuts by reading the instances that appear in a reprint volume, and I can experience that same greatness by having read the original strips in my local paper. But it is important to ask when two instances are instances of the same work, in the (or a) relevant sense, and when they not.

There are a number of different things we might mean by “the same” here. Since this roundtable is inspired by Cowling and Cray’s Philosophy of Comics: An Introduction, let’s start with two that they identify (at least implicitly). In Chapter 3 (“Comics as Artifacts: Ontology and Authenticity”), they argue that a particular instance is an authentic instance of a comic if and only if it was produced by means of the relevant template (p. 80), which entails:

Authentic Instance Identity:

Given comic instances κ1 and κ2, the comic authentically instanced by κ1 is identical to the comic authentically instanced by κ2 if and only if κ1 and κ2 were produced mechanically from the same template.

This principle holds that what makes a comic authentic is that it is made from the original template, which entails that reprinted comics are not (typically) authentic instances of the original comic. Later in the same chapter they note that, while the notion of an authentic instance is what is relevant to our collection/curation practices, a looser notion is relevant to readerly practices. On their account, any reasonably accurate reproduction can provide us with readerly access to the comic:

For most readerly purposes, a look-alike comic is just as viable a means for reading a comic as the original (p. 86)

Call this:

Readerly Access Identity:

Given comic instances κ1 and κ2, the comic that κ1 provides readerly access to is identical to the comic that κ2 provides readerly access to if and only if κ1 and κ2 are sufficiently (relevantly) similar.

This just means that a reprint is close enough to count as an instance of the comic for readerly purposes. All this is fine. But it misses a third, more important, identity-related question. Consider the Fantagraphics reprint of the entire run of Peanuts. The Fantagraphics staff, along with Canadian cartoonist Seth, who edited the series, searched far and wide to find quality copies of each strip, locating original art, printing templates, and well-preserved newspapers. Thanks to the horrifying lack of any sustained attempt to properly archive and preserve newspaper comics, they were unable to find a complete copy of the May 3, 1953 strip in time for the printing of Volume 2 (covering 1953–1954). As a result, Volume 2 contains a “reconstruction” of this strip, with the top tier being redrawn by Seth. Later, a quality copy of the May 3, 1953 strip was located, and was included at the end of Volume 4.

Clearly, the instance in Volume 2 and the instance in Volume 4 are not authentic instances of the same strip, since they trace back to distinct print templates. On the other hand, it is equally clear that these two instances provide readerly access to the same comic. Keep in mind that Peanuts Sunday strips were designed so that the top tier could be left out without affecting the gag, so that the strip would take up less space. Many authentic instances appearing in newspapers on May 3, 1953 were missing the top tier altogether.

But something is clearly missing, because there is a difficult “sameness” question raised by these instances. The inclusion of one version of the top tier in Volume 2, and of another version of the top tier in Volume 4, entails that these instances generate very different aesthetic experiences. In addition, one instance is a collaborative work, while the other was authored solely by Schulz. Instances of the same artwork prima facie have the same author(s). But neither of these considerations convince me that these instances involve distinct artworks (although they don’t convince me that they don’t involve different artworks either). Thus, when considering these instances we should ask whether they provide us with access to the same comic artwork.

Thus, what we need is a principle that provides us with something like identity conditions for artworks accessed by particular instances of a comic. That is, we need something like:

Artwork Access Identity:

Given comic instances κ1 and κ2, the artwork that κ1 provides access to is identical to the artwork that κ2 provides access to if and only if… ????

I leave filling in the proper identity conditions for comic artworks to the reader. Good grief!

Austin English

Austin English is an artist and writer living in Brooklyn. He is the co-managing editor of The Comics Journal and co-curates The New York Comics Symposium with Ben Katchor. As a cartoonist, he has published the books Gulag Casual and Meskin and Umezo. His artwork has been exhibited in galleries throughout the United States, including Marvin Gardens in New York and Et Al gallery in San Francisco. His comics and drawings have been reviewed in Art in America, Bomb Magazine and The Huffington Post. He runs the comics publishing house Domino Books, which he founded in 2011. He also teaches comics, drawing and art history at both Parsons School of Design and The School of Visual Arts in New York City.

To understand what comics are, we first have to ask: how are they made? Are they made differently from other visual mediums? They can be made in groups (these are the ones most people read) but they can also be made alone, by one person. What does this mean? Can they be made more cheaply than paintings or film or animation? Painting can be made alone, but the paint is expensive, and the fumes require space. Ink and paper escape from all this.

Do people from all kinds of backgrounds that are excluded from film and painting due to cost flock to comics? Yes and no. Why? Does it have to do with comics tendency to outwardly define itself as extremely rule based? Are there ideas of what a comic is and what a comic isn’t? More so than other mediums? This may be true. Does film welcome experimentation, vagueness, dissonance, unapologetic artistic indulgence? Maybe not at the box office, but certainly beyond that.

Comics, you might say, don’t simply ignore postmodernism—they are skittish even at mere modernism. The dregs of an uncomplicated Errol Flynn ambiance still waft around the mediums self conception. Why? Commercial concerns dominate here, more than anywhere else. Again, why? Is it because the people that gravitate to the medium come from modest means and trained themselves on cheap pencils? If so, did they bring that earned talent into a medium where the money they made wasn’t enough to sustain them beyond the next day (much less the day after that) and so they quietly submitted to the bland reliability of genre, time after time, because the formula guaranteed work? Is a medium that can be open to all and attracts those with little else also closed off to allowing all to say anything worthwhile in it? So often: yes.

But beneath the surface, the true wild and radical potential is unmistakable, even (especially) in the most hopeless cross hatching on a hack job. The shabby lines have undertones of conscious hopelessness, i.e., actual human expression. Once you see it there, you see it everywhere, waiting to assert itself. It won’t be on the bookshelves exactly (maybe a page or two by mistake in an insurgent anthology that made it through), it won’t often be in the magazines that ‘get it’. You’ll see it more clearly within a work cobbled together by hand incorrectly, where everything is done wrong and the images need to be looked at over and over to be made sense of, no adherence to the rules of communication, not out of defiance to the standard but out of knowledge that it doesn’t matter. In this medium especially, it does not matter and (more precisely) should be defied if there is ever to be an art form made by all.

Authors’ Response

Sam Cowling (he/him) is associate professor of philosophy at Denison. University. He writes about metaphysics and the philosophy of comics.

Wesley D. Cray (she/they) used to be a philosophy professor but she does other stuff now. A lot of that other stuff is done under the name ‘Ley David Elliette Cray,’ which can get confusing. The two-name thing is complicated. Anyway, you can read about her work in philosophy and aesthetics, along with her work on gender and sexuality, at leydavidelliette.com.

It always feels nice when people read your work. Sometimes it feels nice when people engage with it, too—though academics can be an unpredictable bunch. We both take the range and depth of criticism in the above responses to be deeply affirming: it’s pretty darn cool when such a fantastic group of scholars shows such a range of reactions about which part of your book is most exciting to engage with, or even—as in some cases—most tempting to dismiss.

Whittaker probes the relationship of superheroes to the comics medium with formidable depth and acuity. We’re gratified they found our book to be a useful tool for thinking through superhero aesthetics in an age of (apparent) superhero saturation. If superheroes afford us certain kinds of distinctive storytelling possibilities, are these possibilities inextricably tied to the comics medium? We confess to being uncertain, but agree that medium-insensitive engagement with superhero aesthetics tends to be oddly impoverished. In his pitch for the never-realized series, Twilight of the Superheroes, Alan Moore offers a potential counterpoint to Morrison’s secular gods take: “one of the things that prevents superhero stories from ever attaining the status of true modern myths or legends is that they are open ended.” When it comes to history and insight, a full philosophical understanding of superheroes must be accompanied by digging in the dollar bins of comics history and reconstituting the debates among the Moores and the Morrisons.

Continuing on the thread of superheroes, Langsdale explores a crucial topic in the book: the representation of social categories (and, in the case of this discussion, social philosophies) in the comics medium. This is a topic that goes beyond the detailed metaphysics and complex questions of language and cognition, and makes direct contact with contemporary social, personal, and political issues. Among other things, it shows that the philosophy of comics is useful not just as a proving ground for various more “technical” philosophical disciplines, but is also relevant and potentially impactful to individual lives. Through her discussion and feminist reading of Harley Quinn as she appears in Breaking Glass, Langsdale deftly demonstrates that theoretical issues in the philosophy of comics cannot and should not be divorced from close readings of comics themselves, and that the twin fields of philosophy of comics and philosophy through comics are perhaps more intertwined than our book suggests.

As one of us is—along with being a comics scholar—a certified sexuality counselor making a living as a sexuality educator in both clinical and non-clinical contexts, we’re glad that Pratt chose to focus on one of our favorite chapters: the one on pornography and obscenity in comics. While spirited, though, neither of us find Pratt’s concerns particularly concerning. No studies have shown any significant causal connection between consumption of egalitarian pornography and moral failure that stands up to critical scrutiny. The claim about the medium’s suitability for children seems to generalize to other media like film and photography, and the concerns about the cat-calling construction worker strike us more as concerns about a particular cat-calling construction worker than about comics per se. Finally, while we wouldn’t quite agree that Catherine MacKinnon is an accurate representative of much of the contemporary “feminist left,” it’s notable that her conception of pornography smuggles moral failure into the definition itself. If that conception wins the day, we’re happy to cede the word “pornography” and instead shift our discussion towards erotica—the term MacKinnon uses for what the two of us and others have called egalitarian pornography.

At first glance, Holbo’s contribution might seem to be a request for less clarity and a plea to value implausibility. We would be content to leave readers with those particular demands for the book unsatisfied, especially given our hopes for its use in classrooms. More credibly, it’s a call to entertain potentially surprising views about the medium—which is done pretty consistently throughout the book. We are also happy to grant this much: if the two of us have done our job with this book, it should regularly remind readers of specific comics and what it’s like to read them. Of course, since (most) comics are more fun to read than (most) philosophy, we can’t begrudge anyone who finds themselves putting our book down to go look at Frank Robbins’ original art or thumb through the new translation of Moto Hagio.

Exner’s criticisms offer us an opportunity to clarify our view since the position we defend throughout the text is a social constructionist view in that we take the category of comic to be a social and artifactual kind demarcated by creative intentions and the norm-governed activity of picture-reading. His objections are a useful reminder that, while philosophers of comics might be eager to excavate the actual process of social construction, other scholars might be content to simply affirm their commitment to social construction and leave the philosophical analysis undone. There is a possibility, however, that our divergence here stems from a disagreement about what “social constructionism” amounts to. In his response, Exner reports taking such a view to be one according to which the meanings of words are determined by social conventions—which seems to be a semantic thesis. In contrast, this book takes up a robustly conceptual project, informed but not exhausted by the anthropological linguistic project of collating the many ways in which the word ‘comics’ gets used.

Cook digs deeply and inventively into the history of the comics medium—and into our efforts to make sense of the various comics practices—to present a thorny Peanuts puzzle. Can there be significantly different comic instances (e.g., that differ in their creators and the experiences they generate) even while they provide access to the same comics artwork? One thing is clear from Cook’s case: distinguishing—as we do in the book—between collecting and reading practices surrounding comics does not, on its own, address all remaining issues about comics identity. Our inclination is to claim that reading practices are substantially more coarse-grained than collecting ones, leaving it indeterminate how many Peanuts strips we have on hand. In this particular case, given the in-principle detachability of the top tier, our hunch is that there might be three comics in play: the main strip (which appears in Volume 2 and 4) and two different “topper” comics. Carving up comics in this way arguably squares with the historical occurrence of toppers as regularly detachable and often quite different from the main body strip (e.g., Herriman’s earliest Krazy Kat appears below his earlier Dingbat Family). Of course, even if we’re correct in this case, Cook’s point stands: reading practice is a messy business that still needs sorting out.

English’s contribution returns us to the project of understanding what it is to make comics. It’s difficult to overstate the significance of the physical nature of the comics medium if there is any hope of having a philosophy of comics worth its salt. This means, among other things, that uncovering the histories of paper, printing, distribution, and—most essentially—(re)production is essential. As is argued in the book, the ethics of recoloring comics can’t be understood without situating the work of the comics colorist from the 1980s in a lengthy production process. There is much left to be done on this front and there’s no limit to how rich philosophical engagement with the production of comics might be. Finally, English’s diagnosis that comics as a medium is “skittish at mere modernism” aptly summarizes the peculiar ways in which comics get critically discussed and the barriers to understanding that can emerge when rich theory obscures some of the practical realities of the medium. There is, as English’s remarks indicate, much that can be learned about craft and history of comics from its creators and few sources are more illuminating than old interviews with cartoonists like Jules Feiffer, Gil Kane, and Marie Severin.

The philosophy of comics remains largely unexplored, and the two of us are optimistic about its current and future directions. We thank the contributors and editors of this roundtable for collaborating in the spirit of moving this still small field forward.

January 26, 2023 at 5:15 pm

Thanks for all this. I tweeted a thread in follow-up response, for such aesthetic birds as tweet. https://twitter.com/jholbo1/status/1618765082246414336

January 26, 2023 at 5:22 pm

For such birds as doesn’t, here’s my tweet thread in blog comment form.

My contribution seems negative – like I didn’t like the Cowling & Cray book we are all reviewing. Hence this response from the authors: “At first glance, Holbo’s contribution might seem to be a request for less clarity and a plea to value implausibility.” That’s not quite it. I liked the book fine but it reminded me of troubles I myself have as a teacher, especially with “Philosophy and Film”. Frankly, the very best film writing (IMHO) isn’t by (analytic-style) philosophers, writing on film, so maybe assign more Kael, less Cavell and Carroll?

But then I’m not ‘doing philosophy’, am I? Another way to put it: how helpful is ‘socratism’ for generating insight about … pop culture stuff. Example: Cowling & Cray wrangle defining ‘comics’ for forty-or-so pages before concluding (you saw this coming) that it’s elusive.

My suggestion: it’s almost never profitable going to the technical bother unless you are going to offer up a radical, revisionist definition as the logical one (despite it looking weird, on its face.) Ahem.

https://www.academia.edu/21189532/Redefining_Comics

It’s not that you have to insist on revisionist, let along implausible conceptual contours, per se. But, in pop culture contexts, socratism is seldom helpful unless serving as a means to that end. Otherwise you end up with one’s regular old concept of whatever but overly machined. No harm in it really. But kind of a weird way to run the railroad. (There’s a story about Wittgenstein trying to build his house, you know, plainly & functionally – no distracting ornament! And he drove the builders to tears, specifying all that exactly, beyond their capacity.)

One exception: lots of non-philosophers – e.g. comics studies folks – talk a lot of nonsense about philosophy in passing. They do! And you can for sure feel free to point that out, just like Socrates would. Same for film. Film studies people say the darnedest things. But that ends up being sort of negative and limited, just shin-kicking. In a positive sense, in a pop culture context, what is a good way for philosophers to deploy their characteristic intellectual aptitudes and practiced logic chops to steady, profitable effect?

I should add. I exchanged emails with Cowling about my contribution and I think we understand each other. It’s all good. We’re good.