Hagia Sophia was built during the reign of Justinian I in the 6th century. It is the most impressive building ever created by the Byzantine empire. Until the 13th century, it was the most important church in Eastern Orthodox Christianity. Back then, presumably no one imagined that Hagia Sophia would ever be anything other than an Orthodox church. Yet its last days as a church were now more than five centuries ago.

If transformative experiences are possible for things made of brick and stone, Hagia Sophia has had its share of such experiences. There have been at least five moments at which Hagia Sophia was radically repurposed. The first was when crusaders from Western Europe sacked Constantinople in 1204. They converted Hagia Sophia from an Eastern Orthodox church into a Latin Catholic church where they crowned their new emperor. The next was in 1261, when the crusaders were removed. Some semblance of the old Byzantine order was restored, and Hagia Sophia was reverted to its earlier status as an Eastern Orthodox church. Then in 1453, after having gone through a period of decline and abandonment, Constantinople was conquered by the Ottoman Turks, led by Mehmed II, and Hagia Sophia was converted into a mosque. It remained a mosque until the 20th century. Then, in 1923, the Republic of Turkey replaced the Ottoman state. The founder of the Republic, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, was an active reformer who held a secular vision of Turkey’s future. As part of that vision, he decreed that Hagia Sophia would be converted from a mosque into a museum. In recent decades, religion in Turkish political life has taken on new complexities. The role of Ataturk’s secularism is in a state of flux. A movement to revert Hagia Sophia to a mosque emerged and succeeded. It became a mosque once again in July 2020.

The recent conversion of Hagia Sophia into a mosque created controversy and anxiety not only within Turkey but all around the world. Hagia Sophia is designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site. It is meaningful to at least two of the world’s major religious traditions: Islam and Christianity. Its status as a museum was a symbol of secularism. To some, its reversion to mosque status is a step back into a dark Ottoman past. To others, it is a step forward into a brighter future in which Ataturk’s legacy will be modulated by a new role for religion in Turkish political life. For this roundtable, we recruited six scholars to explore the meaning of this event.

Our contributors are:

- Belgin Turan Özkaya, Professor of Architectural History, Middle East Technical University

- Helen Frowe, Professor of Practical Philosophy and Knut and Alice Wallenberg Scholar, Stockholm University

- Derek Matravers, Professor of Philosophy, The Open University, and Fellow of Churchill College, Cambridge

- Selin Ünlüönen, Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in Art History, Oberlin College

- David Killoren, Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Koç University

- Ege Yumusak, Ph.D. candidate in Philosophy, Harvard University

The Crisis of “Cultural Heritage”

Belgin Turan Özkaya

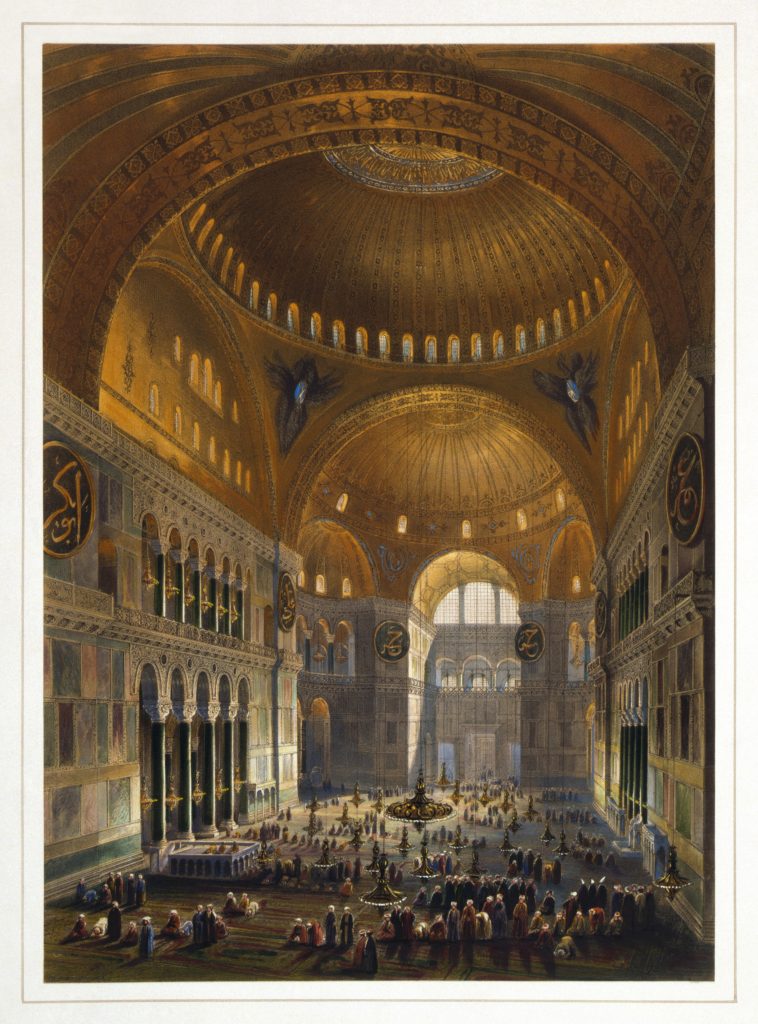

Şevket Dağ (1922), Ankara Resim ve Heykel Müzesi [source]

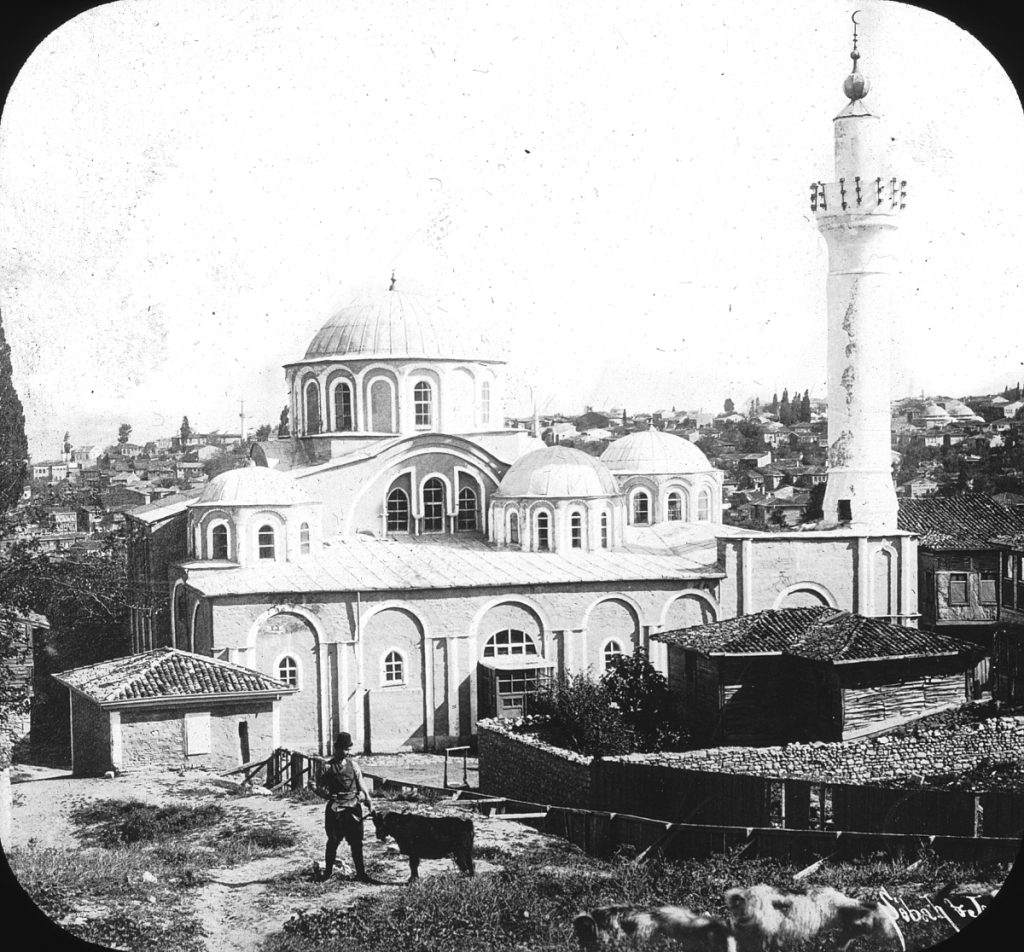

The recent change in the use and legal status of Hagia Sophia implemented by a ruling of the Turkish Council of State, privileging fifteenth-century Ottoman endowment law over that of the current state, and decreed by the Turkish President caused national and international pandemonium. Almost 1,500 years old, Hagia Sophia was built in the sixth century, probably on the site of a pagan temple and earlier churches which were destroyed by riots and served as a major Orthodox cathedral and the seat of the Patriarchate for more than nine centuries. After being taken by the Ottomans in 1453, it was converted into a major mosque and maintained that status almost six centuries until 1934. Within the legal system of the newly founded secular state of the Republic of Turkey, the successor to the Ottoman Empire, Hagia Sophia’s official status was changed again with the aim of establishing a museum. As much as it might have been colored by political motivations, the attempt to embrace Byzantine heritage overtly, even, as shown by Edhem Eldem, to project a proper museum of Byzantine art in Hagia Sophia where Byzantine collections of the former imperial museum could have been displayed, was a radical move on the part of the new state in that historical juncture. It also was much more in accord with our current understanding of cultural heritage vis-à-vis the recent decision to restore the mosque function to a cultural heritage site.

Before and after the conversion decision, outcries were voiced regarding its decoration as well as the future protection and lack of accessibility of the edifice, perhaps with the exception of Sunni men. The dust raised by the decision was intensified with the July 24 opening ceremony. There was disagreement even about the object of dispute: the “museum space” of the secular republic, or the Orthodox cathedral that Hagia Sophia ceased to be 567 years ago. Nevertheless, the American and Greek Orthodox Churches, in a symmetrical fashion, declared July 24 a day of mourning, overlooking the fact that what was being converted was already a heritage site and not a cathedral.

Since then, Hagia Sophia, which was primarily a tourist destination as part of the UNESCO world heritage site “Historic Areas of Istanbul” located on the edge of Europe and originally belonging to the much-overlooked Byzantine legacy, became a global cause célèbre. The building complex actually never functioned as a proper museum. Yet, with an interesting turn of events it began to be viewed solely in the light of its presumed former functions and froze as either cathedral, mosque, or museum in the minds of the global public.

Amid the polarizations caused by the controversy in Turkey, particularly between “secularists” and “Islamists,” Hagia Sophia’s conversion into a “museum” is attributed exclusively to Turkish republican authorities, overlooking its gradual transformation into a “monument” in the Ottoman era. Robert Nelson had already shown us the creation and reception of Hagia Sophia as a “modern monument” alongside an emerging interest in Byzantine past in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Similarly, Edhem Eldem wrote about its transformation by the Ottomans into a site whose primary purpose was to be visited by foreign travelers.

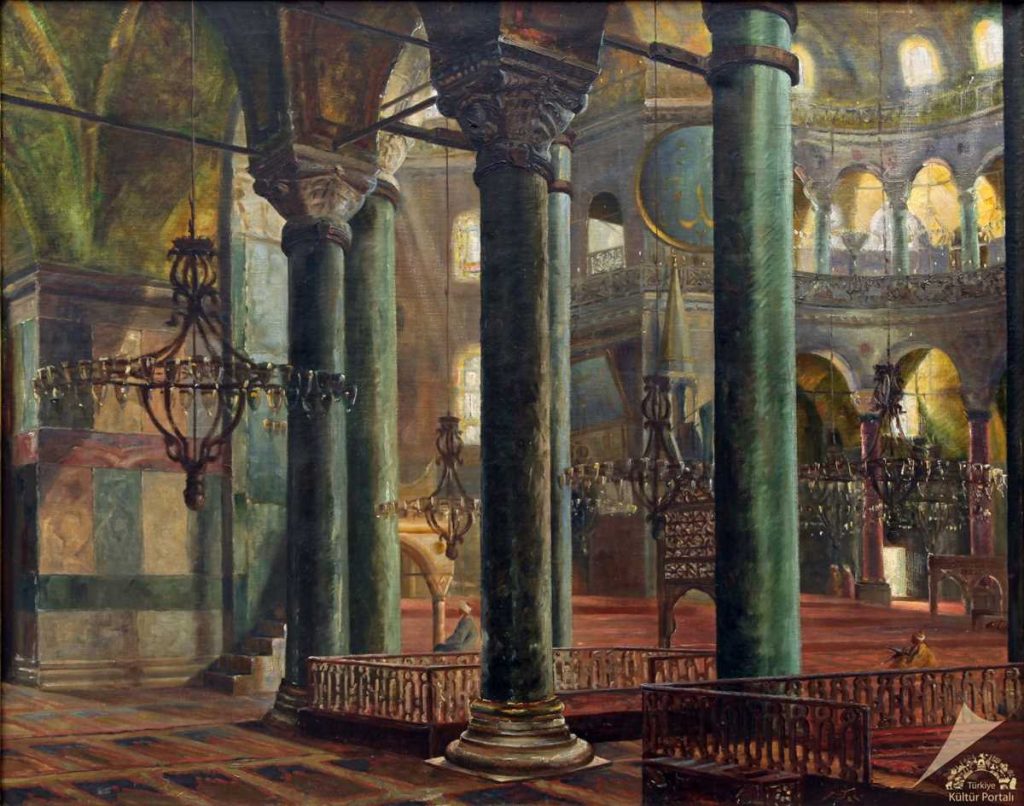

Along those lines, I too would argue that, apart from its life as a major religious and civic complex with a stupendous library and schools, a parallel process of “monumentalization” and “aestheticization” of it as an historical and artistic artifact was already taking place in the nineteenth century, at which time it began to be seen as an example of asar-ı atika and asar-ı nefise, the developing concepts of “ancient and artistic works.” If Gaspare Fossati’s extensive depictions of Hagia Sophia occasioned by his employment by the Ottoman court for repairs in the 1840s alongside Wilhelm Salzenberg’s work on its decoration were turning points in Hagia Sophia’s life as a “monument,” recording Byzantine art and architecture would be taken up by Ottoman intelligentsia, too. Celal Esad wrote about Hagia Sophia as a Byzantine edifice in detail first in Ottoman then in French. Mehmed Ziya, on the other hand, published a monograph on Kariye mosque with extensive descriptions of its Byzantine imagery, which were discovered in 1876, left exposed and documented by the Imperial Museum, the images of which were used also in Abdulhamid II’s gift albums to Britain and the US.

In the nineteenth century, Hagia Sophia alongside other mosques and the Ottoman Imperial Museum, the small collection of particularly Greco-Roman and Byzantine antiquities amassed in another spoliated Byzantine church, Hagia Irene, and the former imperial palace, Topkapı, had already become principal tourist destinations. By the 1890s a specific section was already in place for foreign visitors which was furnished with sofas and damask chairs and even a fee was presumably being charged. The Ottoman State Archives are full of petitions for permission to visit, paint, photograph and survey Hagia Sophia not only by foreigners but also Ottoman Muslims.

The recent conversion of Hagia Sophia back into a mosque, alongside all the other recent assaults on “cultural heritage” throughout the world, shows us that the concepts of “monument” and “cultural heritage” are now in crisis. The value of Hagia Sophia as a piece of global common heritage, a UNESCO world heritage site, beyond regional and national divides is being contested. Recent critical literature argues that the massive bureaucratic machine of UNESCO, rather than uniting, is actually consolidating national boundaries and is dominated by a few hegemonic centers (see for instance the work of Lynn Meskell). In the face of this, what can be done? Perhaps we may start from how we write our histories. Instead of exclusionary narratives that focus on single periods, cultures, and identities at the expense of others that end up building boundaries along religious and national divides, we may insist on nuanced and pluralistic histories that disclose continuities and connections between seemingly different cultures. When we start to see Hagia Sophia holistically with all its phases that connect different periods, cultures, functions, and meanings – Byzantine as much as Ottoman, mosque as much church, secular as much sacred – we may be ready for new transnational values including a genuine and more convincing concept of “cultural heritage.”

Mosque, Museum, or Church?

Helen Frowe and Derek Matravers

Insofar as we generally grant states ownership claims over immovable objects within their territory, there is reason to think that Turkey has at least some claim to decide the function of Hagia Sophia. After all, if we doubt that Turkey has such claims over its territory, then the status of Hagia Sophia should not be our most pressing concern. Legal claims of this sort plausibly have at least some moral force. But they are not the only thing with moral force. Here, we canvass some of the other moral considerations that bear on how Hagia Sophia ought to be used.

The judgement of the Turkish court that Hagia Sophia must be turned back into a mosque is grounded in the fact that Mehmed II’s settlement stipulated that it is to be so used. The court held that Atatürk was not entitled to override these wishes. We might agree that, ordinarily, such a stipulation by a previous owner has both legal and moral force. But it is hard to see how such an appeal can succeed in this case. If it was wrong for Atatürk to turn the mosque into a museum because this contradicted Mehmed’s wishes, then it was surely wrong for Mehmed to turn the church into a mosque in contradiction of the wishes of the church’s previous owners. The fact that Mehmed obtained control of Hagia Sophia through conquest, and Atatürk via internal political reforms, does not seem to give Mehmed greater moral claim to override the previous owner’s wishes. None of this is to say that Hagia Sophia should not be used as a mosque. It is merely to say that, at least morally speaking, the court’s basis for its ruling looks unpersuasive.

We granted, at the outset, that Turkey has at least some claim to decide the function of Hagia Sophia. We might think that the Greek Orthodox community also have such a claim, given that (a) they are the originator culture (or at least one of the originator cultures, given that the Ottomans extended the building), and (b) their rights were violated by the Ottoman conquest. Their claim is stronger if both (a) and (b) are true. But we doubt that they have a claim only if both are true. For example, a weaker version of (b) might suffice – namely, that the Greek Orthodox community did not voluntarily sell or gift the Hagia Sophia to the Ottomans. Even if originator cultures can come to lose controlling rights over artefacts by selling those artefacts under fair conditions, it seems unlikely that the same is true when artefacts are taken by conquest.

We can be largely neutral here on how we ought to treat ownership rights when the possession of a good is the result of historical conquest, bearing in mind the extent to which modern-day states are the result of unjust expansions and aggressions. Endorsing the modest and relatively uncontroversial claim that conquest is not a morally decisive mechanism for the allocation of moral rights suffices to support the Greek Orthodox claim to some say over Hagia Sophia’s fate. There are all sorts of reasons why it is often impossible or undesirable to return unjustly acquired goods to their original owners. Some of these difficulties are particularly acute when it comes to territories and immovable objects located within them. But it is compatible with this that, sometimes, there are multiple moral claims to control over goods taken by conquest. Such claims need not to amount to a right to outright ownership, or an artefact’s return, or the ceding of the relevant land. But the fact that a claim is not decisive in this way does not entail that it is irrelevant. On the contrary: it can still have moral weight, and make demands upon us. For example, it’s plausible that indigenous peoples lack a right to demand the mass exodus of inhabitants descended from even violent foreign settlers. But this does not mean that indigenous people lack claims regarding the use of the land altogether. Moreover, our suggestion is that the Greek Orthodox claim is partly grounded in its status as Hagia Sophia’s originator culture. Since land has no originator culture, our argument does not commit us to a particular resolution of claims about territorial disputes.

The foregoing gives us some reason to think that members of the Greek Orthodox Church have a claim to a say over the use of Hagia Sophia. And let’s grant that the Turkish government has some claim as well. Assume that the Greek Orthodox Church’s first preference is for Hagia Sophia to be a church, that their second preference is that it be a museum, and that they do not want it to be a mosque. And assume that the Turkish government’s first preference is for Hagia Sophia to be a mosque, that their second preference is for it to be a museum, and that they do not want it to be a church. We cannot satisfy both claimants’ first preference. But we can satisfy both claimants’ second preference. Given these assumptions, keeping Hagia Sophia as a museum best recognizes the moral claims at stake.

Appropriating Language, Appropriating the Great Church

Selin Ünlüönen

What can we say about the Hagia Sophia Holy Grand Mosque, more than a year after its conversion from a museum? The pageantry of the first Friday prayer in July 2020 (livestreamed on Facebook) has lost its place in the spotlight to other news and newer crises. Academic calendars run on their own, cooler time, so it was only in October of 2020 that the Turkish Directorate of Religious Affairs, under whose purview Hagia Sophia now lies, organized a splendidly funded academic symposium dedicated to the building, also livestreamed, on YouTube. On the symposium program, the sole presentation about Hagia Sophia’s mosaics was on the iconoclastic debate, delivered by a Turkish academic, Bilal Baş, who is not an art historian. According to Baş, the Byzantine iconoclasts of the ninth century and those covering up the mosaics in 2020 are on the same side of a theological debate. The point, made with all of the subtlety of a sledgehammer, was that Byzantine scholars themselves did not care for any figurative mosaics for most of the church’s life, so why should you.

A thoughtfully worded petition against the museum’s conversion in English that circulated prior to the official conversion made an important distinction between use and stewardship. A building does not have to be a museum for it to be well taken care of as cultural heritage. This distinction is important in light of some of the criticism against Erdoğan’s decision. A common thread of backlash either questions the legitimacy of Turkey’s sovereignty (not of Erdoğan, but of the people of Turkey) over the country’s own cultural heritage, or argues that becoming a place for Muslim worship is completely unsuitable for the building. It is not difficult to see the imperialist and Islamophobic undertones of these arguments. There are numerous churches in Europe that were formerly mosques. And it is difficult to hold that hearing Christian choral music in San Miniato al Monte detracts anything for the non-believer from the transcendental pleasure of being in the building.

If Baş reads Byzantine history selectively and only to find bits of what will agree with his foregone conclusion, others bulldoze over any sort of historicity in claiming that Hagia Sophia belongs to the world before it belongs to its immediate stewards, stakeholders, and communities. In the first case, a bad historicism renders the art completely invisible. (If the Turkish scholar had a slideshow of the mosaics he discussed, it did not appear on Youtube). In the second case, a misconceived and antagonistically worded concern for the monument erases the claims over the fate of Hagia Sophia of the Greek Orthodox community, Istanbulites, and people of Turkey. Hagia Sophia is ill-served by both attitudes.

And of course, wording of criticism matters when we consider the history of a monument. The thing that stays with me the most vividly is Erdoğan’s speech defending the conversion of Hagia Sophia into a mosque. His speech was televised live on every single TV channel. Atatürk loomed large. Hagia Sophia the mosque had been turned into a museum following the founding of the young Turkish Republic. The monument’s status as a museum was braided into the new state identity along with the rhetoric of nationhood, progress, and self-sufficiency. In his speech, Erdoğan now used the same rhetoric against those very ideals of the secular republic. Referring to the secular crowds opposing the museum’s conversion, Erdoğan said, “They cannot stand that we have become modernized and have turned into a confident, self-sufficient country. Those who were against building the third bridge in Istanbul are also against this.” Erdoğan is certainly not alone in pillaging the language of the opposition to silence that very opposition.1 The history and historicity of Hagia Sophia has salience for this reason, too: if we lose something when Hagia Sophia is no longer a museum, we also lose something when our language of articulating its history is rendered empty of any meaning.

Where does that leave Hagia Sophia? I am afraid, obscured as a work of art, and unable to embrace this polarized public with its graceful dome. If the discussions around Hagia Sophia’s conversion shows us anything, it is that as citizens and students of humanities, our job is to look, think, and understand. Art belongs not to those who instrumentalize culture and weaponize history, but to those who are open to be shaped by it.

1 If this feels foreign, you may want to recall the chilling moment when Mike Pence—who was complicit in spreading destructive misinformation and whose political situation long benefited from blatant lies—said to Kamala Harris, “You are entitled to your own opinions, but you are not entitled to your own facts.” You can buy that sentence on a sweatshirt with Pence’s face plastered over it.

Why Not Let It Be a Mosque?

David Killoren

I care about Turkey and its affairs for many reasons, including the fact that my future is in Turkey. In September of 2022, I will start as an Assistant Professor of Philosophy at Koç University in Istanbul. But I’m not a Turkish citizen. In Turkish society, I’m an outsider, albeit a keenly interested one. Hagia Sophia’s fate is not for me to decide. That said, as a philosopher, I can consider reasons and arguments. And I have yet to see a fully persuasive argument for the view that Hagia Sophia should be a museum rather than a mosque.

Some arguments for that view appeal to the fact that Hagia Sophia is important to and meaningful for all of humanity, not just Muslims. I think this is what UNESCO is getting at when it refers to the “universal nature of [Hagia Sophia’s] heritage” in its statement opposing the change. But I do not see how this consideration supports the view that Hagia Sophia should be a museum rather than a mosque.

Perhaps the thought is that non-Muslims are less able to appreciate Hagia Sophia if it is a mosque. But why would that be so? Consider the Notre-Dame cathedral in Paris. It is not currently set up as a museum, and one doubts whether it ever will be. Mass is held in the cathedral every day. But few believe that this detracts from visitors’ ability to appreciate it, even if those visitors are not themselves Christians.

In fact, if Notre-Dame were converted into a museum, this might make it harder to appreciate it as the kind of thing that it is. Imagine visiting an old bar where great musicians used to play—only to find that it has been turned into a museum. Then I think it might be harder, not easier, to appreciate it as the kind of thing that it is, or was.

I don’t mean to suggest that Notre-Dame must always remain what it is today. At this moment—late Nov. 2021—there is hubbub over a reported renovation proposal to transform Notre-Dame into what conservative critics derisively call an “experimental showroom,” and it has been claimed that the proposal would turn the cathedral into a museum. I have no principled objection to these sorts of plans. I do not believe that there’s anything inherently wrong with repurposing the monuments we’ve collectively inherited, even when doing so is not just creative but also destructive.

But it seems to me that if Notre-Dame in its current form as a Christian cathedral has universal significance, as many believe, this significance must be based in its nature as an expression of a particular religious culture that existed at a particular place and time. Given this, I don’t see how its status as a still-functioning church would impede visitors’ ability to appreciate its universal meaning. And if this is true of Notre-Dame, I think it’s also true of Hagia Sophia.

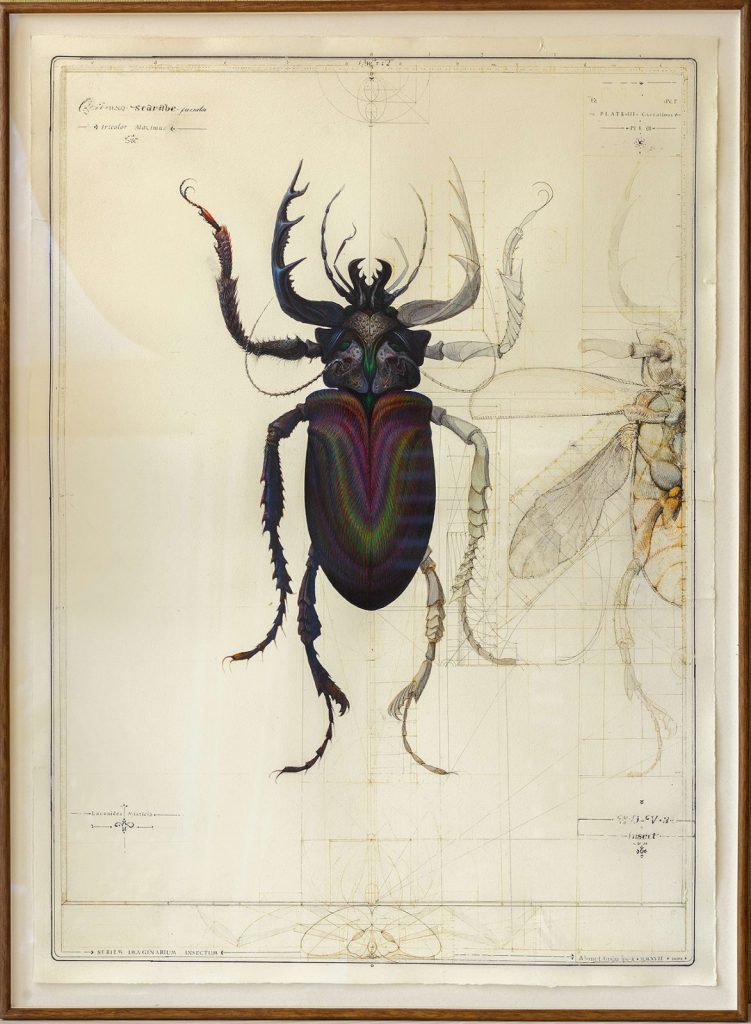

Of course, Hagia Sophia differs from Notre-Dame in many important respects. It’s easy to say what kind of thing Notre-Dame is—it’s a Christian church, and has always been one—whereas Hagia Sophia has undergone numerous transformations, each of which has had distinct cultural, political, and religious meaning. I think Hagia Sophia’s capacity for transformation is in its nature, like an insect with a wildly varied lifecycle.

Given this, it seems to me that appreciating Hagia Sophia as the kind of thing that it is requires attention to and even acceptance of its whole life, including its present stage as a mosque—even if this means that Hagia Sophia in its present form might be less easily accessible to visitors who want to appreciate it. So, I think I differ with some, such as the NYT Editorial Board around the time of the conversion, who have seemed very worried that mosque status will interfere with Hagia Sophia’s accessibility to the public. I think we make an aesthetic error, and perhaps also a moral error, if we fail to accept that some beautiful and awe-inspiring things aren’t always on full display.

There are at least three separate groups who want a say in what’s done with Hagia Sophia: Christians, Muslims, and secularists. Some contend that museum status would be a neutral middle ground between these factions and for that reason is preferable. But I think it can be argued that making it into a museum again would be to give a win to one faction—namely, secularists—at the expense of other factions. In this situation, there might not be any way to find a genuinely neutral use of Hagia Sophia. If that is so, it might be reasonable to simply let Hagia Sophia be used in whatever way the Turkish people want it to be used. After all, Hagia Sophia is centrally located in Turkey’s largest city—Istanbul. And although reliable polling on this matter seems a bit scarce, there are some opinion polls that indicate that a majority of Turkish people want Hagia Sophia to be a mosque.

The Crusoes of this World

Ege Yumusak

The most influential Middle Eastern scholar of the last century was a bit of a standpoint epistemologist in his own right. In his ruminations on exile, Edward Said wrote about a privileged standpoint that any intellectual could claim for themselves:

“An intellectual is like a shipwrecked person who learns to live in a certain sense with the land, not on it, not like Robinson Crusoe, whose goal is to colonize his little island, but more like Marco Polo, whose sense of the marvelous never fails him, and who is always a traveler, a provisional guest, not a freeloader, conqueror, or raider.”

He found much to affirm in the attitudes of the displaced: the ability to marvel at what we have, to appraise the contingency in what’s taken place, and to escape the logic of the conventional. From where I stand, though, Said’s veneration of the exilic perspective mirrors two ideological positions that belong to the Crusoes of this world:

- The Turkish intellectual’s imaginary of having a privileged standpoint between East and West, which betrays a lack of reckoning with an imperial and revolutionary past, and its lived violent and repressive reality in the present;

- The philosopher’s insistence on abstracting away history and universalizing hegemonic value systems, resulting in an inability to grapple with the contestation of modernity and its normative regime in the Islamic world.

What underlies these claims to epistemic privilege of the Turkish intellectual, the philosopher, and the Saidian scholar in exile is an ask to be spared from criticism. They maintain that their critique is authoritative precisely because it is out-of-place and somewhat false.

Nearly two decades after his death, the jury is out on whether Said’s oeuvre can be characterized with the audacity that once seemed true to ascribe to him. It increasingly seems that there is no ‘undercommons’ to be dug under the quadrangles of undemocratic institutions funded by the capitalist establishment (as in the case of private universities) or presided over by criminal “public” officials (as in the case of governing boards of public universities). Intellectuals who claim some epistemic privilege are merely asking for undue deference.

That’s why I will not talk about the rights and obligations of the state of Turkey over Hagia Sofia or other philosophical questions that are readily available to us. Instead, I’ll take us back to 2019 to uncover a more urgent epistemic project.

On March 15, 2019, two mass shootings in Christchurch, New Zealand took place during Friday prayer and killed 51 people. We know that the perpetrator visited Turkey, and was captivated by the history of the Ottoman Empire. He wrote in his lengthy manifesto:

“If you attempt to live in European lands, anywhere west of the Bosphorus, we will kill you and drive you roaches from our lands. We are coming for Constantinople and we will destroy every mosque and minaret in the city. The Hagia Sophia will be free of minarets, and Constantinople will be rightfully Christian-owned once more.”

As the manifesto circulated, the demands for the conversion of Hagia Sophia grew louder. Erdogan was concerned that a symbolic conversion would threaten mosques all over the Christian world. “Let’s not be fooled by these tricks. This is a provocation,” he implored.

By March 24, it was clear that Erdogan’s resistance could have consequences for the monumental mayoral election. So, he made a commitment to change Hagia Sophia’s name and make entrance free. In the following weeks, he would show videos of the Christchurch shootings and reiterate his new position to make up lost ground. Still, Erdogan’s AKP lost the mayoral election to Ekrem Imamoglu.

A year later, on July 24, 2020, Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque opened its doors to worshippers. News articles reported on a range of political emotions. Pope Francis was “very saddened”; the culture minister of Greece regarded the conversion “an open provocation to the entire civilized world”. Western outlets like BBC, Reuters, CNN, and NY Times described the crowds with evocative Islamic imagery, including videos of adhan. Many intellectuals from Turkey (and darlings of the West) matched Western media’s alarmism. The Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk told the BBC, “To convert [Hagia Sophia] back to a mosque is to say to the rest of the world unfortunately we are not secular anymore.”

None of the Western outlets referenced March 2019, when a white supremacist massacre put Hagia Sophia in the center of Turkey’s political stage during a critical election.

Erdogan catered varying remarks for his varying audiences. In Arabic, he said Hagia Sophia’s conversion foreshadows the liberation of al-Aqsa mosque. The Turkish and English speeches omitted this remark and instead made references to the conversion of the Grand Mosque of Cordoba to provide justification for the conversion.

Ekrem Imamoglu, Istanbul’s new mayor who is a member of the secularist party, but who stays at a distance from its bourgeois aristocracy, made the link. He directed Erdogan a simple question, “Will anything happen to these mosques where tens of thousands of Muslims, my expat brothers, pray?” He did not contest the conversion but voiced worries about the rising unemployment and the reliance of Turkey’s economy on tourism. With the conversion, Turkey has forgone $72 million in ticket sales, once providing greater income than the annual toll collected from Istanbul’s bridges.

Hagia Sophia’s conversion did not dominate the news cycle for long. The subsequent decision for the conversion of the Chora Church did not receive international attention.

Taking a wider-angle on world-historical events makes this much clear: Hagia Sophia has been a site of contestation in a world of empire and it remains a site of contestation after empire. We still owe the people who want to appreciate its beauty and engage in practices of transcendence inside its walls an internationalist vision for liberation. To do that, we need to ask what kind of epistemic community would be best suited to shirk off the nightmare delivered to us by the Crusoes of this world and articulate a freedom dream.

Edited by David Killoren and Alex King