What follows is a guest post by Wesley D. Cray (Texas Christian University).

At the beginning of this semester—Fall 2021—I announced my resignation from higher education. I’d be leaving my tenured position at Texas Christian University and taking up the position of Director of LGBTQIA+ Programming at the largest provider of virtual intensive outpatient therapy in the United States, where roughly 70% of our clients are members of LGBTQIA+ communities. Since then, I’ve been very careful to clarify whenever it comes up that I’m not leaving academia, but just the university system. My research communities, including the American Society for Aesthetics, are too dear to my heart for me to not remain connected as much as is manageable. Ideally, that connection will include continuing to attend various conferences, which I’ve always found—on the whole—invigorating and affirming, on both professional and personal levels.

It’s incredibly disheartening, then, to hear that apathetic attitudes toward pronoun usage and basic respect toward persons and their gender identities still constitute a noteworthy presence in our communities. Even if such attitudes are not the dominant attitudes, their effects can be felt, and those effects matter—whether they impact a senior, long-time member of the profession or a graduate student who had their first in-person conference experience tarnished by a pattern of disrespect.

I’m not writing this piece in the hope of convincing and converting reactionaries who advocate for transphobic policies on the basis of trans-exclusionary gender ideology. It would take more than the space I have available here to disabuse such advocates of the fallacies, junk science, and faux-feminist politics at the heart of such views. Instead, the audience I hope to speak to includes those who want to be—maybe even already consider themselves to be—genuine allies of the broad and inclusive transgender, non-binary, and gender-nonconforming communities.

In this spirit, I’ll provide the following: a brief discussion of some harms of misgendering; some suggestions for relevant best practices we could adopt moving forward, both institutionally and individually; and, finally, a small handful for suggestions for further resources pertinent to this topic. My aim is to encourage well-meaning members of our research communities to make an active effort to create a more inclusive space for colleagues inhabiting the full spectrum of gender identities.

Some Harms of Misgendering

If you were to inadvertently misgender a cisgender person—that is, use a typically masculine-coded pronoun (‘he’, ‘him’, ‘his’) for a cisgender woman or a typically feminine-coded pronoun (‘she’, ‘her’, ‘hers’) for a cisgender man—you would likely take yourself to have made a mistake. Similarly, I imagine that you would clearly understand why the recipient of the misgendering act might take offense, ranging from minor to major depending on the context. If the error continues to the point of becoming habitual, the offense will almost certainly—and understandably—grow.

Trans persons deserve the same level of respect as cisgender persons. But oftentimes, the reactions we receive when it is pointed out (by us or by others) that someone has misgendered us differ from that which you likely imagined in the previous scenario. It is not uncommon for the perpetrator of the misgendering act to assume a defensive stance, commenting that “it’s just so hard to remember,” or that they’re “still learning” or “practicing” and that we “need to remember that people are going to make mistakes.” Perhaps even falling back on the claim that they “had no way of knowing.” Sometimes the defensive stance is accompanied by a deep sigh, awkward laughter, or even an eye roll. These reactions send a clear message: whether the perpetrator realizes it or not, they do not afford trans persons the same level of respect as cisgender persons. This differential helps constitute and sustain transphobic environments, institutions, and practices.

Few should have trouble imagining how the persistent misgendering of a cisgender person—whether intentional or due to negligence—could take a mental and emotional toll on that person. The harmful effects on trans persons are predictably more substantial, insofar as misgendering can exacerbate gender dysphoria: a significant distress or discomfort due to felt incongruence between gender expression (and the way such expression is socially received) and gender identity. Such dysphoria can prove lethal: roughly one-half of adolescents and young adults diagnosed with gender dysphoria report having experienced suicidal ideation, and roughly one-quarter have attempted suicide (García-Vega, et al 2018; see also Day, et al 2019).

The official position of the American Medical Association is that someone suffering from gender dysphoria ought to receive treatment in part through allowing and encouraging that their outward gender expression be brought into congruence with their internal gender identity. The adoption and uptake of gender-affirming pronouns is one way of allowing and encouraging this congruence. On the other hand, the lack of such uptake actively frustrates congruence, thereby running the risk of perpetuating or exacerbating potentially lethal gender dysphoria.

Those who have never experienced debilitating gender dysphoria might have trouble grasping how the incongruence I am describing can feel so devastating. Ultimately, though, you don’t need to see how it can in order to see that it can. And the evidence that gender dysphoria is a very serious matter comes, quite simply, from the sincere testimony of trans persons, both anecdotally and as collected through systematic medical study. These studies are useful for driving the point home, but ideally, the anecdata would be sufficient: if someone tells you that something you are doing hurts, you have good reason to stop doing it, even if you don’t understand why or how it hurts.

A final thought: as academics, I’d like to think that we have a commitment to the truth. An act of misgendering amounts to an epistemic error. An attitude of permissiveness toward misgendering is an attitude of permissiveness toward serious errors. Citing how ”difficult” correct pronoun usage is amounts to intellectual laziness, especially for academics who spend much of their time working through significantly more difficult practical and conceptual issues. So, in this spirit, I offer a plea: both individually and collectively and for the sake of the members of our communities, let’s do better.

Suggestions for Best Practices

Here is a short, non-exhaustive list of suggestions for best practices at the institutional level.

- Pronoun badges ought to be made available at conferences. These badges should offer a range of pronoun options (including mixed sets, such as “she/they”) and be large enough to be read at a distance. To aid in this, color-coding might prove especially effective. Cisgender persons ought strongly consider participating in this practice as well, so that it becomes a standard practice rather than merely a “trans thing.” (If you are worried that doing so will give the impression that you are merely “virtue signaling,” please consider that as practices such as these receive wider uptake, such impressions will fade.)

- Conference participants ought to be able to opt for the inclusion of their pronouns on conference programs. The same recommendation applies to publications in journals, and the previous note regarding cisgender participation continues to apply here, as well.

- During conference presentations, it ought to be the chair’s responsibility, as chair, to use the proper pronouns for all session participants. The chair should also check with participants prior to the session regarding their preferences for how to handle potential misgendering during the session itself, and then proceed to act accordingly.

- Habitual misgendering ought to be a censurable offense, at an institutional level.

Here is a short, non-exhaustive list of suggestions for best practices at the personal level.

- If you accidentally misgender someone: correct yourself, apologize, and move on. Do not subject the recipient to an extended display of your guilt or an explanation of “how bad you feel,” “how hard it is,” or “how hard you’re trying.” This is often incredibly uncomfortable and only serves to further solidify any harm done.

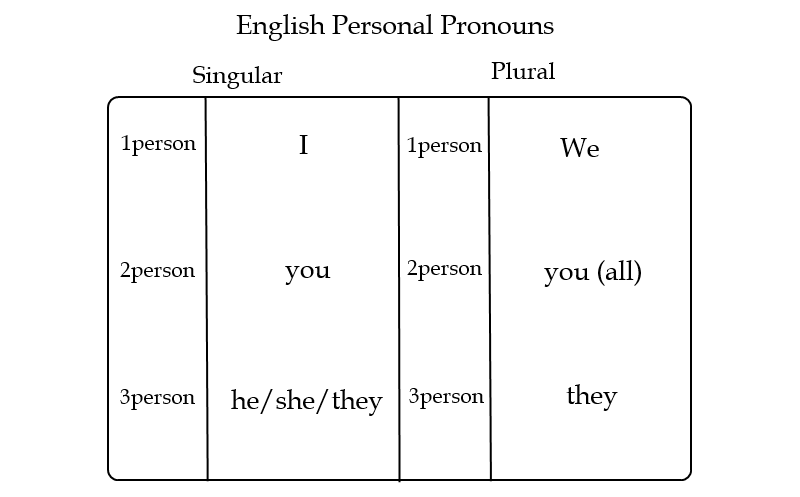

- Be mindful of the fact that someone’s outward appearance is not a reliable guide to their gender or pronouns. If you are unsure of someone’s gender, default to using their name or the gender-neutral, singular ‘they’. If you are somehow convinced that ‘they’ is invariably plural, please simply do a brief study of the history of the usage of the word.

- Observe proper pronoun practices no matter who is around. This will help you build better linguistic habits, and also contribute to building and maintaining a climate in which persons are comfortable being public about their identities and pronouns.

- Regardless of your gender identity, please consider including your pronouns in your email signature and other such correspondence. You might also consider getting into the habit of offering your pronouns along with your name when you’re first introduced to someone.

- Work toward conceiving of this issue as one of building an atmosphere of respect, rather than thinking of it solely as a superficial issue of linguistic preference.

- Listen to your trans friends and colleagues. Do not use them as your personal libraries on these and related issues, but when they do share, actively listen to them. If you don’t have any trans friends or colleagues (that you know of), take time to actively consider why that might be.

Some Resources

Next, here are some resources that I am confident will prove helpful to anyone who is hoping to make a good-faith effort toward better understanding these issues and implementing the above practices.

At the academic level, the following journal articles and book chapters are fantastically informative and helpful.

- Dembroff, Robin and Wodak, Daniel. Forthcoming. “How Much Gender is Too Much Gender?” In Justin Khoo and Rachel Katharine Sterken (eds.), Routledge Handbook of Social and Political Philosophy of Language. Routledge.

- Dembroff, Robin and Wodak, Daniel. 2018. “He/She/They/Ze.” Ergo 5.

- Hernandez, E.M. Forthcoming. “Gender Affirmation and Loving Attention.” Hypatia.

- McKinnon, Rachel. 2017. “Allies Behaving Badly: Gaslighting as Epistemic Injustice.” In Ian James Kidd, José Medina, Gaile Pohlhaus, Jr. (eds.), Routledge Handbook of Epistemic Injustice. Routledge.

For more a casual trade book, I recommend:

- Baron, Dennis. 2020. What’s Your Pronoun?: Beyond He and She. Liveright.

For those who like their information in comics form:

- Bongiovanni, Archie and Jimerson, Tristan. 2018. A Quick & Easy Guide to They/Them Pronouns. Limerence Press.

And finally, a quite wonderful online resource:

- MyPronouns.org: Resources on Personal Pronouns

Please, Do Your Part

Just as I didn’t write this piece to convince transphobic ideologues, I also didn’t write it with the intention of pointing fingers. We all have work to do to make our communities—including our research communities—safer and more inclusive.

What I’m asking is for you to do your part, and to do it mindfully and in good faith. I see up close the effects of persistent misgendering on adolescents and young adults regularly, and that sight is heart-breaking. My heart breaks, too, to know that some among my friends and colleagues in the ASA (and other corners of academia) are similarly affected. With 2021 being the deadliest year on record for trans persons (Parks 2021) and seeing a record amount of anti-LGBTQIA+ legislation in the U.S. (Ronan 2021), let’s please commit to making our communities part of the solution rather than negligently perpetuating the problems.

References

- Parks, Casey. 2021. “2021 is the Deadliest Year on Record for Transgender and Nonbinary People,” Washington Post. November 10th.

- American Medical Association. “Advocating for the LGBTQ Community.”

- Day, Derek; Saunders, John; and Matorin, Anu. 2019. “Gender Dysphoria and Suicidal Ideation: Clinical Observations from a Psychiatric Emergency Service.” Cureus 11(11).

- García-Vega, Elena; Camero, Aida; Fernández Mária; and Villaverde, Ana. 2018. “Suicidal Ideation and Suicide Attempts in Persons with Gender Dysphoria,” Psicothema. 30(3): 283-288.

- Ronan, Wyatt. 2021. “2021 Officially Becomes Worst Year in Recent History for LGBTQ State Legislative Attacks as Unprecedented Number of States Enact Record-Shattering Number of Anti-LGBTQ Measures Into Law,” Human Rights Campaign. May 21st.

Notes on the Contributor

Wesley D. Cray (she/they) is Associate Professor of Philosophy at Texas Christian University, at least for a few more days. She is currently Secretary of the Rocky Mountain Division of the American Society for Aesthetics. Outside of academia, she works with LGBTQIA+ adolescents and young adults in clinical contexts, as well as offering practices such as Queer Mindfulness and Trans Yoga. You can follow her work at www.wesleycray.com.

Edited by Matt Strohl