What follows is a guest post by Tea Lobo. It is based on her video essay “What Makes Cities Beautiful?”

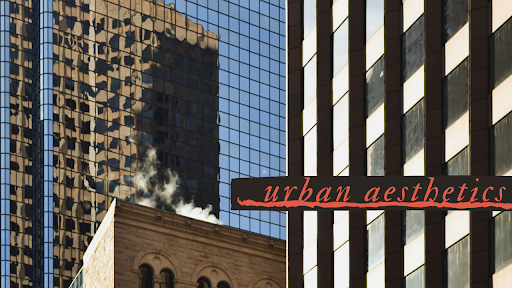

In everyday life we often experience cities as beautiful: we revel in the dizzying heights of Chicago, or in the way light reflects on the waters and windows of Utrecht, or perhaps the hustle and bustle of Jiufen and the feeling of having lost track of what is up and what is down. However, the city is only a marginal topic in aesthetics, the branch of philosophy dealing with beauty. What possible reasons are there for this disconnect between the interests of ordinary people and the activities of professional philosophers? What can be philosophically said about urban aesthetics?

The field most closely related to urban aesthetics is architecture. But architecture was considered to be at the bottom of the hierarchy of the arts in the history of philosophy. Allegory of the Arts, a painting by Pompeo Girolamo Batoni from 1740 depicts young girls as personifications of the different art forms. Painting is depicted in the center, perhaps not surprisingly given the medium, closely flanked by Poetry. Sculpture is sitting on the floor and adoringly looking up at both, while Music and Architecture are in the background. Architecture is the furthest away in the background shadows, and not as worthy of the viewer’s attention as the other Arts.

The reason for Architecture’s lower standing in the hierarchy of the arts is its practical use: even the most aesthetically breathtaking buildings normally have a practical, everyday purpose in addition to their artistic values. According to Kant and Hegel, art as such has intrinsic value. This means that art is an end unto itself, and therefore cannot be a mere object of practical, everyday use. However, architectural works are built to serve functions as educational facilities, as governmental buildings, or as residences or houses of worship, and these practical uses sully their aesthetic value in the eyes of classical Western philosophy of art.

Because we value art for its own sake, it is normal to visit museums with the express purpose of contemplating paintings. But we hardly ever contemplate cities in the same way. This activity is usually reserved for only certain people, those who lack a “normal” relationship to the city. The most obvious case is tourists, who have the leisure to contemplate the skyline of a city. However, for most people the urban landscape registers as a backdrop to their everyday activities, as when one is running to catch a bus and fragments of the city vista flash at the edge of one’s vision.

Because painting was considered superior to architecture, the beauty of cities has historically been evaluated according to the standards of paintings. For instance, Aristotle said in the Metaphysics, “The chief forms of beauty are order and symmetry and definiteness.” On this view, forms are judged as beautiful if they are unambiguous and clearly decipherable, and this view paved the way for representationalist painting which valued clear, symmetrical, easily identifiable forms.

In the Renaissance, when ancient thinkers were being rediscovered in Europe, ideal cities were being built using strict geometrical standards—precisely because of Aristotle’s views on beauty. The Renaissance was also the heyday of linear perspective in painting. And so cities were designed, similarly, to look breathtaking from a particular angle. The beholder was meant to have a very specific view of the city—say, of and from a piazza. Viewed from this angle, the city would display nice, geometric lines that would reveal its true beauty.

This celebration of geometry had its climax in Modernism. The Swiss architect Le Corbusier, for example, designed ideal cities in just this manner. His highly gridded La Ville Radieuse was designed so that all apartments were exposed to equal doses of sunshine due to the city’s strict geometrical layout.

Contrary to the aesthetic of perfectly straight lines, there was a different aesthetic. As early as the nineteenth century, people were expressing reservations about this geometric ideal. in his book The Art of Building Cities: City Building According to Its Artistic Fundamentals, Camillo Sitte pleaded for a more street-eye, observer’s approach to urban aesthetics, drawing attention to the fact that nobody experiences a city by looking at a map. Later, in the 1940s, Walter Benjamin called architecture a truly democratic art because it is available to all. We don’t have to pay entrance to a museum to experience the aesthetics of a city; rather, we experience it in the hustle and bustle of everyday life. He claimed that we experience architecture in a state of distraction—for instance, while running to catch a bus.

It is primarily tourists who contemplate the city like a painting. The rest of us experience it on the go, or kinaesthetically. Kinesis is Greek for ‘movement’ and aisthesis is ‘perception’. So to experience a city kinaesthetically means to experience it by stitching together glimpses caught while walking, driving, biking, or even roller-skating. It is especially when we are in motion, on the go, that the city becomes an aesthetic object for us. And it is no accident that the character of the flâneur, who is defined by his strolling through the city, has been central to work by scholars of urban aesthetics like Walter Benjamin and psychogeographers.

In the past decade or so, more systematic attention has been given to urban aesthetics. For instance, scholars working in environmental aesthetics or everyday aesthetics became interested in urban landscapes.

The shift from the geometric painting-focused model to something more holistic is becoming increasingly apparent. In a 2019 essay “Our Everyday Aesthetic Evaluations of Architecture”, Abel Franco argues that we judge spaces as aesthetically pleasing. We judge, “whether and to which extent they appear to us as a means to realise and experience possibilities which are significant for us, where ‘significant for us’ means significant in relation to our unique and individual ideal of life.” This is very different from thinking about lines of symmetry and perspective.

It is important that the possibilities Franco mentions can be highly individual, particular to each person. One might be, for instance, “looking for the quality of the experience of reading Baudelaire in the café at this particular moment…” The aesthetic evaluation of any café then includes, for this person, asking whether it can afford this type of experience.

Another example Franco uses is that of judging an apartment as “uniquely placed within a particular network of spaces, that is, within a unique network of possibilities.” So the beauty of an apartment is not only its looks, but the way its location allows me to swing by a cool café on my way to work, or to jog by the river.

Some cities have striking painterly vistas that take our breath away. But more often than not it isn’t the skylines that capture us. We are exhilarated by the spaces and experiences of a city: its rhythm of life, the various choose-your-own-adventure stories it affords, and the fresh possibilities around every corner.

Tea Lobo is a Junior Fellow at the interdisciplinary institute Collegium Helveticum in Zurich, Switzerland. Her research focuses on the philosophy of the city and urban ecology. Her YouTube channel explores these issues with a broad, non-academic audience in mind. She has also managed a neighborhood development project in Basel, Switzerland. She can be reached at info@tealobo.com.

September 24, 2021 at 10:29 am

Any thoughts about whether, or the extent to which, there are differences in how one aesthetically experiences a geometrically planned, high-Modernist municipality (like, say, Brasilia) and how one aesthetically experiences an organically unplanned city (like, say, Bruges)? Wandering around someplace like Brasilia, you might get the sense that you’re interacting with an artifact created by a single author with a singular vision. Wandering around someplace like Bruges, you get the sense that you’re interacting with the crystallization of untold many decisions, made for an untold variety of reasons, across centuries, by the people who have lived there during those centuries. Does that affect how we experience, say, the spaces of each, the “means to realize and experience possibilities which are significant for us, where ‘significant for us’ means significant in relation to our unique and individual ideal of life?”

September 24, 2021 at 11:16 am

That’s a great point! Yes I’m sure the organically evolved windy roads of a medieval town afford a completely different kinaesthetic experience than the straight lines of a Modernist city. The latter enforces a rhythm of clear-cut purposes in going from A to B – and these purposes are pre-defined by the functional zones of the city. Whereas the former allows the slow discovery of possibilities and especially of those possibilities that might become significant for us.