What follows is a guest post by Eliya Cohen, PhD candidate in philosophy at Princeton University.

Imagine an industry that makes use of a business model much like a casino’s, except – in the most literal sense of the phrase – the house never loses. Not only would the house win in the long term, but every iteration of every game would be one where the house never coughs up a cent. And curiously, it would be precisely because the house never has to pay out, because patrons can never win, but only lose something of value, that the model would be largely unregulated.

Welcome to the video game industry, where the product is so enchanting that we almost forget that producers exploit us while we play.

People who worry about the ethics of games usually focus on what it means for the player to, say, shoot someone. What’s been relatively underappreciated is the way in which games enable producers – not just players – to act in morally questionable ways. And with the advent of new purchasing schemes called ‘microtransactions’, game producers are doing just this. They count on us becoming so enchanted by games that we act less rationally with our money.

Games make us vulnerable in this way. Producers charge us for our in-the-moment concerns and bank on our inability to anticipate how much we might want something. It’s like a cyclist who in the middle of a race is given the opportunity to buy a performance-enhancing drug. She’s so powerfully absorbed in the moment, that’s she’s susceptible to manipulation, to being led to do things she might not otherwise do, to buying things she might not otherwise buy. She is – in a sense – soberly intoxicated.

This is the kind of exploitation that’s going on at a large scale in the video game industry. And it’s the enchanting features of games, those aesthetic qualities, that help explain why games can be used to exploit us. Part of that story, part of what makes games so enchanting is that they’re deeply immersive, and deep immersion can make it more difficult to make fully rational decisions. We get so lost in the moment, focused so intensely on the directive in front of us, that our temporary desires can crowd out potentially more important ones, like a high school quarterback who in the middle of a big game can’t seem to notice or care about his concussion.

At the heart of the recent video game controversy is the question of how – and when – it’s okay to charge players money. Consumers used to walk into stores and buy physical copies of games. But now games are monetized as services rather than tangible goods: That first payment acts more like an entrance fee, while the rest of the game is broken up into bits and pieces behind store fronts – like a festival or fair.

Some of the most controversial of these payment options are in-game microtransactions, schemes that enable users to spend small amounts of real money on virtual goods in the middle of gameplay. You can buy anything from merely cosmetic items (e.g. attire for your character, decorations for their weapons) to gameplay enhancements (e.g. more powerful guns). And with the emergence of these payment schemes, the industry has seen a massive backlash from the gaming community.

Some paint video game producers as masters of exploitation. They ensnare users in games without disclosing the presence of controversial features to then feed on user’s vulnerabilities: the compulsive spending habits, the willingness to pay for success, the inability to prevent producers from exploiting the loopholes provided by emerging technologies and antiquated regulations.

Others defend microtransactions as not only innocuous, but necessary, with the consumer’s interest in mind: producers can monetize games without increasing upfront costs, gamers can pick their price point once they have a better sense of the product, and everyone can enjoy the benefits of extended replay value.

So why are these practices so objectionable to gamers? After all, they don’t really seem so bad in the abstract. Only some lack enough transparency, especially since the recent expansion of content ratings. Even fewer look like gambling or perpetuate gambling addictions. What could be so objectionable about a transaction when the producer is as transparent as she can be and the consumer seems pretty capable of walking away from the offer?

Part of the issue is that these transactions don’t look like classic cases of exploitation. Exploitation is when you make someone work for two dollars a day. Exploitation is when you charge exorbitant fees for necessities. If microtransactions are exploitative, they’re not exploitative like that. No one is holding a gun to our heads. No one is gouging money from us. On the contrary: aren’t we given more options, more freedom? I decide once I’ve had the chance to play the game if I want to pay more to enhance my experience. So how and to what extent are these transactions still exploitative?

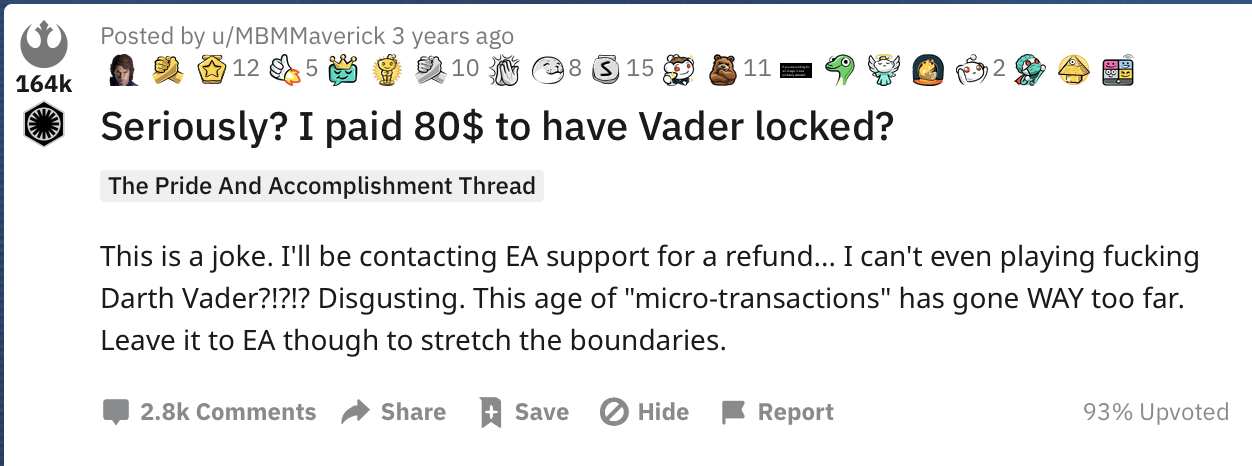

Outsiders don’t really find these practices shady, but any gamer can tell you their favorite example of monetization malpractice. At the top of the list: Star Wars: Battlefront II, 2017. Electronic Arts (EA) had made it difficult for players to make significant progress in the game without spending money, but in a way that gave them a mere probabilistic shot at getting what they wanted. Competitive online matches were largely won by paying customers and basic gameplay was made tedious to encourage purchases of important characters and weapons. It was like paying to enter a race, only to find out in the middle of it that you have to pay more to get roadblocks removed, and repeatedly being interrupted to do so. Just to give you a sense for exactly how tedious the “free” options were: the average player would have to spend 4500 hours of grinding (performing repetitive, often dull tasks) to unlock all extra content without paying. That’s the equivalent of working a full-time job for over two years! The game, mind you, was already $60.

The backlash against this game was enormous: commentators complained en masse that EA was gouging money from consumers for content that was promised to them in the first place, encouraging children to engage with features that looked like unregulated gambling, and doing so in ways that manipulated players to pay.

These problems are far from unique. It’s normal to exaggerate in-game visuals to encourage spending: flashing lights, colorful confetti, overflowing treasure chests. Other practices are more subtle.

A notable case came in 2017, when Activision patented a special matching algorithm – an algorithm that pairs players in multiplayer games – for Call of Duty: WWII. Normally, pairing happens randomly or by skill – think online games of Chess or Go. Activision’s algorithm paired non-paying players with high-skilled, paying ones to lure the former into making purchases to even the playing field. The game was basically designed to ensure failure for those who didn’t pay.

The core complaint is that producers take unfair advantage of us. I want to show how the context of gameplay, the enchanting interactive and immersive effects of games, plays a role in limiting rationality and enabling exploitation.

Video games are immersive and interactive in a highly distinctive way, a way that many other immersive and interactive activities are not.

When you’re immersed in an experience, when you’re deeply absorbed, it’s as if parts of the real world are shrouded in a haze. You might not notice that someone has entered the room or that the laundry chime has gone off. You might not realize you have an injury and need rest. You might forget to eat or sleep. Important concerns are set to the side.

Games are so immersive that they’re capable of both reducing the perception of pain and loneliness in hospital patients but can also lead to death and hospitalization in gamers who have forgotten to take care of their basic needs.

But unlike most movies or books, which are also immersive, video games can be immersive in a much stronger sense. And that’s partly because they’re also exceptionally interactive. They don’t just give us experiences; they give us directives and the ability to carry them out. Yes, game creators authorize players to partly determine features of the game: I click these buttons and my character flees from the enemy. But that’s not all. Within the fiction, I’m apparently identical to the character I control. I’m not just Ellie anymore; I’m Jin Sakai, 13th century Samurai. My thoughts and choices just are Jin’s thoughts and choices. My desires, abilities, motivations, what I live for, are his. When Jin dies, I ipso facto die as well. I occupy him; or rather, he – in a sense – occupies me.

When you’re watching a movie, you can lose yourself in it. It can be as if you’re a passive subject with no capacity to act. You, the viewer, don’t really exist in the world you’re absorbed in. It’s immersive, but often not especially interactive.

When you’re playing a video game, your identity as an agent is front and center. It just might not align entirely with your identity outside the game. You can be that Samurai in 13th century Japan, or a WWII veteran solving crimes as a rookie detective in Los Angeles, an animated cup trying to fight his way through a gambling debt to the devil. Now, through the innovation of VR, you can experience what it was like to be on the Apollo 11 flight to the moon or what it’s like to be a sea creature in the San Francisco Bay.

While movies are immersive but not as interactive as video games, tabletop role-playing games like D&D are interactive but not nearly as immersive. When you play a video game, the images on the screen, the sounds, the physical feedback from the controls enhance your imaginative experience. Because many of your important perceptual faculties are already engaged by the game, because the game fills in parts of the world for you, you don’t need to rely so heavily on your own imagination. The result is more vivid. The game provides real stimuli that augment and complement imagination to provide a more lucid overall experience.

Movies don’t engage our agential capacities and tabletop role-playing games require effortful imagination. The result is that they’re less immersive than video games.

Because of how immersive and interactive games are, we as players are vulnerable to certain practical irrationalities, in at least two ways: (1) it can be more difficult to act rationally when immersed in a video game and (2) it can be more difficult to reason upfront about desires you don’t yet have. And producers monetize these vulnerabilities.

Because of how absorbing games can be, they can have rationality limiting effects on us; they can make us bad at thinking through decisions – kind of like we were drunk – or they can make our preferences realign in a way that makes it momentarily rational to spend money, even when we would reject the desire in a cooler moment. The intensity makes the objective feel real even if the stakes aren’t.

When I’m immersed in playing CoD: WWII, I have an intense desire to win. The game has given me a temporary directive: kill the enemy. At that moment, I don’t care about paying my rent. Ellie the graduate student is just a faint image in the background. I’m Ellie, American Ally, and I have Germans to kill. I’ll do anything for my team; so charge me for that stronger weapon!

After the game ends, I might wonder what I was thinking. I could never have imagined spending money on something so pointless. Why didn’t I just play a different game? And isn’t there something simply slimy about someone who takes advantage of your state of mind in a moment like this?

It’s like a sex worker who in the middle of sex with a client pauses to renegotiate the price or offer “premium” services for an increased fee.

One maor difference between the cases, however, is that the client already had the desire for sex. Video games imbue you with desires; they give you the imaginative stage on which to act, the role for which to play. They set your mind on a goal and hand you the tools to accomplish it – for a price.

Because games invite players to take on new roles and entertain new desires – desires that are rational in the world of the game – other, potentially more important desires can get crowded out. Even when these desires are powerful in the moment, they’re often fleeting. Games are designed to make it easy for us to set aside things we might want or believe on reflection or at times when we aren’t playing. Even if we are aware in the moment of what we want for ourselves in the real world, it might conflict with those we have in the middle of play. The alternative goals and motivations are so vivid – so imaginatively present – that we sometimes prioritize them. And this creates contexts where producers can exploit consumers, who can charge us for what is momentarily salient.

Games can also be so interactive, that they kind of change us; and it’s more difficult to reason about desires or perspectives we don’t yet have and more difficult anticipate how much we might want something before that change.

Think more broadly about experiences that change us, like for example, becoming a parent. It isn’t just difficult to communicate what it’s like to have children to me – I don’t have them. I can’t really anticipate what it’ll be like, what I’ll be like. I can’t as easily – in the ordinary way – reason for the person I will become, since I can’t vividly appreciate what it will be like to be her. Philosopher L.A. Paul has called this a “transformative experience”.

When we play games, we often empathetically occupy roles that are out of step with our position in the real world, and that can have similar rationality limiting effects on us. Take an especially vivid case of this: Researchers at Stanford developed a game – Becoming Homeless – to study the effects of virtual reality (VR) games on empathy. Participants interact with their game environment to attempt to prevent eviction, protect their belongings, and stay alive while on the street. The goal was to combat the misconception that homelessness is a result of who you are and the choices you make. The results were clear: VR experiences have longer lasting effects on belief and empathy – participants were much more willing to donate money to help the homeless – than from the influence of other sources like reading stories or watching movies. People came out of the VR experiment changed.

Games can change us. Sometimes just while we play – when we’re fighting Mongols in 13th century Japan – sometimes in a more lasting way – as with the VR experience. And no one can really tell us how invested we’ll be, how vividly we’ll feel the evil in an enemy’s action, how much social or competitive significance a game will have. Games sort of transform who we are, even if just for a moment.

So: if a monetization strategy relies on the fact that I can’t anticipate the person I will become in the game – or if that’s too strong – the position I empathetically occupy, the desires or beliefs I will have in that moment, that is taking advantage of a vulnerability.

Maybe microtransactions should be better regulated, and more control should be relinquished to the consumer: more opt-out mechanisms, card limits, parental controls. Some of this already exists, but maybe not enough. Maybe producers should take purchases out of the game. Make us go to the store to buy separate content discs or download separate add-on games so we aren’t purchasing while we play.

Maybe they’re not morally dubious enough to warrant more regulation. But that doesn’t mean we can’t cast moral disapproval on it. Something objectionable is still going on. It doesn’t matter if it becomes normalized, if we all end up tolerating it – as most of us do with YouTube advertisements or data mining on Facebook. Something dubious is happening in those cases, even if it isn’t impermissible or illegal. Perhaps it’s just shady, just a mere moral mistake.

Video games are enchanting, beautiful things; and enchanting, beautiful things can make it harder for us to think straight. Producers know this and take advantage of it. This doesn’t mean microtransactions should be outlawed. Nonetheless, gamers are right to be resentful.

Notes on the Contributor

Eliya Cohen is a PhD candidate at Princeton University working primarily in the philosophy of games, metaphysics, and philosophical logic.

February 16, 2021 at 10:02 pm

I’ve seen streamers drop hundreds of dollars playing Genshin Impact to unlock a 5-star character with their preferred aesthetic. It’s tough to imagine anyone buying a more expensive version of the game with that content already included. Why buy a $500 game when there are such great, affordable alternatives?