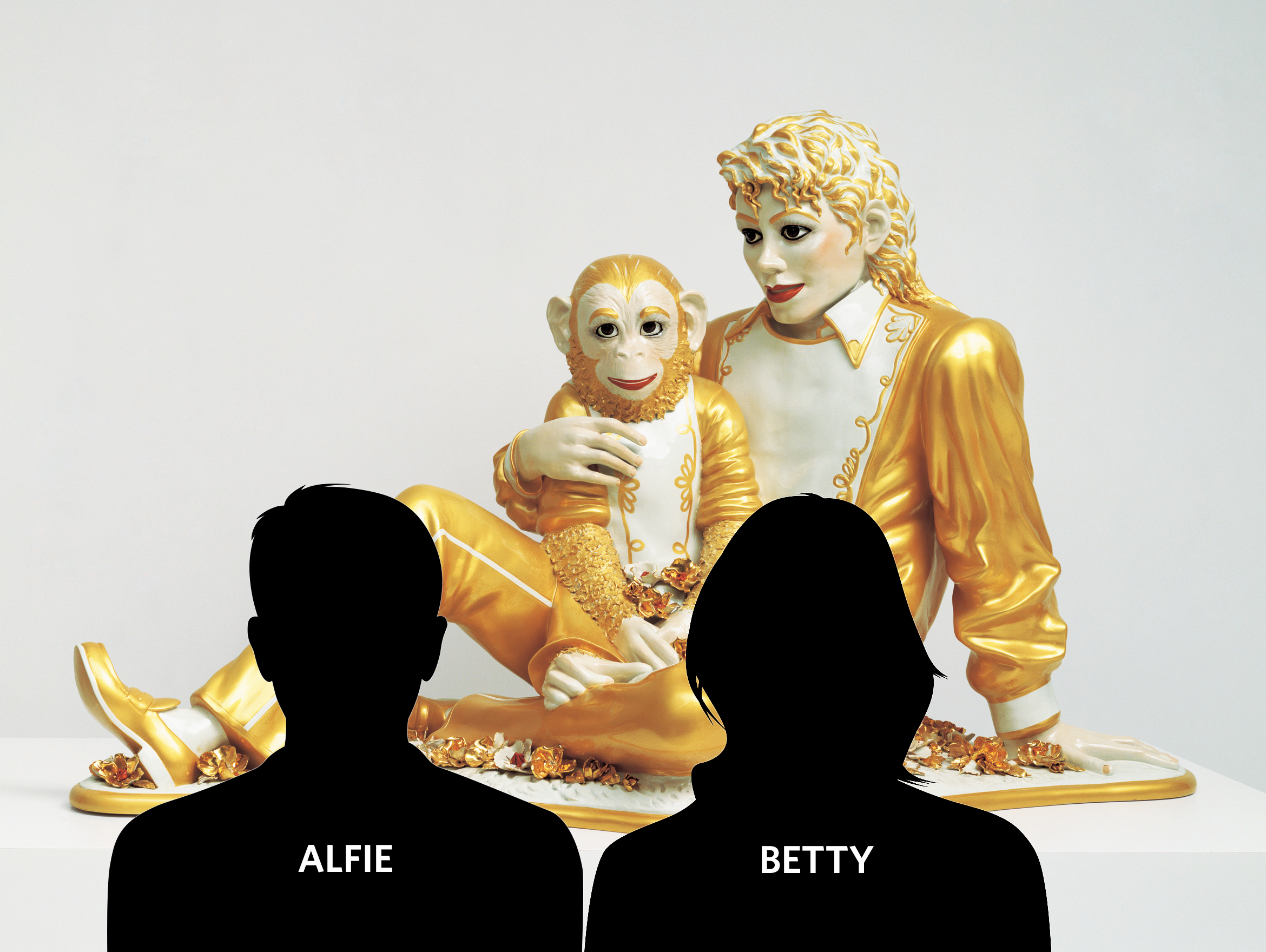

ALFIE and BETTY observe Jeff Koons’ Michael Jackson and Bubbles (1988)

What follows is a guest post by Shen-yi Liao, Aaron Meskin, and Joshua Knobe. They offer an overview and summary of the ideas in their new paper, “Dual Character Art Concepts,” just out in Pacific Philosophical Quarterly. (Non-paywalled version available here.)

Alfie: This sculpture is not art. I know many people think it is art, but when you think about what art really is, you will realize that it is not art at all.

Betty: Of course this is art. It is in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art!

Alfie: I know. But all the same, it’s not a true work of art. It’s impersonal factory-produced rubbish.

Betty: Wait, I agree that this sculpture is completely awful in every way, but still, it’s obviously a piece of art.

What we see in this little dialogue is a conflict between two very different views about what it even means to call something art. Betty thinks there is some straightforward sense in which just about any sculpture that is displayed in a museum is a work of art. Alfie disagrees. He seems to think that nothing can truly count as art unless it reflects certain sorts of values.

This sort of conflict reveals, we believe, something very fundamental about the nature of people’s very concept of art. In some important sense, people seem to have two different criteria for determining whether or not something is art. One of these criteria is pretty straightforward and descriptive (like the one Betty uses), while the other seems to involve something deeper about the values embodied in the work itself (like the one Alfie uses).

So then, what exactly is going on here? Why do people have these two very different criteria for applying what might seem to be the very same concept?

In a new paper, we suggest that it might be possible to get some insight into these disagreements by turning to recent work in cognitive science. Cognitive science research has explored a whole class of different concepts called dual character concepts that seem to be associated with two different criteria. If we take a look at what is going on with those concepts more generally, maybe we can get a better understanding of people’s ordinary notion of art.

For a paradigm example of a dual character concept, consider the concept scientist. We can easily imagine a dialogue about whether a person is a scientist that looks a whole lot like the dialogue above about whether a piece is a work of art.

Alfie: That person is not a scientist. I know that many people think she is a scientist, but if you think about what it really is to be a scientist, you will realize that she is not a scientist at all.

Betty: Of course she is a scientist. She is a professor in the physics department!

Alfie: I know that. But all the same, she is not a true scientist. She never changes her views when she sees new data; she just keeps holding on to her preconceived dogmas.

Betty: Wait, I agree that she is an awful scientist in every way, but still, she is obviously a scientist.

Our core hypothesis is that what is going on in this conflict about what it means to be a scientist is exactly the same as what is going on in the conflict described above about what it means to be a work of art. In other words, our hypothesis is that the concept of art is a dual character concept.

To test out this hypothesis, we compared the concept of art to a variety of other concepts. Previous work suggests that some concepts are dual character concepts (e.g., the concept friend), while others are not dual character concepts (e.g., the concept stroller). We ran a series of experiments to see whether people treat the concept of art in the same way that they treat other dual character concepts.

For example, one trademark property of dual character concepts is that you can use them in sentences like this:

There is a sense in which she is clearly a friend, but ultimately, when you think about what it really means to be a friend, you would have to say that she is not a friend at all.

Those sorts of sentences don’t seem to make any sense when used with concepts that are not dual character concepts. For example:

There is a sense in which that is clearly a stroller, but ultimately, when you think about what it really means to be a stroller, you would have to say that it is not a stroller at all.

Okay then, the key question is what happens when we try to use that sort of sentence with the concept of art.

There is a sense in which that is clearly art, but ultimately, when you think about what it really means to be art, you would have to say that it is not art at all.

The results showed that people think that this sentence sounds quite natural. So, at least in that respect, they seem to be treating the concept of art in just the same way they treat other dual character concepts.

If this hypothesis does turn out to be right, it could help to shed a lot of light on otherwise mysterious aspects of our concept of art. After all, we could then take all the discoveries cognitive scientists have made about other dual character concepts (scientist, friend, etc.) and apply them to the concept of art as well. And as we suggest in the paper, the concept of art is not the only artistic concept that seems to behave this way. In fact, figuring out which art concepts are dual character or not may have downstream implications for other conversations about art, such as whether today’s artists can still sell out.

Those curious to hear more can read the full paper here.

Notes on the Contributors

Shen-yi Liao is interested in the interactions between minds and social realities. This broad interest gets him to explore connections between imagination, cognition, values, art, and more. These explorations are even more fun when he get to do it with others like Aaron and Josh.

Aaron Meskin is head of the Department of Philosophy at the University of Georgia. He works on aesthetics, philosophical psychology, and the philosophy of food.

Joshua Knobe works on questions at the intersection of philosophy and cognitive science. Most of his work involves going after the sorts of questions usually associated with philosophy using the sorts of methods usually associated with cognitive science.