Visual Artist Rachel Hecker interviewed by Alex King

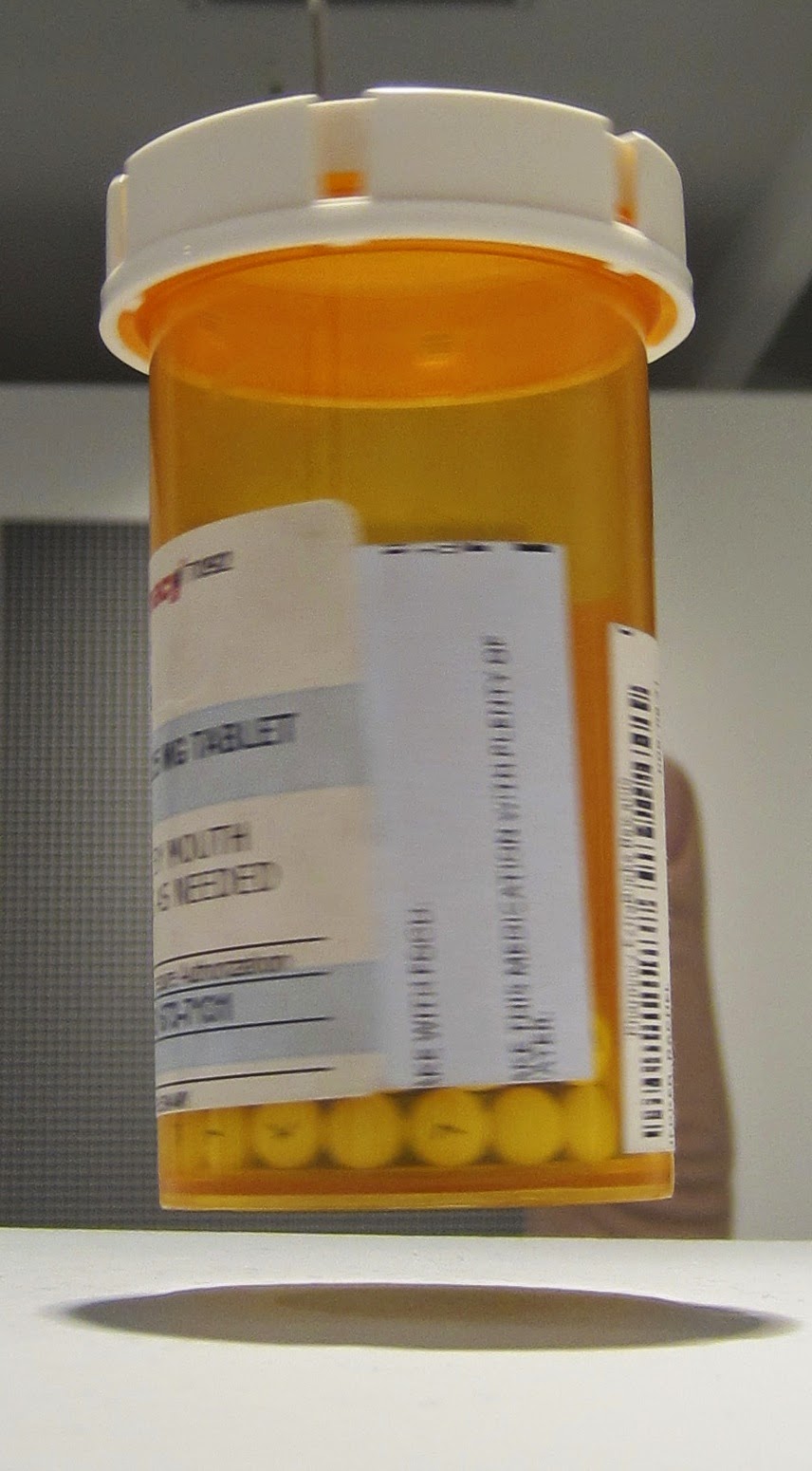

Rachel Hecker is a visual artist and an Associate Professor of painting at the University of Houston School of Art. Her conceptually based projects, from contemporary portraits of Jesus to levitating bottles of Xanax, have been included in numerous group and solo exhibitions in museums, galleries, and alternative spaces throughout the US. She’s received many awards, among them Art League Houston’s 2013 Texas Artist of the Year.

Your work has a lot of visual affinities with Pop Art, especially with figures like Andy Warhol or Claes Oldenburg, but your aims seem very different. What do you see as the most important differences between their aims and yours?

My art lineage is definitely Pop Art. I was taken to museums as a child, and I remember seeing Warhol’s Campbell’s soup cans at a young age, and for the first time was able to associate art with things that were relevant to my life, and part of life’s vernacular.

Pop Art emerged as a reaction to Abstract Expressionism, and in this way it was as much focused on the art world of the 50’s and 60’s as anything else. It challenged hierarchies and rattled the watchtower, freeing up ideas of content and production, and contained an inborn irreverence that I really appreciate. It democratized art in certain ways, but it also idealized subject matter. I am much more interested in temporality.

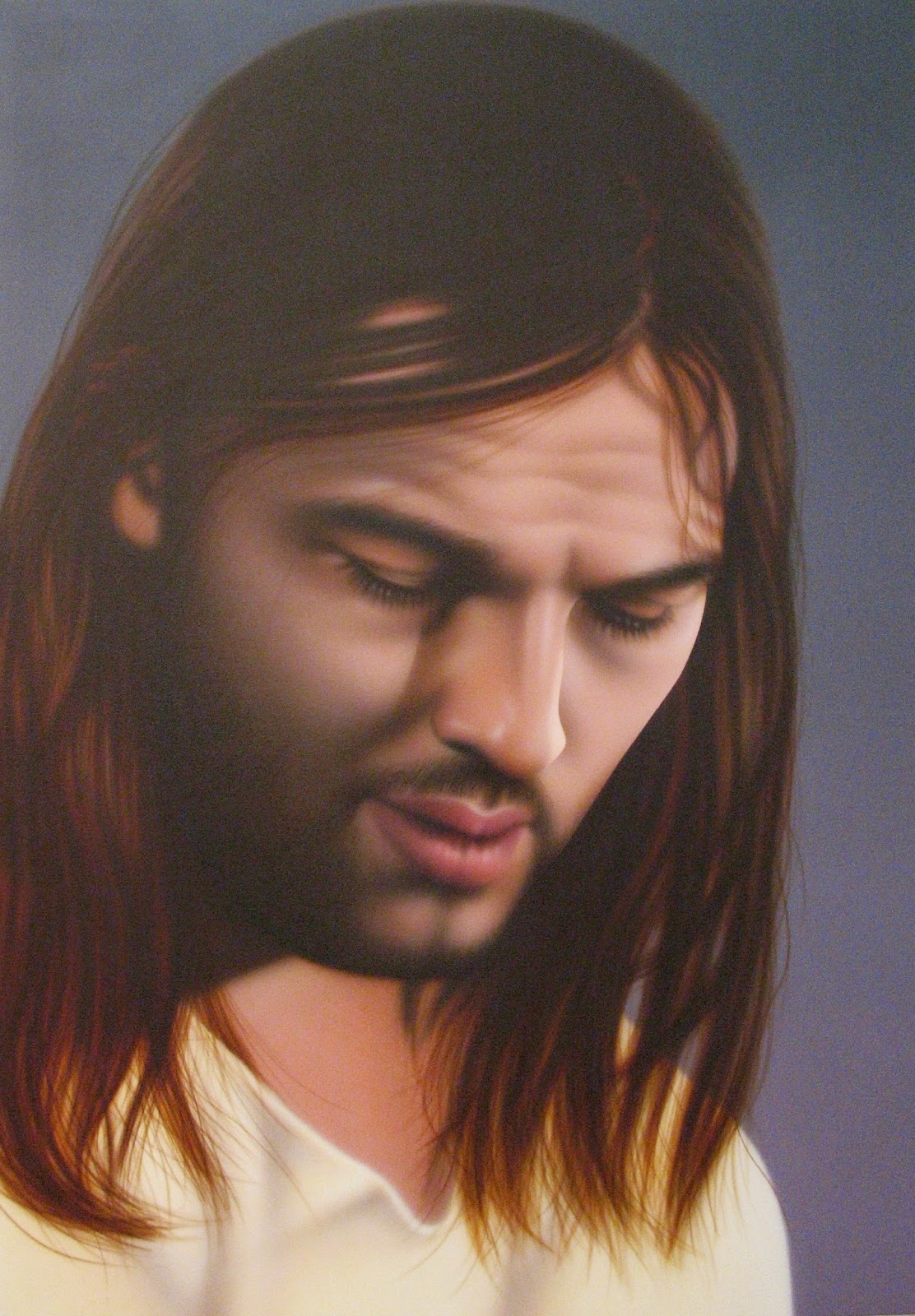

Much of my work is located in the mundane fields of popular and material culture, where I think we live (socially and culturally). I use the languages of pop art as a form of dialect to construct a critique of those fields, or at least to poke at them. In this way, I veer from the neutrality of Pop Art and towards something that is embedded with questions. With the Jesus paintings, for example, I tried to imagine what a contemporary western devotional painting of Jesus might look like, so I culled images from the fashion, music and film industries. My feeling is that western devotion is located in these secular fields, and if we were to recognize Jesus at all it could only be through those filters. This builds critique into the proposition.

Jesus #2, David Gilmour (2011, acrylic on canvas, 48″ x 34″)

The distinction between painting and sculpture can look pretty arbitrary sometimes. Paintings exist in three dimensions, rough paint and canvases jut out from flat surfaces, and so on. You are constantly exploring and questioning this distinction. At the end of the day, do you think there’s something important that nonetheless separates the two forms, or do you prefer to think of it as a merely notational difference?

I recognize the authority of painting, its rich history and unbroken currency, its status as commodity, and often riff off of that as a kind of sidebar. Sculpture isn’t as polite as painting. It requires kinesthetic engagement and encroaches space. It has to be approached and reckoned with in different ways than painting. There are constraints and strengths implicit to each. I see them as available strategies.

Floating Zanax (2013, pill bottle, magnet, electromagnet, wood, 44″ x 11″ x 11″)

While we’re on this topic, I want to ask about your “paintings that do something” series and your kinetic art. Do you think of them as a further step in blurring the boundary between painting and sculpture, or just a way of making more apparent the physicality and motion that’s already present in all painting?

Paint dries, and it locks in moments of being with a thing. What’s left is a sequence of movements over time, fossilized and frozen. Painting records motion and physicality, and asserts it’s own physicality as an object. But a painting is essentially inert – its motion belongs to memory and a corresponding nostalgia. I get uncomfortable with that nostalgia, and worry endlessly about paintings’ inertness.

I always want more from a painting, or from my paintings. I want painting to defy its own inertia. I recognize this wish as being completely nutty, but it is there. I painted a portrait of my brother and it took me several months to get it right, and when I finished it I sat back and thought that it needed to be “enlivened” in some way, and the next day I implanted false eyelashes in the portrait as a way to “save” it. That didn’t help much. But the impulse to give painting an agency that it innately can’t possess is a constant concern. That led me to optical work like the variation of the Hermann Grid where there is palpable phenomena, or anamorphic images, or the QR code painting where the image is imbedded with another image that is only decipherable on a smart phone. The kinetic work and the Jesus paintings are an extension of this desire for agency.

QR Code Painting, from series Paintings that Do Something (2010, acrylic on canvas, 60″ x 60″) – download free QR code reader app for smartphone to view this painting

In other venues, you’ve talked about how you make your art as an “open-eyed meditation,” and said that “slow painting is like turning beads on a rosary.” Your paintings obviously take incredible technical skill. Why is it important that your art be created in this way, rather than by a team or mechanically reproduced? What do you think the relationship is, in general, between art and technical skill?

There is something poignant about trying to make something perfectly, and knowing that failure is implicit. Everything that I do in the studio focuses me on the process of making, and while I am with the work, my attention can’t waver far. I don’t find that there are many things that require that kind of intensity, and with it that sense of presence. In this way I associate my studio practice to meditation – a state of intense alertness. I could make the text work more expeditiously and more perfectly with vinyl stencils, but I don’t think that it would have heart, and I would forfeit my time with it, which is not something that I am willing to surrender. Skill, attention to craft, and caring for a thing are qualities that give back to the maker. I wonder what is gained if this is lost.

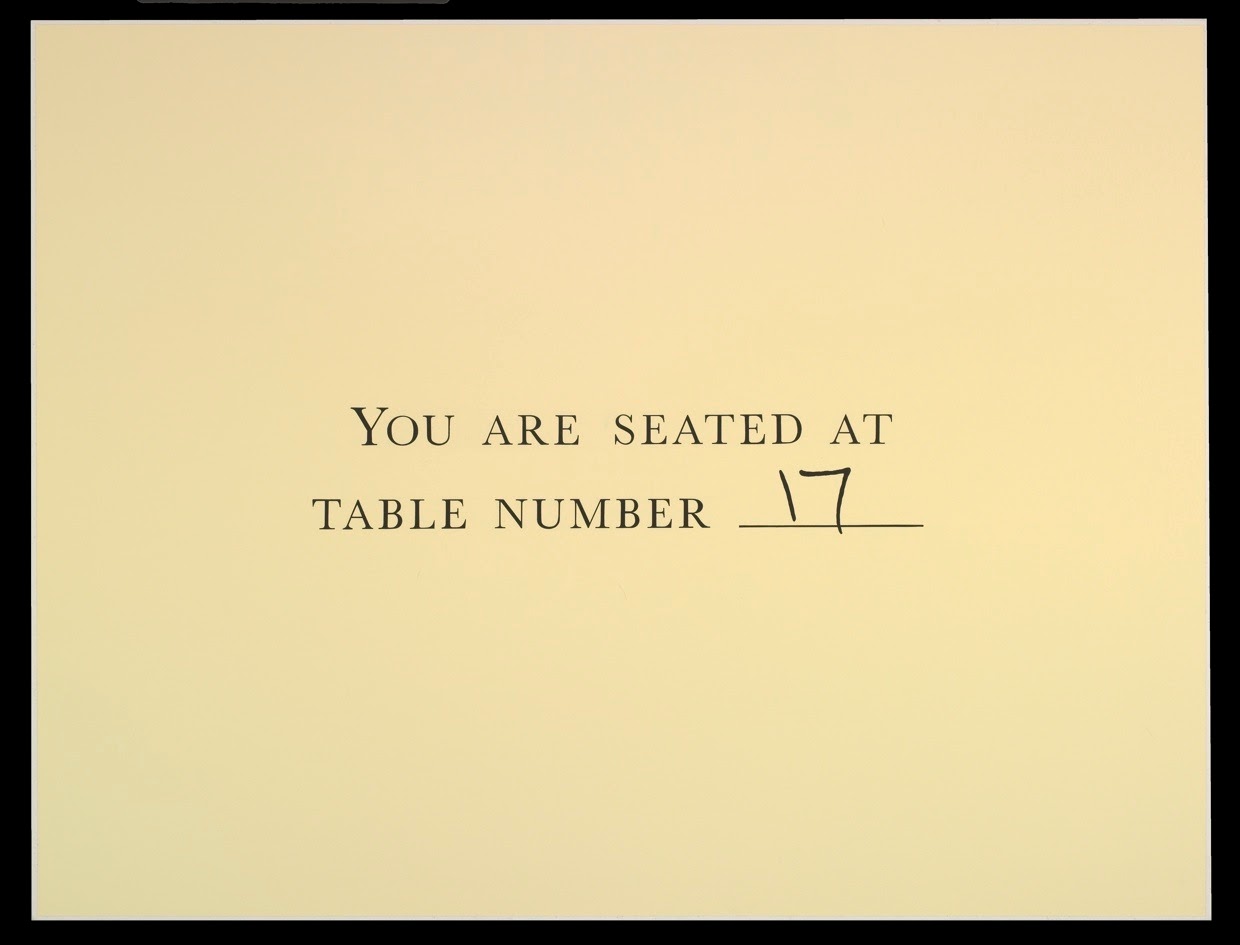

Table #17 (2009, acrylic on canvas, 32″ x 42″)

Do you think these are qualities that give something to the audience as well?

If someone carefully looks at the work they will notice foible, and that is a foundational condition of being human. In the graphic work, for example, no two “E’s” are ever painted the same way, despite my effort. It is in these fissures that I think we recognize our interconnectedness. The representational work is photo based, but I use photography to slow-down the reading of an image by remaking it with paint. This is antithetical to the way many painters use photography, which is often to expedite image making and reception. I think that there is something counter-intuitively and counter-culturally useful to slowing down the reading of any image, and to slowing down generally. This is one of paintings foundational strengths.

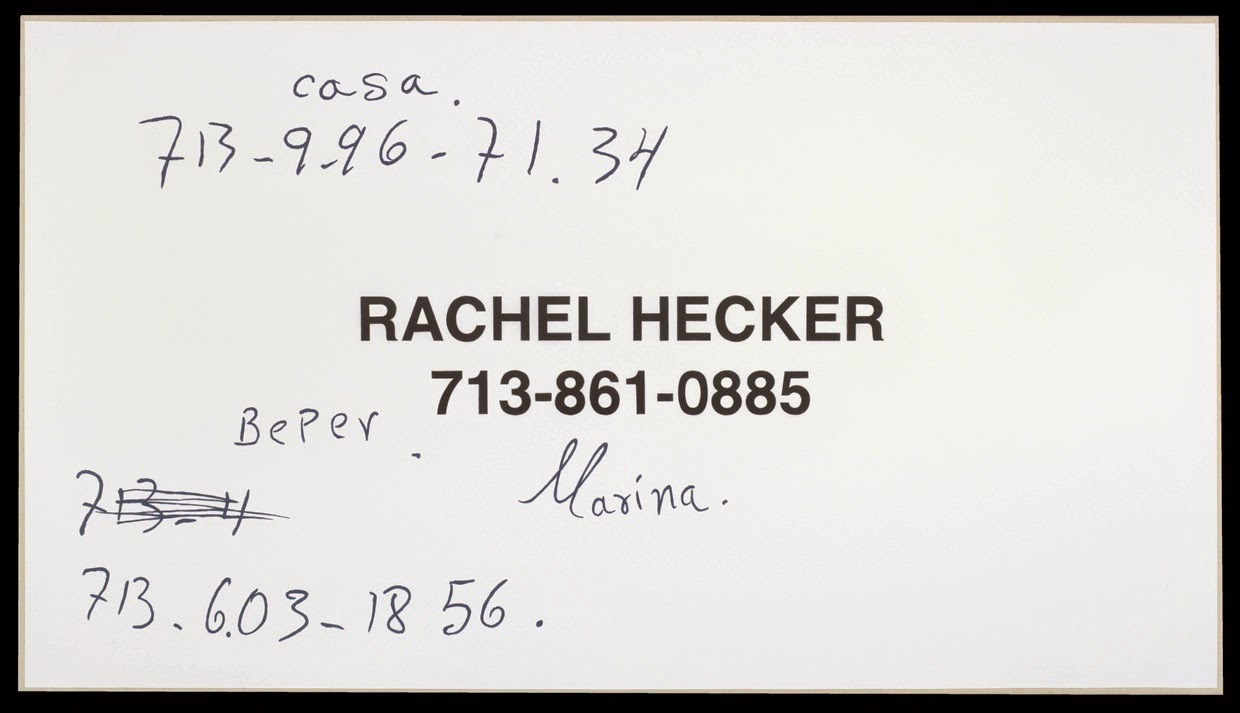

You’ve also said that you reproduce paper detritus to achieve unselfconsciousness and unintentionality. There is something paradoxical, though, in the attempt to avoid self-conscious choice of subject matter: you’re still picking certain papers over others, picking papers rather than other castoffs, etc. To what extent do you think you’ve succeeded in achieving unselfconsciousness? To what extent do you think such a thing is possible?

I am incapable of making a gestural mark, and for the most part it is impossible for me to intentionally make any visual thing that lacks self-consciousness. When I first really noticed my grocery shopping lists, I recognized that they contained unselfconsciousness as content and as form. They didn’t have any reason to be in the world except as transactional objects – things that mediated between thought and action. In this way, they innately lacked visual awareness – it wasn’t a condition of their form. As I collected the lists and notes, I noticed that they also contained a kind of poetry, and forensic evidence of how I lived in the world, and seemed more candid than anything else that I could offer. And yes, I did make selections of what to paint and what not to paint, and those decisions were based on diversity. I wanted them to be the same but different from each other. The collection was diverse because I have the propensity to write on scraps of things and odds and ends, and I wanted the work to reflect that.

Marina business card (2006, acrylic on canvas, 26″ x 46″)

And one final big-picture question: Why do you think artistic unselfconsciousness is a valuable thing to aim for?

To be self-conscious is to be “ill at ease”. It suggests a constant weighing and measuring, and is at best an anxious and reactive relationship to people, places, things and circumstances. Unselfconsciousness is aspirational, and I think only experienced when ideas of past and future are suspended. In those moments there is a kind of lockstep with time, and very little reason for violence to self or to the world or others. That I identified this condition only in my grocery shopping lists is a good indication of my level of attainment, but it’s good to have goals!

Detail of Finger Statue (2013, coated EPS foam and acrylic, 65″ x 17″ x 15″), with Pixel Skull in background (2010, acrylic on canvas, 78″ x 60″)