What follows is a guest post by John Rapko. John is a Bay Area-based philosopher of art and art critic. Currently he teaches art history at the College of Marin and ethics and the philosophy of art at the California College of the Arts. He previously taught the philosophy of art and the theory of contemporary art at UC Berkeley, Stanford, and the San Francisco Art Institute. He has published academic writing in the Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, British Journal of Aesthetics, and Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews, and art criticism in Artweek and artcritical.com. A volume of his lectures on the philosophy of contemporary art, Achievement, Failure, Aspiration: Three Attempts to Understand Contemporary Art was recently published by the Universidad de los Andes Press.

In late March of 2008 the San Francisco Art Institute’s Walter McBean Gallery mounted a show of the artist Adel Abdessemed’s work, entitled “Don’t Trust Me.” Within days the show became the object of a storm of protests, the particular target of which were six videos, each just seconds in length, that depicted animals seemingly being bludgeoned to death with single blows of a sledgehammer to the head. The protests, in the form of emails to various administrators and staff at SFAI and of on-line comments, were of such vehemence as to induce SFAI to close the show within a week of its opening, and some two months before its scheduled end.

Or so it is said. Yet little about the work, and nothing of its significance, has been settled through discussion, and not only because of the brevity of the exhibition. The SFAI administration at that time put out numerous claims about the circumstances of the making of the work that were incredible on the face of it, and have since been explicitly contradicted by Abdessemed himself. Nor has anyone ever produced evidence of a single credible threat of violence towards anyone associated with the exhibition. The show seems more a rumor than an actual exhibition, with half a chorus objecting to show on the grounds of the evident depravity of the killing animals for, or perhaps as, art; the other half considers the objectors to be a herd of yahoos, part naifs, part terrorists.

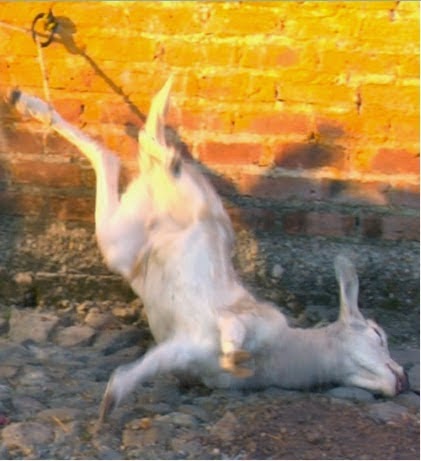

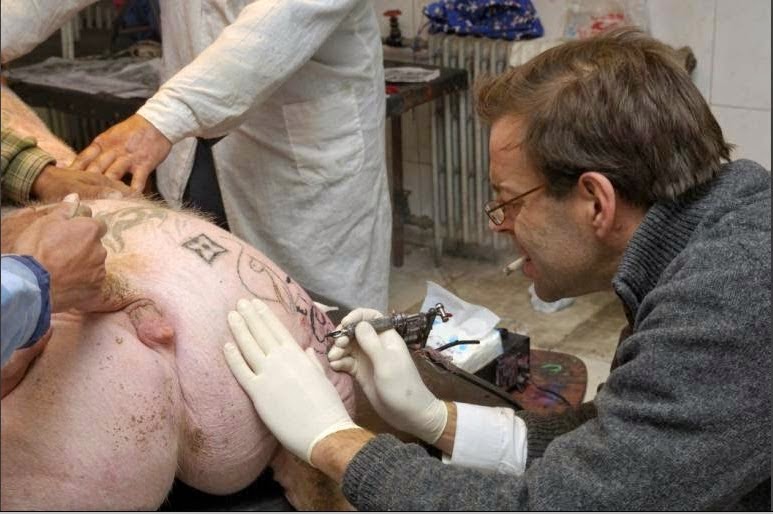

The issues clustering around the use of animals as materials in contemporary art have been raised again in the recent show at SFAI, “Wrong’s What I Do Best.” The show, co-curated by Hesse McGraw and Aaron Spangler, allegedly presents the work of artists who bear some sort of resemblance to the country music ‘outlaws’ whose work is inseparable from their hard-livin’ lives, and yet whose work, in its very waywardness, somehow simultaneously obscures those very artistic lives from which it emerges. One wishes that the works shown were merely as murky as the concept. Aside from a characteristically challenging video from Kara Walker, almost hidden away under the stairs, most of the works are dispiriting, with a new kind of low reached by the ‘paintings’ from Club Paint, whose sole aim seems to be to catch and hold the viewer’s attention precisely so long as it takes to induce a mood of boredom tinged with disgust. The show’s announcement attempts to catch the eye with a photograph of a taxidermied pig, its back marked with a skein of tattoos. It’s a work, if that’s the word, by the Belgian artist Wim Delvoye, who began tattooing live pigs in the 1990’s and who, allegedly in evasion of Belgium’s animal-protection statutes, in 2004 set up an ‘art farm’ of tattooed pigs in China. After being tattooed, the pigs, so Delvoye claims, are allowed to live some of their ‘natural’ lives. At some point, determined by who knows what criteria, the animals are killed, then either taxidermied or skinned; in the latter case, the skins are then stretched and displayed. These works, along with Abdessemed’s films of animals being slaughtered, and yet others of his showing animals confined in a tiny space and set to fight each other, and a recent one showing chickens afire, their legs bound and hanging from a wall, have been grouped together in discussions of the use and abuse of animals in art.

The discussion of such works as Abdessemed’s and Delvoye’s can hardly be said to have advanced much in the past six years, but the general defense of such works characteristically involves one or both of two claims: (1) It is said that the works are ‘about’ something of evident social, political, or cultural importance (‘post-colonialism’ or ‘industrialisation of food’ in the case of “Don’t Trust Me”, ‘Arab Spring’ with regard to the video of the burning chickens). In most cases it is further claimed that the works are ‘critical’ of what is being depicted and/or of the practice of which the action depicted is an aspect; (2) The defenders of these works charge those who object with a lack of self-awareness and self–reflection. If those who object eat animals or animal products, they are said to fail to grasp how these works indict them for their complicity in larger practices of exploiting animals. If the objectors are moral vegans, they are said to lack the acuity to see that and how these works actually expose the very practices they oppose. So those who object to the works are said to be intellectually blinkered in their failure to grasp the work’s subject, and artistically obtuse in not sensing the work’s ‘criticality’. The claims in (2) diagnose the character traits that block those who object from grasping the claims made in (1).

Both these defenses are located at a very general level, and fail to consider, in a manner typical of contemporary theorizing in the visual arts, some basic questions of meaning and value in art, and how these come to be attached to artworks: How and under what conditions, one wonders, does being ‘about’ some important issue relieve an artwork of the charge of immorality? What criteria govern ascriptions of ‘criticality’? If I show an episode of “My Mother the Car,” dub it an artwork, and declare it to be a critical examination of ‘the imbrication of industrialization and domesticity’, does it thereby possess that very meaning and significance? With regard to these particular problematic works, little has been published. A seemingly sophisticated attempt by Pamela M. Lee to interpret Abdessemed’s films as ‘about’ transhumanism (don’t ask) goes awry from the beginning when she misdescribes the films as showing human hands—there are none.

But it seems to me that neither these two lines of attempted defense of these works, nor my testy counter-questions, really approach what unsettles people so. For the unease here, I would suggest, is not alleviated by the assurances (false in these cases, but conceivably true in other works involving animals) that the animals were humanely treated (Delvoye’s pigs), or that the practice of slaughter is merely being documented (Abdessemed). How might we approach the issues? Is there anything in the widespread response that the very idea of using animals in art is problematic, even for those who eat meat and wear leather?

One line of reflection that suggests itself asks us to reflect on what an artist does in making a work, and what the significance is, in the mind of the viewer, of the very fact that the work is made to be viewed. In the opening chapter of his great book Painting as an Art, the philosopher Richard Wollheim describes how what the painter does in the course of practicing painting as an art; the account might well be thought valid, with some qualifications, for the visual arts generally. The painter paints and monitors with her eyes the results of her activity. So in the act of painting, the painter actually plays two conceptually distinct roles: the agent/maker, and the viewer. The painter qua maker marks something for the painter qua spectator. The painter, Wollheim stresses, is the first viewer of the painter, though of course not typically the last. And so the viewer of a painting, whether the painter herself in the act of painting, or a later viewer of the completed work, has a particular intimacy with the painter qua maker; the maker has made it for the viewer, and the viewer takes up what the painter has done, gazes upon it, explores it, imaginatively enters it, reflects on it, with each of these affecting and being affected by the others. In a different context of considering the use of animals as food, the philosopher Tzachi Zamir has noted that something made to be perceived has a what he calls an ethical depth-structure, that of a temporally extended action: the action inaugurated by the making of something is only completed in the appreciative viewing of the thing. So in the arts, the appreciative viewer necessarily experiences a kind of complicity, or again an intimacy, with the action of the artist to a greater degree and a greater intensity than in a wide range of other uses of artifacts. The viewer consummates what the artist begins: this is the very action, the making of something to be seen, put to such an astounding range of good uses in the millennia of human life, that is at the core of the idea of the visual arts. And when the inauguration of the work is morally problematic, the viewer shares in the maker’s fault; the making and the viewing are two parts of the same wrong. Zamir adds that this has an additional dimension of wrongness: not only completing the morally problematic act, but participating in, and so sustaining, a wrong practice.

If something along the lines of Wollheim’s and Zamir’s suggestion is right, we can see at least what would be so intensely objectionable about these works for the moral vegan: they ask not merely that one use the animal, and not just one enjoy the product of the use, but that one complete the use. For the moral vegan, for whom all use of animals is abuse or exploitation, this multiplies the original harm. But does the moral vegetarian, and moreover the meat eater, have any special cause for complaint, beyond whatever artistic badness, narrowly construed as a work’s possessing the everyday artistic faults of being incompetent, boring, or trivial?

The philosophy Christy Mag Uidhir has investigated our responses to racial matching and mismatching of actor and character in films. Why, he asks, might we think that there is something artistically flawed in John Wayne playing Genghis Khan, but something artistically valuable in Linda Hunt playing a male dwarf in The Year of Living Dangerously? Mag Uidhir argues with great care for the conclusion that racial mismatching is a flaw when it encourages false beliefs about the character and/or the character’s perceived ethnicity. He briefly discusses the case of animal abuse in saying that we find Robert Bresson’s Au Hasard, Balthasar “less beautiful” when we learn that the donkey Balthasar was actually beaten as part of the making of the film. This seems off the mark to me, but the more general claim Mag Uidhir makes is helpful: as with racial mismatching, the use of animals is artistically objectionable (that is, aside from concerns whether the animal was in fact harmed in the making of the work) when it blocks the viewer’s ‘up-take’, one’s ability to engage with the work appreciatively, entering the open-ended process of play among cognitive, moral, imaginative, and participatory perspectives. In malign instances of uses of animals in art, we are constantly interrupted in such play by the awareness of the very thing, the animal, that was used in the process. We may be blocked not by the thought that the animal was harmed, but by the sheer thought that the animal was used. For such use is in an important sense unnecessary: there is no existing practice of, say, tattooing pigs in which Delvoye was participating, and so in the very viewing of the work we are asked to enjoy, and then to develop a taste for, works that involve an unnecessary use of animals. Artistic as well as moral creativity would be better channeled to other ways of artistic making, ways that could be reflectively affirmed.

Even if something along the line of thinking suggested here is right, this could only be the beginning of engaging with these complex issues. But there’s an irony in the show “Wrong’s What I Do Best” that escapes the curators. One wonders whether the curators did after all sense something of this depth-structure, and seek to exploit it for a further problematic effect. There are two of Delvoye’s pigs in the show, placed a few feet from each other in the gallery’s mezzanine. One cannot see them until one arrives near the top of the stairs. Both pigs’s heads are slightly cocked, the further one more so, so that one sees without preparation the pigs as if turning towards you as you arrive. The effect is of the briefest sort, as a kind of dullness and lack of focus afflicts the pigs’ eyes, and one is struck rather by their alienness and peculiar lifelessness, more dead than the dead. The cheapness and half-heartedness of the effect seem like nothing so much as the emblem of the show, as the show’s announcement suggests, but not in a way that does credit to the curators.

References

Pamela M. Lee, “Animal Feeling” (2012) in Adel Abdessemed je suis innocent.

Christy Mag Uidhir, “Aesthetics of Actor-Character Race Matching in Film Fictions” (2012). Philosophers’ Imprint 12/3

— “What’s So Bad About Blackface?” (2013) in Race, Film, & Philosophy, eds. Dan Flory & Mary Bloodsworth-Lugo

Richard Wollheim, Painting as an Art (1987)

Tzachi Zamir, Ethics and the Beast (2007)